Faraway Horses (16 page)

Authors: Buck Brannaman,William Reynolds

Some horses are so easy to work with that we refer to them as “born broke.” These horses are open to just about anything we want to do with them. However, others aren’t real inclined to get along with us. Some of them are so afraid of losing their lives that they are very difficult to work with. Either way, the responsibility lies with us. As horsemen, we have the ability to adjust to the needs of the horse as well as to his individual personality. We have what it takes to get along with him. Some people find a very troubled horse too much to deal with; selling him might be the best thing they could do.

Occasionally you will find a horse born with very limited possibilities. These are no different than children who are born retarded. Sometimes, a foal will get the placenta over his nose, become starved for oxygen, and then suffer brain damage before the mare can pull the placenta off. Or a horse is born with some sort of birth defect that makes it difficult or impossible to perform normally. With such horses, you try to do the best you can, and if they fall short of becoming great horses, you accept them for what they are and make the best of it. Horses can be only as good as they can be. The best thing you can do is wait until you know any horse before you begin to have expectations. Before

that, you need a general knowledge of horses. And then you do the best you can with what you have to work with.

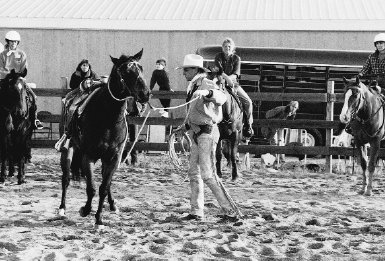

Some horses progress faster than others. Buck is able to lope this horse in the round pen on a loose rein.

Punishing a troubled horse for what you determine to be bad behavior is punishing him for something that in

your

mind is wrong. But it isn’t wrong in his mind. He’s only trying to do what he believes he needs to do at the time. As a horseman, you should have the wisdom to see how the horse prepares himself and to understand what he has in mind.

Then, if what he has in mind isn’t what you’re looking for, you head him off. You redirect him. You change his mind. You change the subject, and you keep on changing it until after a while the negative behavior disappears.

I don’t believe in waiting for a horse to do the wrong thing and then punishing him after the fact. You can’t just say no to a horse. You have to redirect a negative behavior with a positive one, something that works for both of you. It’s as though you’re saying, “Instead of doing that, we can do this together.”

When things start to go wrong with a child, there is nothing wrong with laying down some rules, with being strict and saying no. You can talk to a child, reason with him, but you still need to give him a choice. You need to give him someplace else to go in his mind, and something else to do so that he can succeed.

If you don’t, if you wait for him to do the wrong thing because you weren’t paying attention to your responsibilities and then you become angry and beat on him, he won’t learn anything from what he did. He’ll learn to fear you. He’ll learn to be sneaky and covert about what he does. He may never learn to do the right thing. Instead, he is likely to learn nothing but how to fail.

Now, I’m not saying that everything is milk toast, fuzzy, and warm when you are working with a child or working with a horse. But at the point you become angry or you abandon your sense of reason and logic and become ruled by resentment and anger, by spite and greed and hate and all the other negative feelings that seem to run the world these days, you aren’t going to be any more successful with your horse than you would be with your child.

Unlike a child, a horse makes it pretty convenient for you to live your life this way. You can say all kinds of things about him, and he is never going to step up to the microphone and say, “Hey, world, let me tell you about this human. Let me tell you what he’s made of.” But a horse will still make his feelings known, and if you have mistreated him because of your inadequacies, his behavior will tell on you. You may meet someone like me who will tell you what the truth of his behavior means. You may not enjoy hearing it, but the truth doesn’t go away.

You can tell a lot about an owner’s character by observing the behavior of the horse. Some people come to a clinic to become a little safer on their horses because they’re scared or worried. Maybe their horses are scared and worried, too. Overcoming such problems is easy to accomplish over a period of days. I can help people become more confident and understand their horses a little better.

Quite often I’ve had people come to my clinics who are too passive. They don’t assert themselves in ways that evoke respect from other people or from their horses. Because these owners behave like victims, their horses may have bitten them or responded in other disrespectful ways that reflect an owner’s overly passive nature.

Many such people come to my clinics because, consciously or not, they’re searching for a sense of strength that they haven’t found elsewhere. A woman may have been pushed around or bullied by her husband or her kids as well

as by her horse. Learning a little bit of horsemanship—learning how to take charge, set a goal with the horse, and then achieve it—can be a very liberating experience. It can have a positive influence and permeate the rest of her life.

Women often acquire a new perspective toward their lives and a new self-confidence during my clinics. They reassess their lives and relationships, and they often “clean house” when their husbands or boyfriends don’t measure up or adapt to their new approach to life.

Other people are overly aggressive. I’ve had men who are too embarrassed to treat their horses in public the way they treat them at home. But their horses won’t cover for them. Whatever the owner is like with the horse at home becomes apparent at the clinic, because the horse will behave in a way that reflects the treatment he’s used to receiving. That’s what I mean when I talk about a horse’s honesty. And thank goodness they are that way—they would be difficult animals to work with if they were liars on top of being so athletic.

