Falcon (8 page)

killed

Aikneich

, the peregrine falcon, would die before the year ended – this had happened recently, he explained, after a man had shot a peregrine mistaking it for a chicken hawk. ‘That year, before leaving’, he continued, ‘the Aikneich flew around look- ing at all the towns and houses here and there, and sitting on the houses as if to inspect them.’

14

The association of falcons with souls and the notion that fal- cons facilitate communion with heaven or the divine is evoked in numerous mystical traditions. In Sufi mysticism the exiled soul suffers while in mortal flesh and longs to return home to the cre- ator. To become pure enough to rejoin God, one must follow the difficult path of higher and higher levels of spiritual life. Such themes are richly evoked in the work of the great Iranian poet Hafez; in one poem he compares man to a falcon who flies from his home to the city of miseries. Christian writers, too, have used

A late 17th-century calligraphic prayer in the shape of

a falcon by Mohamed Fathiab.

falcons in tropes of mystical union. D’Arcussia wrote of how Holy Scripture compares the falcon to the contemplative man who does not embroil himself in worldly affairs and who, ‘if at any time there is need for him to descend among them, at once flies back to the sky’,

15

and explained that a saintly person is often portrayed through the image of the falcon. In

The Hound and the Hawk,

historian John Cummins elegantly glosses the ways in which St John of the Cross used the theme of the falcon binding to its prey in the skies as a metaphor for his soul’s union with God. The falcon’s stoop, Cummins writes, ‘has two senses: the peregrine’s hurtling descent which gives it the momentum to soar up almost vertically, and the individual’s self abasement and relinquishing of individuality which enable the soul to rejoin the divine’.

16The nearer I came to this lofty quarry,

the lower and more wretched and despairing I seemed.

I said: ‘No-one can reach it’; and I stooped so low, so low, that I soared so high, so high, that I grasped my prey.

17Mystical unions shade toward erotic unions in falcon tropes, as this medieval Spanish lyric shows:

To the flight of a heron,

the peregrine stooped from the sky, and, taking her on the wing,

was caught in a bramble bush.

High in the mountains

God, the peregrine came down to be closed in the womb

of Holy Mary.

The heron screamed so loudly that Ecce ancilla rose to the sky, and peregrine stooped to the lure and was caught in a bramble-bush.

The jesses were long by which he was caught: cut from those wobs

which Adam and Eve wove.

But the wild heron took so slowly a flight

that when God stooped from the sky He was caught in a bramble-bush.

18Lovemaking has frequently been metaphorized as the struggles of falcon and prey. In Turkish songs the love between a virgin bride and her fiancé is couched in terms of the helpless attempts of a female partridge to escape from a falcon. And falconry has irresistibly contributed to erotic falcon myths. Taming falcons and seducing women have long been under- stood as analogous arts. Many high-school students learn their first falconry from Shakespeare’s

The Taming of the Shrew

, where the gentle art of falconry is a trope embedded in the male arts of seduction. As John Cummins delicately phrases it, both activities involve a man’s obsessive wish to bend a free- ranging spirit to his own desires, and he quotes a medieval German maxim that ‘women and falcons are easily tamed: if you lure them the right way, they come to meet their man’.

19A wry take on gender relations in 1950s America.

The metaphor runs both ways: falconry has frequently been couched in erotic terms: novelist David Garnett, for example, described T. H. White’s attempts to train a goshawk as reading strangely like an eighteenth-century tale of seduction.

Furthermore, the trappings of falconry – its technologies of control such as hoods, jesses and leashes – working in conjunc- tion with a discourse that often portrays the falcon as mistress and falconer as slave, have allowed it to become figured in explicitly fetishistic and masochistic terms. ‘Falconers do it with leather’, proclaimed a 1980s car-sticker. The fabulously baroque and disturbing psychosexual thriller of the same decade,

The Peregrine

by William Bayer, is the

ne plus ultra

of such imagin- ings. A crazed falconer trains a giant peregrine to kill women; kidnaps a journalist, calls her ‘Pambird’, decks her in modified falconry equipment crafted by a city sex shop and trains her. ‘He took her thus through all the stages of a falcon’s training’, says Bayer, ‘telling her always that when she was sufficiently trained he would let her fly free and make her kill.’

20

Its final tableau is of a jessed, belled, near-mute and brainwashed woman who has just committed the ritual murder of her captor,standing ‘still like a statue, a monolith, an enormous bird, her arms outstretched, her posture hieratic, a cape sewn with a design of feathers falling from her arms like giant wings’.

