Eyes on the Street: The Life of Jane Jacobs (63 page)

Read Eyes on the Street: The Life of Jane Jacobs Online

Authors: Robert Kanigel

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Women, #History, #United States, #20th Century, #Political Science, #Public Policy, #City Planning & Urban Development

“Thank you very much for the

first terrific pages of

Uncovering the Economy: A New Hypothesis

,” Ebershoff wrote Jane in response to her twenty-eight-page piece of it.

If the rest of the book reads as Part 1 does—and why shouldn’t it!—you’d have done just what I was hoping for; and what your many readers will want. I’m very pleased that this isn’t merely an anthology of your greatest hits. You’ve hit on a new but profound idea about cities and economies…Please keep writing. Please keep sending me pages. I hope you’re healing swiftly and that you have many long hours to write and think.

Jane’s decline in her later years, before 2005 or so, did not extend to her mind. If it did, we might expect to find it in her correspondence, closer to her raw, unmediated self. But it’s not there. Not in her spelling. Not in the organization of her thoughts. Nor in their characteristic energy and spirit. In 2005, she apologized to a correspondent for not replying earlier: “

You must think that I was swept silently into the Grand Canyon.” She’d had another accident, fallen and broken her leg “badly enough that I’ve had to try to relearn how to walk…This is a boring tale of woe—but what is upsetting, rather than boring, is that no, I haven’t done the blurb you were expecting for your U. of Michigan Press book on development.”

“Don’t send me a Get Well card,” she added. “I am getting well; it’s just slow.”

Back in 2002 Jane had suffered a serious stroke. It happened in the middle of the night. She called Jim, who got her to the hospital, where she stayed for a couple of weeks before entering a rehab unit. Half her body was paralyzed. She had trouble swallowing. She couldn’t type, couldn’t write. But she could think just fine. It was there, as Jim tells it, that she conceived

Dark Age Ahead.

She was in a hurry, “determined to get as much done as she could, before the deadline.” After leaving the hospital, “from outward appearance unscathed,” she wrote with uncharacteristic nervous energy, rushing it through. “It was the only book she wrote out of her head, without notes.”

Ned, in from the coast, helped Jane with the index and entered her text into the digital form her publisher required. The two of them sat “at the screen together,” as he remembers, going over a word choice here, an idea there. “It was a wonderful learning experience for me,” he says. As Jane acknowledged, he contributed to the “

Unwinding Vicious Spirals” chapter, pushing her for ideas about “how to get out of this mess,” the sad, cultural decline that was her subject. Otherwise, the book was her own. But it came slowly, at great cost. Jane relied on family and friends in ways she hadn’t before. Her signature, normally rounded and clear, was now jagged, angular, and scratchy. Every little thing came harder.

Until near the very end, at least, her mind remained clear. More than clear—

engaged

, eager for any bit of life she could still grab hold of. But finally, sometime late in 2004, maybe around Christmas, David Ebershoff began to realize that the hope he’d voiced for Jane “healing swiftly” was unrealistic; the seesaw battle between recovery and decline was settling in one direction only. After the Mumford Lecture in May, he recalls, she seemed to be struggling. As the months went by and he checked in with her, “she’d say she was trying to write, but I could see how hard it was for her.” In some of their later phone calls, “I couldn’t have the same kind of conversation with her.” Ebershoff’s counterpart in Toronto, Anne Collins, noticed much the same: what had seemed almost regular cycles of weakening and renewal now ebbed permanently into decline. Sometimes Anne would drop by the house for tea. But now there were no “So, how’s the writing?” questions for Jane. It was just tea.

Jim Jacobs, of course, had seen it coming earlier, following his mother’s return from the

Dark Age Ahead

tour: “Pat and I noticed that something was seriously wrong.” This woman who spoke in perfect paragraphs now could hardly speak at all. Sentences drifted. Jane realized it, too. “She

knew there was trouble.” Her doctors found evidence of mental slippage now but, to Jim’s taste, were too inclined to say,

Well, it’s about what you’d expect for a woman her age, we have to let nature take its course.

Looking for a way out, he thought he saw improvement when she happened to be on an antibiotic regimen and suspected infection was worsening her mental condition.

