Falcon (5 page)

Migrating falcons still perch on ships.

Clearly, ships are not optimal falcon habitats. But the genus

Falco

is not tied to particular landscapes; that characteristic falcon silhouette can be seen over city centres, deserts, arctic ice-cliffs and in the humid air above tropical forests. The large falcons tend to be solitary animals outside the breeding season, although pairs of some species such as lanners hunt coopera- tively all year. Lanner falcons in arid regions also congregate in groups at waterholes where prey is concentrated, or may assemble in loose flocks to feed on termite swarms.breeding

Falcons time their breeding to coincide with maximum prey abundance; young falcons are reared and fledge when there is plenty of inexperienced juvenile prey to catch. Most temperate- zone and high-latitude falcons return from their winter territories to their breeding territories early in the year, pair up and lay their eggs in spring. Their breeding territory is generally much larger than the winter territory of single birds, for far more prey is required to feed a family. Its size varies in relation to the availability of prey in the surrounding environment; the breeding territory of the prairie falcon, for example, may be as few as 30 or as many as 400 square kilometres.

This territory may contain several alternate nest sites used from year to year; bare ‘scrapes’ on ledges, in cliff potholes or on river cutbanks; or the reused nests of other large birds, such as ravens and eagles. Falcons do not build their own nests. Some peregrine populations nest in trees; one now-extinct population relied on the hollow tops of dead old-growth forest trees in Tennessee. Traditional nest sites can be ancient: gyr eyries in Greenland may go back thousands of years. The Karok Indians of north-west California considered the peregrine, which they

called

Aikneich

or

Aikiren

, to be immortal, for a pair had nested at the summit of

A’u’ich

(Sugarloaf Mountain) since time imme- morial. Some British peregrine eyries have been recorded as occupied since the twelfth century, and some, like those of Lundy Island, produced young celebrated for their prowess as falconry birds. There may be some truth underlying such tales of ‘special’ eyries. Young falcons tend to return to the area where they were reared. This high degree of philopatry may contribute to speciation in the genus, with local genetic traits reinforced over many years.High nesting densities of otherwise territorial raptors can occur when prey is abundant but nesting sites unevenly con- centrated. On the gorges of the Snake River in Idaho, for example, some kilometres from the gorge made famous by Evel Knievel’s failed attempt to jump it on a jet cycle, approximately one pair of prairie falcons nests per 0.65 km. These pairs hunt the numerous ground squirrels in the sagebrush desert that extends out from the river gorge. In steppe and prairie grasslands a lack of nest sites may limit falcon populations, even though prey populations may be high enough to support numerous pairs.

A peregrine falcon drives a raven from its nesting territory in this engraving by the renowned bird and sporting artist George Lodge (1860–1954).

Falcons don’t build nests; some species lay their eggs on ledges, while others often use old buzzard or raven nests, like this saker in Mongolia.

Conservation management techniques involving the erection of artificial nesting platforms have proved successful in some cases, but some falcons require no such habitat augmentation. Saker falcon ground nests have been found in Mongolia, and there are large populations of ground nesting peregrines in the Arctic. Ground nesting is a dangerous game, exposing eggs and young to predators, and mutualistic relationships with other species have developed. On the Taymyr Peninsula in Siberia otherwise vulner- able ground-nesting peregrine eyries are found in statistically significant proximity to Red-breasted goose

Branta ruficollis

colonies. If the vigilant geese spot arctic foxes, or avian predators, their alarm call alerts the falcons, whose aggressive dives to drive away the threat benefit both peregrines and geese.Large falcons generally breed in their second year or later, but there are numbers of non-breeding adults in the population at any one time. Gyrfalcons may not breed at all in years when lemmings or ptarmigan are scarce. Falcons are generally mono- gamous; extra-pair copulations are infrequent. Falcon courtship is not marked by colourful plumage; instead, males may perform dizzying courtship flights near possible nest sites, sometimes