21A happily less explicit story of transformation and desire is found in the Russian folk-tale

Finist the Falcon

. Marya works as housekeeper for her widowed father and two evil older sisters. They ask her father for fineries and silks; she asks for nothing but a feather from Finist the Falcon. Her father finally finds her one; delighted, she locks herself into her room, waves the feather– and a bright falcon hovers in the air before transforming itself into a handsome young man. Her jealous sisters hear his voice and break into her room, but Finist escapes as a falcon through the window. He returns to Marya the next two nights, but alas, on the third night Marya’s malicious sisters see him leave, and they fasten sharp knives and needles to the outside of her win- dow frame. The next night the unsuspecting Marya sleeps while Finist gravely injures himself trying to fly into her room. Finally he cries farewell to her with the words ‘if you love me, you will find me’ and flies away. In the way of such tales, Marya is finally reunited with Finist after a long quest – and of course they live happily ever after.

falcon transformations

A familiar tale of falcon transformation in Indian mythology is the

Sibi-Jâtaka,

in which the gods Indra and Agni test the charity and compassion of the king of the Sibis by changing themselves into a falcon chasing a dove. The terrified, exhausted dove flies into the king’s lap and the king offers it protection. But the falcon is outraged. ‘I have conquered the dove by my own exertions and I am devoured by hunger!’ it exclaims. ‘You have no right to intervene in the differences of the birds. If youprotect the dove, I shall die of hunger. If you must protect it, then give me an equal weight of your own flesh in return.’ The king of the Sibis agrees, commands that scales be brought and places the dove upon them. He cuts some flesh from his thigh with a knife. It is not enough to balance the dove, so he cuts more. Still not enough. The dove grows heavier and heavier as the king cuts flesh from his arms, legs and breast. Finally the king realizes that he must give all of himself, and sits upon the scale. With this, music is heard and a sweet shower of ambrosia falls from the skies to drench and heal the king. Indra and Agni reassume their divine forms, well pleased at his compassion, and announce that the king shall be reincarnated in the body of the next Buddha.

Another divine falcon transformation occurs in Germano- Norse mythology: Freja, goddess of fertility, possessed a falcon-cloak that transformed its wearer into a falcon. But humans, as well as gods, can shape-shift and become falcons. The hero of East Slavic

bylini

, epic warrior-class poems, is a

bogatyr

, a term related to the Turkic and Mongol term

bagadur,

or ‘hero’. The

bogatyr

Volkh Vseslavich could change into a bright falcon, a grey wolf, a white bull with golden horns and a tiny ant. Shamanic mythic sources lie deep; the

bogatyr

’s name is related to the Slav term

Volkhv

, signifying ‘priest’ or ‘sorcerer’. In the 1970s Marvel Comics’ first black superhero, The Falcon

,

teamed up with Captain America to fight evil, aided by The Falcon’s trained falcon ‘Redwing’. Such stories of human–animal transformations have fascinated critics for years: what do they mean? Do they subvert hegemonic versions of social identity? question what it means to be human? articulate religious or gender anxieties? Or are such transformations creating mon- sters in order to destroy them in fables wrought to reinforce the status quo?

When mere humans assume falcon form, lessons are gener- ally to be learned. The young mage Ged, hero of Ursula Le Guin’s

A Wizard of Earthsea,

transforms himself into a peregrine, a ‘pilgrim falcon’ with ‘barred, sharp, strong wings’ to attack the winged, malevolent demons who have just torn apart his female companion. He flees across the sea, ‘falcon-winged, falcon-mad, like an unfailing arrow, like an unforgotten thought’. UltimatelyThe

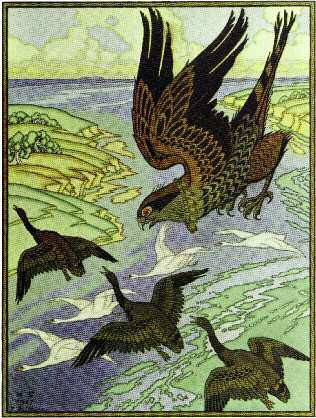

bogatyr

Volkh Vseslavich assumes the shape of a falcon in a 1927 water- colour by the Russian artist Ivan Bilibin.Le Guin’s novel is a meditation on the importance of recogniz- ing and accepting one’s true self. By manifesting his overwhelming emotions in falcon form Ged puts himself in jeopardy; for the price of shape-shifting is ‘the peril of losing one’s self, playing away the truth. The longer a man stays in a form not his own’, the text explains, ‘the greater the peril.’ Pilgrim-falcon Ged seeks out the mage Ogion, his old teacher, and alights on his hand. Ogion recognizes him, weaves a careful spell and transforms the falcon back into human form – a silent, gaunt figure, clothes crusted with sea-salt, with ‘no human speech in him now’.

Other books

Streak of Lightning by Clare O'Donohue

Mistress of the Hunt by Scott, Amanda

The Unexpected Duchess by Valerie Bowman

A Way in the World by Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul

Those Angstrom Men!. by White, Edwina J.

The Dream Spheres by Cunningham, Elaine

Guardian's Hope by Jacqueline Rhoades

Goblins Vs Dwarves by Philip Reeve

Unfamiliar by Cope, Erica, Kant, Komal

The Colony: A Novel by A. J. Colucci