In late summer of 2005, Jim took a leave of absence from the company he’d cofounded to care for Jane himself. “But it was more than I could do,” so they brought in round-the-clock nursing care. Late that year and early the next was the worst of it. Jane would slide into unpredictable outbreaks of anger, affection, and despair. “What was I thinking?” she’d say as she came out of one of them. It was hard for her, hard for everyone.

It was not a happy time for those who loved Jane Jacobs. She had broken her hip the year before, was confined to the house, increasingly isolated. There were times, relates Jim, when “she was in no condition to see people,” which upset some of her friends, who felt that maybe she was being kept more isolated than need be. It seemed to Roberta Gratz that Jane “hungered for company.” When friends did visit, they honored Jane’s voracious sweet tooth. Margie Zeidler would come by with butter tarts. John Sewell and his wife, Liz Rykert, started bringing her Saturday meals. They’d show up, march into the kitchen, get things organized, lay out a meal, break out the Basque tarts that were one of Jane’s favorites, and sit down and talk. “She had lots of opinions about the world,” says Sewell. But rarely did she reminisce; this was one old-timer who took no refuge in the past, at least in public; who knows what she whispered to Ben Franklin or one of her other old friends?

Jim, his daughter Caitlin recalls, was desperate for “a solution that would make her well,” delving into medical science, looking “for what he could do to save her.” Early in 2006, with Jane on a regimen of antibiotics Jim had prevailed on her doctors to prescribe for her, Jane seemed to rally, her mental acuity, speech, and emotional stability improving. For a time she found her way back to work again, mainly on the economics book. She’d never much talked about work in progress, but now she seemed eager to tell Jim about it. Up until March, maybe April, she was still at the typewriter.

Finally came the sudden turn for the worse; Jim took her to the hospital, stayed with her almost nonstop until, three days later, on April 25, 2006, she died. The family issued a statement: “What’s important is not

that she died but that she lived, and that her life’s work has greatly influenced the way we think. Please remember her by reading her books and implementing her ideas.”

And if you don’t, Ned Jacobs was

supposed to have joked, “there’s a Dark Age Ahead.”

Jane was cremated, her ashes laid to rest in Creveling Cemetery, down the Old Berwick Road from where her mother had grown up in Espy, in the Butzner family plot, beside Bob, their common stone recording their names, dates, and nothing else.

—

“When someone like that dies, she doesn’t go anywhere,” says Jason Epstein. “She’s not dead. She’s so vivid, you can’t imagine her dead, like Shakespeare.” Maybe so, but we are enjoined to consider her legacy, what the example of her life holds for us. The word itself carries some stuffy baggage, but I don’t think Jane would have dismissed the question or, with false modesty, scolded us for raising it.

Jane’s legacy was, first of all, more than

The Death and Life of Great American Cities

, more than any of her individual books. This might seem heretical to assert for a woman who was author first of all and who said so time and again. “I am quite an ordinary person, I assure you,” she wrote in 1997, “who has led a happy ordinary life, the only perhaps notable things about it having occurred in my head as I sit undramatically at a typewriter; and those things are already in my books.” Still, Jane was wife, mother, and friend, too. She was social activist, gadfly, rogue, and rebel. She was an economist of sorts, and something of a philosopher, and, one hears it said, an expert on cities, too.

These clumsy qualifiers nod to Jane’s uncredentialed relationships to the very fields and disciplines to which she contributed most. Similar reservations might apply to Jane-as-scientist, which she was, too, in a way. “She was a great theoretician,” says Lucia Jacobs, tenured professor of psychology at UC Berkeley. “She identified with Darwin.” When people complained about the absence of hard data in her work, Jane would reply, “Darwin didn’t have data either.” Professor Jacobs deems Darwin quite the creditable comparison for her. “Darwin went his own way, knew he was right, and had unbelievable intuition.” Like Jane.