joined by the female. Pair bonding is cemented by males bringing prey to the female and by elegant nest-ledge displays of bowing and calling. Frequent copulations – around two or three an hour before egg laying – further strengthen the pair bond. The single clutch consists of three to five blotched, rusty brown eggs, which are incubated by the female for around a month. The young, or ‘eyasses’, hatch with a thin covering of grey or whitish down that is replaced by a thicker coat a week or so later. Feather growth is rapid, quills breaking through the down as young falcons exercise their wings and their hunting instincts. They are playful in the nest, grabbing sticks, stones and feathers in their feet, turning their heads upside down to watch buzzing flies and distant birds, pulling on the wings and tails of their irritated siblings. They take their first unsteady flights aged around 40 to 50 days, after which the parents teach them the rudiments of aerial hunting strategies by dropping dead or disabled prey from a height for the pursuing young to catch.

Young falcons begin killing their own prey and disperse from the territory after four to six weeks, after which their mor- tality is relatively high. Around 60 per cent of young falcons die in their first year, mainly from starvation. This fact is surprising to many commentators who see falcons as the most efficient predators alive. Surprises like this occur when biology doesn’t match mythology – that is, when real animals don’t match the ways humans perceive them. Bedouin falconers, for example, who only saw migrating falcons in the desert, never breeding pairs, quite reasonably mapped their own gender concepts onto the falcons they trapped: they assumed that the larger, more powerful birds were male and the smaller, female. But scientific understandings of falcons, too, can be strongly inflected or invisibly shaped by our own social preoccupations. And con- servation is riven by conflicts arising because animals possess

Fledgling, or

eyass

, peregrines, in a well-observed 1895 gouache by the Finnish artist Eero Nicolai Jarnefelt. The left- most bird is ‘mantling’ protec- tively over food; the other is calling with the typical hunched posture of a food-begging youngster.different values for different cultures. Are falcons paradigms of wildness and freedom? vermin? sacred objects? a commercially valuable wildlife resource? or untouchable and charismatic icons of threatened nature? Investigating these different mean- ings has real-world implications. People conserve animals because they value them, and these valuations are tied to their own social and cultural worlds. The pictures and stories through which falcons are used to articulate and reinforce different cultural understandings of the world are

myths

, and they are the subject of the next chapter.- Mythical Falcons

Detective Tom Polhaus (picks up falcon statue):

Heavy. What is it?Sam Spade:

The, uh, stuff that dreams are made of.Polhaus:

Huh?(closing lines of

The Maltese Falcon

, 1941)On a foggy November dawn in 1941, the feisty American bird- preservationist Rosalie Edge was woken by the frantic alarm-calls of city birds. She peered from her Manhattan window into Central Park. What had caused this commotion? Blinking back sleep, she realized that the stone falcon she could see carved from a rocky outcrop was no statue. It was alive. Suddenly, time stood still. She was transfixed. My soul, she wrote, ‘drank in the sight’ of this impossibly exotic visitor to the modern world. Was it, she breathed, the ghost of Hathor, wandered from the Metropolitan Museum and overtaken by sunrise? But no: ‘time resumed as the swift-winged falcon swept into the air . . . the enchantment was broken’.

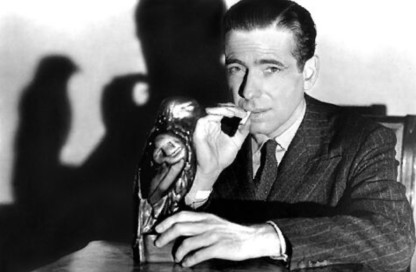

1Another ancient falcon worked its enchantments on Humphrey Bogart, Peter Lorre, Sydney Greenstreet and audi- ences across America that year. The small black statuette of

The Maltese Falcon

casts its dark shadow across the screen at the very beginning of John Huston’s

film noir

, and the audience reads the barest bones of its history in scrolling text:In 1539, the Knights Templar of Malta paid tribute to Charles v of Spain by sending him a Golden Falcon encrusted from beak to claw with rarest jewels . . . but pirates seized the galley carrying this priceless token

and the fate of the Maltese Falcon remains a mystery to this day.

Bogey and the black bird: Humphrey Bogart, the Maltese Falcon and their con- joined shadow in a publicity shot

for John Houston’s

1941 film.

