Eyes on the Street: The Life of Jane Jacobs (61 page)

Read Eyes on the Street: The Life of Jane Jacobs Online

Authors: Robert Kanigel

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Women, #History, #United States, #20th Century, #Political Science, #Public Policy, #City Planning & Urban Development

A few years later, in June 2001, Michael Illuzzi, executive director of a Scranton museum, wrote Jane that he was working on a book, “

Cityscapes, Sidewalks and Scranton: Jane Jacobs and the New Urbanism,” for which he wished to interview her. No, Jane wrote back, if he wanted to know how the New Urbanists viewed her, talk to them, not her. As for Scranton, he didn’t need her for that, either, “except possibly as a gimmick and that I will not be.” When, a few weeks later, Illuzzi wrote again, pressing his suit, Jane shot back, “I have no interest in a book about my work and no time or inclination to become interested. If you persist in undertaking it, it will be without any cooperation from me.”

But while Jane could be dismissive, a thoughtful letter from out of the blue could sometimes excite her interest, luring her into lengthy correspondence. Early in 2000, she received a long letter from a PhD student, Timothy Patitsas. “

These past six months,” it began,

I have been considering the question you pose at the end of

The Death and Life of Great American Cities

, about the kind of problem a city is, in connection with a doctoral thesis I am undertaking for the department of Theology at the Catholic University of America. I am trying to place the New Urbanism in a broader philosophical and theological context through a study of the modern antipathy toward liturgy.

From this not entirely promising start, Patitsas launched his argument. For the Le Corbusiers and Ebenezer Howards of the world, he wrote,

“the City is dead matter to be manipulated by the reasoned plans of a single will, for the benefit of a unitary gaze, while nature is a dumb garden to be manipulated cutely.” Jane’s approach, on the other hand, could be seen as “liturgical.” In this provocatively unfamiliar sense, the city could be appreciated for its “openness to the unknown, built around recurrent cycles of death, rebirth and risk,” the product of “many actors freely relating and contributing their own dreams and vision.”

If maybe a bit of a stretch, still it must have flattered Jane to see her work of four decades earlier the object of such fresh thinking. Thoughtful engagement was what she lived for. Patitsas’s ideas were so surprising and original—which was what it took to get Jane in gear with you intellectually. “Thanks so much for your astonishing and enlightening letter,” she replied. She’d never thought much about liturgy, she said, owning up to her own almost nonexistent religious feeling. And with at least one of Patitsas’s key arguments, she agreed entirely: conventional city planning didn’t worry much about the passage of

time

, and that went as well for the New Urbanism. Its communities didn’t develop organically but were built whole, from scratch: you planned your charming little town, you realized your plans, whatever they were, and that was that—done, finished. But this indifference to the workings of time, Jane wrote Patitsas now, “means almost everything important is left out: trial and error, risk and dreams, birth, death, success, failure, celebration, regret, relationship…the whole chain of being. You’ve put it beautifully.” Not surprisingly, this was not the end of their intellectual relationship, which stretched across Jane’s remaining years.

The attention to Jane during this period came to her as a Canadian. While her first two books were conceived and written in the United States, she wrote more books, over a longer time, in Canada than she did in the U.S. She’d come to love Canada and seems never to have seriously considered leaving it. Her three U.S.-born children and their families, spread out across the breadth of the country—Jim in Toronto, Burgin in rural British Columbia, Ned in Vancouver—all lived as Canadians.

In the cases of the Spadina Expressway and the St. Lawrence project, as we’ve seen, Jane exerted a marked influence on Toronto. Later, the resurgent health of two former industrial districts along east and west King Street in downtown Toronto, together known as “

the Kings,” also owed much to her. Out of meetings between Jane and local planners and architects in the mid-1990s emerged a plan to free these two loft

districts from most zoning restrictions; within their four hundred acres, you could do pretty much as you pleased, so long as you didn’t raze sound old buildings. It would “allow the city to organically define itself,” says Ken Greenberg, a friend of Jane’s and one of the scheme’s champions. The experiment spewed forth new businesses, bustling entrepreneurial laboratories, new residences. In 1996, virtually no one lived in the Kings; today, thousands do. Over the years, it’s been estimated, the Kings downzoning injected $7 billion into the city, 38,000 jobs. “

It’s magical, it’s wondrous,” Jane told an interviewer in 2001, “how fast those areas have been blossoming and coming to life again.” Barry Wellman, a University of Toronto sociologist and another transplanted American, noted that whereas Jane “

saved one neighbourhood in Manhattan she saved many more in Toronto by word, deed, and inspiration.”

Take the elevator up to the observation deck of Toronto’s signature CN Tower, look out over the city from a thousand feet up, and you see Corbusian towers, hundreds of them, condos and offices, parading north along Yonge Street as far as the eye can see. Below, the elevated Gardiner Expressway, slipping around and through the downtown lakefront, pulsing with traffic, reminds you of nothing so much as the Futurama exhibition at the New York World’s Fair. In short, Jane Jacobs didn’t singlehandedly transform Toronto into a twenty-first-century Greenwich Village. Still, in its vitality, Toronto stands as an affront to struggling American cities like Buffalo and Detroit on the other side of the border. It is dense with new immigrants, its streets bustle with life, it boasts enormous cultural vitality. “The mere fact Jane Jacobs chose to live in Toronto,” wrote the local journalist Kelvin Brown at the time of her death, “came to be an endorsement for the city’s brand. She was synonymous with the notion of a livable city and her Toronto residency was proof that we, in Toronto, inhabited a special place.”