Professor Jacobs means “theoretician” as praise, certainly when uttered in the same breath as Charles Darwin; so did Robert Lucas, the Nobel-winning economist, in applying the word “th

eorist” to her. And

yet, the more Jane was theoretician, the less she was the kind of writer she’d arrived in New York to become. In those early articles she wrote for

Vogue

, Jane was rooted in fact, datum, and incident, in sidewalk and street, leather, flowers, and furs. But in the years after

Death and Life

, lauded as an important thinker, she might be excused for slipping back from the rough-and-tumble of the world and into the cosseted realm of ideas: Economics. Morals. Ecology. As age and physical frailty kept her more at home,

retreat to the abstract and theoretical probably became easier, even inevitable. She became less the maker of vivid images and scenes, more the intrepid explorer of ideas. Of course, the two were always in her, locked in creative tension;

Death and Life

is stocked to the brim with ideas. But as the years passed and the public intellectual in her bloomed, Jane did find it harder, or maybe less important, to rid her prose of generalization and abstraction—leaving more of it behind to sometimes thwart or entangle her readers.

—

In the years leading up to her death, and then after it, critics began to notice that within the space of a few years in the early 1960s,

three women wrote three classic books, launching three social movements that changed the world: Betty Friedan’s

The Feminine Mystique

, Rachel Carson’s

Silent Spring

, and Jane’s

The Death and Life of Great American Cities.

All three women identified primarily as writers, not as credentialed experts in the fields about which they wrote; Carson, with a master’s degree in zoology, was a partial exception, but by age thirty, long before she wrote

Silent Spring

, she was making a living as a writer, her childhood dream. All three were popularizers; that is, just as they were not themselves traditional scholars or scientists, they did not write

for

scholars but for ordinary, nonexpert readers. Mostly, they avoided specialized vocabulary, used language intended to draw in, not exclude. And, rather than hide their deepest convictions beneath a patina of objectivity, they expressed themselves with intensity and feeling.

Friedan, Carson, and Jacobs had something else in common, of course, which is that they were women. However much or little their books might be judged expressions of “women’s thinking,” or “women’s sensibilities,” they surely reflected women’s

experience.

In the 1940s and 1950s, when the three of them came up, that normally meant working lives not so tied to professional discipline or traditional career arc as men’s were; more often bound to steno pad and typewriter, or to the bearing and care of

children; and routinely undercut by the sort of crude sexist barbs Lewis Mumford aimed at Jane in “Mother Jacobs’ Home Remedies.” (“Mr. Mumford,” Jane got back at him in her Mumford Lecture at City College, “seemed to think of women as a

ladies’ auxiliary of the human race.”)

Even as recently as 2011, critics who should have known better were still calling Jane a housewife. Veronica Horwell, writing in

The Guardian

, pictured her as

pushing a baby carriage after she married Bob. Sir Peter Hall termed her “a middle-class housewife who found her voice.” Well, Jane was

never

a housewife, not if by that we mean someone who sees her primary role as at home, who is “just” a housewife. Jane was a good wife, and tended the house as best she could, which wasn’t all that great, turning to paid outside help when she could. Aside from brief maternity leaves, she

always

worked, viewed the great world of ideas and action, of politics, buildings, and books as her natural and settled domain.

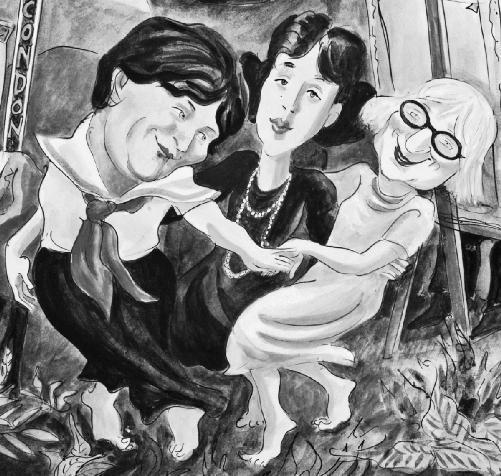

Jane sometimes wound up in the most unlikely places. Here she dances with Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney and Willa Cather, in a mural by Edward Sorel installed at the Waverly Inn, a restaurant in Greenwich Village.

Credit 32

Back in 1971 Jane read

Man’s World, Women’s Place

, an influential early feminist book by Elizabeth Janeway that took on myths of women’s weakness and women’s power, and had plenty to say about both. In a

letter to Jason Epstein around the time her family was moving into the Albany Avenue house, she called it “

the first book on the subject of women’s fix that has not just depressed and enraged me, but has enlightened me.” She appreciated Janeway’s ideas about why sex occupied the place it did in advertising and art. “Also a very nice treatment of that bugaboo about women fucking men into limbo if given the chance, and the best (because it is so true) put-down of penis envy.”