Faraway Horses (21 page)

Authors: Buck Brannaman,William Reynolds

When people ask me to lay a horse down the way they saw it done in the movie, I decline. Laying down is not a circus sideshow act. It’s a valuable tool for helping horses with troubled lives.

It would have been nice if there had been time in the movie to explain that laying Pilgrim down was done to save his life, but as I’ve said,

The Horse Whisperer

wasn’t about teaching people how to work with horses. It was a love

story. My own story is about horses, and I guess it’s a love story, too. I do the things I do when I work with horses because I just plain love them.

I thought my part was over once the movie was made, but I was wrong. I had to go to New York for the press junket, an event put on by the studio to preview the movie for film critics and the press. The folks at Disney wanted me to be the person from the film to comment on the livestock work—the press wanted to meet a real “horse whisperer.”

The movie’s publicist, Kathy Orloff, promised she would be there to run interference. She had helped me understand the business of making a movie, filling some gaps in my knowledge. She’s a pro from the word go, so I felt much better.

The call to go to New York came right after I finished a clinic near Mammoth, California, so the timing worked. My folks and I had been to New York once, when Smokie and I were guests on the TV show

What’s My Line,

with Arlene Francis and Soupy Sales, but that had been a long time ago.

Bill Reynolds and I stayed at the Four Seasons Hotel, a pretty high-dollar deal where rooms came with remote-controlled drapes (I didn’t have curtains until I was thirty). Those drapes were the nicest I’d ever seen, even though I thought they needed hemming. They were kind of bunched up on the floor, but Bill said they were supposed to stay that way. He said they called it “puddling.” I still don’t know how

he knew that. I thought that’s what a cowdog does when you’re too hung over to let him out of the bunkhouse.

My first morning there, I pointed the remote and opened the drapes from twenty feet away. Then I put on my hand-painted cowboy tie with a solid-gold tie bar, a hand-tailored charo-style bolero coat, and a new custom-made felt hat.

The press event was held at another hotel, so Bill and I together with a girl from Disney were escorted to a limousine. It was drizzling rain, and the doormen in front of the hotel held umbrellas over us. I politely said to one of them, “Sir, I appreciate your concern for my headwear, but if a little rain is going to ruin it, it isn’t much of a hat.” When I realized everyone else was getting the same treatment, I smiled and got into the car.

A press junket is basically a round-robin. You sit in a small room and meet one at a time with folks from the “working press,” as they are called (I kept wondering where the nonworking press fit into the deal). One after another they came into my little room and interviewed me on videotape. The stars of the film, including Bob Redford, Kristin Scott Thomas, Sam Neill, and Scarlett Johansson were getting the same treatment in their own little rooms. Keeping us separate was a good way to get all the interviews done at the same time.

Reporters from TV and radio, newspapers and magazines came in, popped a cassette into the video camera, and after a technician got the lights set, they’d ask me questions for

ten minutes or so. Then off they’d go to the next little room. Each of them demanded his or her own special lighting. It didn’t matter whether they were from a small local TV station or from one of the bigger outlets, they all saw themselves as stars in their own right and seemed to like the opportunity to shout orders at a cameraman or lighting technician.

I’m a cowboy from Wyoming—a title I’m actually rather proud of—and now that I was in the big city, some of the studio people were a little uneasy about how I was going to handle the interviews. This old rube knew that reporters can be like bulldogs and give you a hard time. That’s why I find truth to be the best approach. The press finds it refreshing, and you don’t have to remember what you’ve said.

The first news lady in the room told me she had once been a news anchor at one of the local TV stations. She no longer was, but she maintained the attitude that probably got her the anchor job. Seeing that I was a cowboy, she gave me a condescending look, glanced at her watch, checked her schedule, and said, “I certainly hope this isn’t your first interview.”

I replied, “Ma’am, I sure hope it isn’t yours either.” And then I said, “I talked more into a microphone by the time I was twenty-five than you will in your entire life. What’s your first question?”

By the time her ten minutes were over, the reporter had changed her tune. She liked hearing about the horses, and at that point the studio executives and producers, who were

listening to the interview, were satisfied I was going to be able to handle anybody who came along.

Next on my schedule were a couple of young women from MTV and

Rolling Stone

magazine. One of them asked, “What about those poor horses in Central Park? Don’t you think it’s just awful how they have to pull those heavy carriages around all day?”

I had an answer for that question. “No, I don’t,” I said, then explained that the Central Park horses are content. Pulling carriages on rubber-rimmed wheels on paved streets is a low-stress job, and the horses are calm and relaxed, not anxiously laying their ears back or wringing their tails. Plus, these horses get lots of attention and affection from passersby. And horses love attention and affection as much as we do.

The horses that people should be concerned about are the neglected ones that, after the “newness” of ownership wears off, live in box stalls all day. These horses have no purpose, no jobs to do. All they do is eat and make manure. Even prisoners get to exercise more than these horses, and the horses have never done anything wrong. If they had the choice, these horses would choose to be carriage horses rather than stand in their stalls.