While driving the plot, the Maltese Falcon remains a mys- tery. Although it reveals the characters of the people in the film

– all of whom desire or fear it – and the worlds in which they live, it is a mute object that reveals nothing more about itself. Likewise, that Central Park encounter at dawn tells us almost nothing about peregrines. But it tells us much about the writer herself and about the era she lived in, revealing some intriguing contemporary attitudes towards nature and history. In wartime America, it seems, falcons could be viewed as mystical manifest- ations of an age of theriomorphic gods and ancient ritual. But falcons carried many other meanings, too. Falcon-enthusiasts such as Edge saw them as living fragments of primeval wilderness

imperilled by the relentless encroachment of modernity. Writing about falcons in this period is commonly shot through with a gloomy romanticism akin to that displayed in the works of many contemporary anthropologists who saw the cultures they studied as exotic, primitive, vital and ultimately doomed by historical progress.

And falcons could be icons of history, as well as wild nature. Way back in 1893 a popular magazine described the ancient sport of falconry as having an ‘astonishing hold on the popular imagination of Americans’ with the image of a hooded falcon ‘as firmly impressed on the popular mind as that of St George and

The falcon as a token of a

medieval Golden Age: a detail from a 14th-century fresco by Simone Martini at the church of San Francesco, Assisi.

the Dragon’.

2

And the Second World War heightened this ability of falcons to conjure a lost golden age of medieval splendour. As America increasingly saw itself as the guardian of a European high-cultural heritage threatened by the dark forces of fascism, trained falcons made frequent appearances in Hollywood epics about the Second World War set in the Technicolor Middle Ages. And wartime falcons could also be seen as the biological counterparts of warplanes: heavily armed natural exemplars of aerodynamic perfection. This notion of falcons fascinated the military. It even led to real falcons being incorporated in defence systems – with varying success, as chapter Four shows. And, making all-too apparent the fact that falcon myths can carry real-world consequences, many Americans, viewing nature with crystalline conviction through their cultural lenses, inserted falcons into their own systems of morality: they viewed them as rapacious murderers of song- birds, enemies to be shot on sight.All these stories are the falcon-myths of 1940s east coast America. Calling them myths only seems odd because most are still being told. Today, falcons remain precious icons of wild nature; they remain elegant icons of medievalism; some still damn them for their ‘cruelty’ to other birds, and American f-16 Fighting Falcon jets are familiar silhouettes in many skies. As the saying goes, myths are never recognized for what they are except when they belong to others.

the falcon and the cock

Myths, then, are stories promoting the interests and values of the storytellers, making natural, true and self-evident things that are merely accidents of history and culture. They anchor human concepts in the bedrock of nature, assuring their audiences that

their own concepts are as natural as rocks and stones. The process is termed

naturalization

, nature being taken as the ulti- mate proof of how things are. Or how things

should be

: myths have a normative element, too. Sometimes this is obvious: the Kyrgyz proverb ‘feed a crow whatever you like, it will never become a falcon’, for example, makes inequalities between people natural facts, not merely accidents of society. Fables work similarly to naturalize the storyteller’s social mores. But the nor- mative strength of fables is sneakily increased by the way readers are complicit in the myth-making, taking pleasure in working out the moral before reading it themselves. Thomas Blage’s 1519 animal fable

Of the Falcon and the Cock

begins with a knight’s falcon refusing to return to his fist.A Cock seeing this, exalted him selfe, sayeing: What doe I poore wretch alwayes living in durte and myre, am I not as fayre and as great as the Falcon? Sure I will light on hys glove and be fedde with my Lords meate. When he had lighted on hys fiste, the knight (though he were sory) yet somwhat rejoyced & tooke the Cock, whom he killed, but hys fleshe he shewed to the Falcon, to bring him againe to his hand, which the Falcon seeing, came hastily too it.

3Blage’s moral hammers home the message: ‘Let every man walke in his vocation, and let no man exalte him selfe above his degree.’ His fable rests on a robust and ancient perception of falcons as noble animals. Refinement, strength, independence, superiority, the power of life and death over others – for millen- nia these have been assumed features of falcon and nobleman alike. Consequently, falcon myths often reinforce human social hierarchies through appealing to the straightforward ‘fact’ that falcons are nobler than other birds.