Many times people have told me that what they’ve learned from me about understanding their horses has helped them begin to understand themselves a little bit better and then allowed them to make changes that improved their lives far better than they could have ever imagined.

One such person was a chariot racer who lived near Big Horn, Wyoming. Chariot racing is a winter sport, and it has a following in some parts of the West. It’s a lot like what

Charlton Heston did in the movie

Ben Hur,

except the chariots aren’t usually quite as fancy and the horses that pull them tend to be about half broke. Some of the horses have never even been taught to drive. The racers harness them up, beat them over the rump, and away they go over frozen ground or through snowfields.

When the man from near Big Horn tried to harness a horse and teach it to drive, they got into a fight. The man lost his temper and beat the horse with a two-by-four until the horse was unconscious. Somebody called a veterinarian, but it was too late. The horse was still unconscious. He wasn’t dead, but there wasn’t anything the vet could do, so he had to put the horse to sleep.

Someone called the sheriff, and the man ended up in front of a Sheridan County judge. The charge was animal abuse, and the vet, a Dr. Wilson, was one of the witnesses against him. After the judge heard the case, he asked the vet what he thought an appropriate punishment might be. The vet suggested ordering the man to pay to take one of his other young horses to one of my clinics. He t--hought that teaching the man how to properly start a colt might help him learn something about understanding horses, an education that would be more effective than simply hitting him with a big fine. The judge agreed.

I hadn’t yet moved to Wyoming from Montana, but I’d been giving clinics in the Sheridan area for a while, and the person who organized my clinic there told me about the chariot racer’s offense and the judge’s sentence.

On the one hand, I wanted to hate the man for what he had done to my friend, the horse. But after considering the situation, I realized that the man most likely expected me to hate him. He had probably hardened himself to what was coming, and he was mentally prepared to get through whatever hostility he might experience.

When the man showed up at the clinic, I treated him no different than any other student. Giving him the benefit of the doubt, I acted as though he’d done nothing wrong. The locals knew, of course. There was a lot of whispering about who he was and the horrible thing that he had done, so you can imagine the shame and regret the man must have felt.

I was the only person there who treated him well, and after a day or two he started to make progress. He started asking questions, and by the time the clinic was over, he and his colt were doing pretty well.

After everybody else had said their good-byes, the man stood off by himself near the corrals. I was loading my trailer when he came over. He was a big man, over six feet tall, and weighing about 225 pounds. He just stood there for a while.

I waited until he spoke. “I don’t know what to say,” he began. “This weekend has changed my life, and in more ways than you will ever know.” With that he started to cry.

I gave him a hug. “I may never see you again,” I told him, “but I hope what you’ve learned helps carry you through times when it’s hard to control your emotions. I hope you

find the wisdom you need to fix some of the things that aren’t okay in your life.”

He nodded, then shook my hand. “Well, thanks for giving me a start.”

Dr. Wilson was a wise man. So was the judge. Making that defendant attend one of my clinics turned out to be as good a punishment as could have been dished out. He went through a few life-altering days, which also validated something for me, too. My initial inclination had been to be mean and vengeful because of what the man had done to the horse. Yet if I had, if I had approached him as an enemy, I wouldn’t have accomplished anything. There would have been no chance for him to learn a better way.

To have been able to play even a small part in helping someone change his life simply because he’s been to a Buck Brannaman clinic is a very humbling experience. I’m grateful for the opportunity. It is a real blessing, and when people lean on me for emotional and psychological support, I take the responsibility seriously. I do the best I can to help them along because we’re all trying to figure out how to live our lives, how to get by, and how to answer a few simple questions. We’re all involved in the same search. Horses, like people, should be treated how you want them to be, not how they are.

There are so many variables in a clinic that I can’t control: where the horses are coming from; whether they’re scared, upset, or otherwise bothered. Nor do I have control

over where the students are coming from or whether or not they’re going to be able to help the horses when they need help. I can tell students what they need to do, but I can’t do it for them, and there’s always an underlying worry that someone will get hurt or even killed (I can laugh now about Polack and the water jug, but it wasn’t very funny at the time). A person can fall off a horse as easily as he can fall out of the back of a pickup truck or even stumble on the way to the bathroom and bump his head on the sink.

We all know that there’s a chance you can lose your life doing some of these things. But a person’s dying at one of my clinics, even if only due to sheer accident—the sort of thing that can happen to anybody, anywhere, anytime—could negate every bit of good I’ve ever done, no matter how many people I’ve helped or how many horses I’ve saved from the slaughterhouse. It doesn’t seem fair, but it could happen. I always live in fear of something like that, and I just have to leave it up to the good Lord to help my students and me through.

In a clinic in Boulder, Colorado, I had about twenty people in the colt class. All but one of them were doing their groundwork, helping their horses get comfortable and readying them to be approached and handled. The man who wasn’t doing the work owned a little paint colt that he’d tried to have started before. He had hired a local horse trainer who had failed. The colt was afraid of the trainer, and she was afraid of him.

Once Buck gets a saddle on a young clinic horse he goes through all the same actions he had previously done with the horse unsaddled. This is to reinforce that the horse has nothing to fear after the saddle is cinched up.