The press junket worked out fine. I met people who were genuinely interested in what it’s like to be a cowboy today and what it’s like to work with horses the way I do. I could tell they enjoyed doing interviews about something that was realistic, and it was a fine experience for everyone.

* * *

Even people who have read the book and seen the movie ask me, Exactly what is a “horse whisperer” anyway? I define the term as a horseman or horsewoman who has the ability to communicate with a horse in a way the average person has little or no way of understanding. Through experience and study, these men and women learn how really sensitive a horse is and how sensitive they need to be to accomplish things with horses.

Ultimately, they learn how little effort is needed. Someone who doesn’t know anything about the ways of a horse could be fooled into thinking the approach is all cosmic or mystical. It’s not. Anybody can do it who has a passion to do it and has put in enough time. These people are horsemen and horsewomen, not whisperers.

The real benefit of

The Horse Whisperer

is that it helped the audience understand another way of thinking about horses. It’s a good way, and if people want to see it as something mystical, that’s fine. I like to think that the work Nick Evans and Robert Redford produced helped a lot of horses and a lot of people, and I’d be proud to ride with them again, anytime.

I

HAD BEEN HURT A FEW TIMES

playing volleyball and basketball as a kid, and over the years I’d come off a few horses. The result was bulging discs in my back. Many active men have the same kind of problem by the time they’re forty, and they learn to live with back pain. In 1998 I’d had bad sciatica, but I got over it. The pain was kind of gone, and I thought that was the end of it. What I didn’t realize was that I still had those bulging discs.

In 1999, I was in Maine starting a two-year-old colt. He was kind of touchy, and when I saddled him he bucked pretty hard. Three or four hours later he was still bucking hard. I got on him the next day, and we got along fairly well. He didn’t buck, and I had him walking, trotting, and loping, as well as turning and accepting me swinging a rope on him.

Just as I was about ready to get off, I got a little too close to the round corral fence. The toe of my left boot hung up

on a rail, which stretched my leg out behind me. It also drove the heel of my left boot into the colt’s flank. He wasn’t so solid that he could handle that kind of stress, and he immediately started bucking. With my legs stuck out behind me, I couldn’t make much of a bronc ride. The colt bucked me off over his head and into the fence, and I opened a fair-size gash in my scalp.

Furthermore, while I was down, the colt bucked over the top of me and stepped on my back, which broke a couple of my ribs. He also stepped on my hip and my ankle. He missed me with only one foot out of his four.

I hurt pretty bad, and I was a little concerned that a rib had been driven through a lung. But I could breathe all right, and even though I was in pain, I went ahead and finished the clinic.

A couple of days later I went to the hospital in Portland, Maine, to have X rays taken; my lower back was sore, and I wanted to make sure I didn’t have a collapsed lung. The doctors didn’t seem too concerned about my back, and with my lungs all right, I went back to work, broken ribs, pain, and all.

I tried to be careful getting on and off colts for the next couple of weeks. The pain was indescribable, but people had been planning all year on going to my clinics, and I wasn’t going to let them down.

I was in North Carolina a few weeks later, doing the third day of a three-day clinic. I was just finishing up, having already loped maybe ten miles that morning on my first two

colts, and I was on my way to get on my last one. The sun was out, the autumn leaves were still on the trees, and as I was walking down to the round corral, I told myself, “You know, I’m feeling about as good as I’ve felt in a long time.” Indeed, I was almost pain-free.

Over the next hour and a half I loped circles in the round corral, explaining what I was doing to the crowd, when the motion of my hips must have hit just the right angle. I felt a little pinch in my back and a kind of tingling feeling down my right leg. I thought that was odd, but I kept on riding.

A couple of minutes later I thought that I had blown my right stirrup. When I looked down and saw that my foot was still in the stirrup, I knew that I was in trouble. A few more seconds, and I couldn’t feel my right leg at all.

I stopped the horse, stepped off, and collapsed to the ground. I couldn’t support myself. I couldn’t lift my right foot, and the only way I could get my right leg to move forward was by grabbing my pants leg and swinging it.

The arrogance of youth led me to believe I was suffering from only a pinched nerve in my back. After a few days it wouldn’t be a problem, I was sure; the swelling would go down, and I’d get over it.

The next day I got on a plane and took off for Colorado where I was scheduled to do a clinic at a guest ranch called the C Lazy U near Boulder. When I changed planes in Cincinnati, I found walking very difficult. Worse than that, I had no sense of where my foot was. I always felt sorry for people whose gaits had been altered because they were crippled

up for some reason, and now I really understood what they went through. As I grabbed my pants, lifted my leg, and flopped my right foot forward, people stared at me. I felt like a freak.

So, there I was, trying to get to my plane and with a couple of bags to carry. At every step, I had to stop and lift my leg. I was making my way in this fashion along a marble corridor when I fell flat on my face. Fortunately, a man on an electric cart came by, picked me up, and drove me to the gate.

Mary met me at the Denver airport and helped me into the truck. As we drove out to the C Lazy U, I held a bag of ice I had gotten at the airport against my back. Mary looked over with concern, and when it came right down to it, I was worried, too.