In early modern Europe the worlds of humans and birds were thought organized in the same way, shaped according to the same clear social hierarchy. Royalty sat at the top of one, raptors at the top of the other, and the class distinctions between various grades of nobility were paralleled by species distinctions between various types of hawks. Often misread by modern falconers as a prescriptive list of who-could-fly-which- hawk, the fifteenth-century

The Boke of St Albans

illustrates this correspondence with sly facility; a kind of

Burke’s Peerage

meets

British Birds

:Ther is a Gerfawken. A Tercell of gerfauken. And theys belong to a Kyng.

Ther is a Fawken gentill, and a Tercell gentill, and theys be for a prynce.

There is a Fawken of the rock. And that is for a duke. Ther is a Fawken peregrine. And that is for an Erle. Also ther is a Bastarde and that hawk is for a Baron. Ther is a Sacre and a Sacret. And Theis be for a Knyght. Ther is a Lanare and a Lanrett. And theys belong to a

Squyer.

Ther is a Merlyon. And that hawke is for a lady.

4While the existence of this natural hierarchy was unques- tionable, with sufficient social authority one could be iconoclastic within its bounds. Thus the Chancellor of Castile, Pero López de Ayala, could declare his preference for the nobly conformed peregrine over the gyrfalcon, for the latter was ‘a villein in having coarse hands [wings] and short fingers [primaries]’.

5Such notions of parity between hawk and human exemplify that ferociously strong aspect of

Kulturbrille

in which humans

assume that the natural world is structured exactly like their own society. A Californian Chumash myth held that before humans, animals inhabited the world. Their society was organized in ways just like that of the Chumash themselves, with Golden Eagle chief of all the animals, and Falcon,

kwich,

his nephew. Such parallels seem obvious. But they may be hidden deep. Sometimes their very existence is surprising – particularly when they occur in ‘objective’ science. But they are there. Furthermore, ecologists have routinely inflected their under- standings of predation ecology with concerns relating to the exercise of power in their own society. Sometimes mappings‘Ther is a Gerfawken . . . and theys belong to a Kyng’. On his throne, King Stephen feeds a white gyrfalcon.

From the

Chronicle of England

by Peter de Langtoft,

c

. 1307–27.from human to natural world have assumed moral, as well as functional, equivalences between raptors and humans, particu- larly in the ways each are respectively supposed to maintain stability in nature and society. This kind of analogical thinking can reach alarming heights. In 1959 soldier, spy and naturalist Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen wrote that the role of birds of prey was to weed out the weak and unfit. Without birds of prey, he maintained, one finds ‘decadence reducing birds to flightless condition and often to eventual extinction’.

6

Peace leads to the decline of civilization, for Meinertzhagen. Fear is necessary to maintain social order. Without predators birds ‘would become as gross, as stupid, as garrulous, as overcrowded and as unhappy as the human race is today’. ‘Where absolute security reigns, as in the pigeons of Trafalgar Square’, he wrote, ‘then there is no apprehension. I should dearly love to unleash six female goshawk in Trafalgar Square and witness the reaction of that mob of tuber- culous pigeon.’

7

You don’t need to have read Nietzsche to comprehend the subtext here, or when Meinertzhagen describes the mobbing of predators by ‘hysterical, abnormal, irresponsible’ flocks of birds as ‘atrocious bad manners’.

8

Other books

The Beast of the Camargue by Xavier-Marie Bonnot

Erun (Scifi Alien Romance) (The Ujal Book 4) by Celia Kyle, Erin Tate

Devil Takes A Bride by Gaelen Foley

Tea for Two and a Piece of Cake by Shenoy, Preeti

The Portrait by Iain Pears

A Surrendered Heart by Tracie Peterson

A World Away (A New Adult Romance Novel) by Lacroix, Lila

The Heart Breaker by Nicole Jordan

Heteroflexibility by Mary Beth Daniels

The Rose Garden by Marita Conlon-McKenna