When I started the clinic the following day, I thought sitting in a director’s chair could get me by. I made it through the day, but by that night the pain was so bad that friends of mine who were riding in the clinic persuaded me to cancel. They were nurses, and they advised me to get an MRI. It was the first time in my career that I had ever canceled a clinic.

Mary drove me down to Boulder where I saw a neurologist. He gave me the MRI, which revealed two herniated discs in my back. I had no idea at the time what that meant. The doctor explained that nerve damage to my spine might possibly cause permanent damage to the motor function of my right foot. Surgery was going to be the only chance to

relieve the pain and possibly get back some movement in my leg.

I couldn’t have been more shocked. I tried to keep a stiff upper lip, but then it hit me that all the things I’d loved out of life might be over: to play with my child, to teach her how to play basketball or run with her or maybe even ride a horse again. I hobbled out of the doctor’s office ahead of Mary, dragged my way to the truck, and cried like I was a little baby again.

I had the surgery, hoping I’d wake up and my foot would work right away. That wasn’t the deal. At first nothing much had changed. I was damn sore from the operation, but my foot still didn’t work.

They let me out of the hospital after a couple of days, and Mary and I hung around Boulder for a while until I was strong enough to travel. I walked with a cane and dragged my right leg along. My left leg worked fine, but my right leg didn’t. Although I wanted to start physical therapy, the doctors asked me to hold off for a while.

I was depressed for a week after we went home. All the strength I’d always shown my family was gone now. Mary was taking care of me, which was never meant to be; I was supposed to be taking care of her and the kids, and I felt like a burden.

Mary drove me to physical therapy where I’d try to lift weights, but the therapy didn’t do the muscles down around my foot any good. They weren’t getting the message from the nerve. Some muscles higher up in the leg worked, and

after months of intense weight lifting and other exercises I reached the point where I could at least walk in a reasonable manner. But the muscles that operate the tendons going down over my ankle still didn’t work.

And they still don’t. I have no motor function of my lower right leg. I wear a brace under my boot, and the boot has a zipper so I can get my brace in.

I’ve always been positive, and I haven’t given up. I don’t know if you can will a nerve to heal. Over the short term, I can assure you that you can’t. Over the long term, I’ll get back to you on that.

They say nerves heal real slowly. Lots of things about us heal real slowly. I have time. I’m still a relatively young man, and I’m hopeful that I’ll get a lot of that function back. But if I don’t—hey, I’m riding horses again and giving clinics. Nothing holds me up in my teaching or traveling: I continue to put on tens of thousands of miles each year. Sure, I’m not a hundred percent, but then again I may have never been a hundred percent, anyway.

We’re all kind of back to our lives. Right now, I’m sitting in a hotel room in Lexington, Kentucky, getting ready to have dinner with the man who’s in charge of the starters at racetracks all over America. He wants me to help him find a way to get race horses in and out of the starting gates so that everyone is a little safer and gets along a little better. He also wants me to help the people who work at the tracks have a little more understanding about how to work with horses.

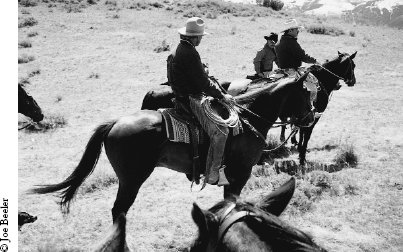

Buck riding on the Flying C Ranch in Nye, Montana. Every spring, Buck and a group of “hearty” westerners gather at different ranches for a branding put on by Buck’s friend Chas Weldon. Buck is in the foreground with Chas facing

(near right)

and Bill Reynolds

(far right).

So, while I’m still trying to work at fixing myself, I’m back fixing other problems in the horse world. I can feed my family, and my family’s together and they’re doing well and thriving. I can’t complain a bit. I’m still blessed.

The stories in this book come from what I’ve learned traveling around the country working with people and their horses, as well as just living life. I hope that some of the stories have made you laugh and some have made you think. Some even may have made you cry. All of that is real healthy.

I hope God blesses all of you the way he’s blessed me. He’s blessed me with my family and good friends, with the people I’ve met, with the horses I’ve ridden, and with the lessons I’ve learned. Sometime you may see a cowboy in a truck pulling a horse trailer wave at you going down the road. Just wave back, would you? It’s probably me.

I continue to soak on things—think about them—and ponder the events that have shaped my life. Hopefully my life’s far from over, and maybe someday we can sit together and I can share some little bits of information that will help you in your search for whatever it is you’re looking for. And maybe you can share with me. I hope you find meaning in your life, whatever it is.

In life, we don’t know why things happen. I believe God is not responsible for the bad things that happen to you. Sometimes I think He’s responsible for the good things, but sometimes it’s something you shape up for yourself.

I wish you every success that you deserve. Not just if you ride horses, but in all aspects of your life. That’s the best I can wish for you. For me, my life’s journey has been laid out in front of me. The road may bend out of sight at times, but I know what lies ahead: the faraway horses.