During the thirty-three years she’d lived in Toronto, Jane said in 2001, “

so many parking lots and gas stations in valuable locations have been replaced by dwellings, working places, and cultural institutions that it’s hard to buy gasoline or park on the surface in the center of the city.” She meant this to celebrate the flowering of a more vital, less car-oriented—yes, more Jacobsean—city. But some Torontonians never wanted that at all. “

The first hit our city took was the arrival of Jane Jacobs,” declared one eighty-year-old blogger and self-described former “repairman, mister-fix-it and mechanic” made livid by the daily gridlock of

Toronto traffic. For this he blamed Jane, who, once in Toronto, “started selling her snake oil. Which amounted to her proclamation that cities are for people not cars. It is a grossly stupid idea and appeals to dreamers.” The master plan for new highways in Toronto, he pointed out, went back to 1948; stopping the Spadina unraveled it, “twenty years of work went down the drain,” and it was Jane’s fault and that of the cabal around her.

John Downing, a longtime local journalist, also faults Jane, whom he labels a classic “

shit disturber.” Years ago, Downing took an urban geography course at the University of Toronto; “they might as well have had a statue of Jane in the front of the room,” so closely did it track her ideas. Those ideas, he says, did the city grievous harm. The Spadina would have benefited more people than it would have hurt. So would the enlargement of the little airport on Toronto Island, which Jane successfully opposed in part for its air and noise pollution. John Downing knows his Jane Jacobs: “I don’t believe in ‘eyes on the street,’ ” he says, “but I’ll never forget that imagery” from her book. And he’s glad for people like her “who express strident views.” Even so, he reckons Toronto worse for her influence: Traffic inhibited. Truck suspensions bashed up and gas wasted by traffic-impeding speed bumps installed at the behest of Jane’s anti-car cronies. Jane a guru? No, he wrote in a 2006 column, she was more “a sentry outside the urban camp, challenging everyone from generals to privates, insisting only she knew the password. The tragedy in her adopted city is that many of us liked it the way it was before she came.”

True, Jane’s friend Max Allen sums it up, some in Toronto did see her as “an old fogy, standing in the way of progress. And they said it was hard to argue with her.” (Because, he adds, “she was right.”) And yes, he allows, a kind of cult did form around her, where to criticize her made you practically an apostate. But, blame or praise, it was “immaterial to her. She was absolutely sure of herself and absolutely not full of herself.”

Mostly, Jane’s affection for Canada was abundantly reciprocated. Her friend Toshiko Adilman tells of Jane on the eve of a trip to Japan, realizing at the last minute that she had no visa, at which point the whole Canadian government, so it seemed, was enlisted to get her one. In 1991, Toronto held a Jane Jacobs Day of public appreciation, with an afternoon symposium and a formal dinner that evening. “Through it all,” the Toronto author Robert Fulford would recall, Jane “

smiled benignly, a tall, stooped woman with the look of an ancient hawk.” In 1996 Jane was awarded

the Order of Canada. “You are now entitled to use the initials O.C. after your

name, and to wear the lapel pin,” an official of the order’s council advised Jane that July, enclosing two pins together with guidance on “the Order of Precedence for the Wearing of Orders, Decorations and Medals.”

All this was just a preview for the conference, celebration, lovefest, or whatever it was, held in Jane’s honor across five days in October 1997—lectures, debates, and tours going on into the night on subjects dear to Jane’s heart. Conceived by Alan Broadbent, John Sewell, and others among her friends, the earliest discussions bloomed into an advisory committee, the hiring of staff, and the selection of speakers. “

Ideas That Matter” is what they called it, and it was probably the only thing they

could

have called it: for Jane, ideas were most of what mattered to her. And it was her ideas that mattered most about her to Canada and the world.

At first, Jane had mixed feelings. But once the program, listing its substance-stuffed phantasmagoria of events, came out, she sent it to her brother John, taking care to assure him and his wife that they needn’t feel obliged to come. “

I agreed they could do this, with three stipulations,” she explained, maybe a little defensively—“that I wouldn’t have to be involved in organizing it, wouldn’t have to make a speech, and that they wouldn’t invite any windbags.”

Eighteen months and half a million dollars in the planning, Ideas That Matter was all a-bubble with intellectual ferment: Livable cities, human ecology, and self-organizing systems. The future of Toronto’s Yonge Street. The Magic of Local Currencies. Biomimicry. “

So bedazzling were the array of ideas presented here,” wrote one attendee,

The

Globe and Mail

’s Don Cayo, “so rapid-fire did they fly, my head still spins.” Inevitably,

Death and Life

was well represented, as in a session on “Why We Love Density, Congestion and Crowding.” Each afternoon at 5 p.m., Jane held forth in a one-hour public conversation with one or another prominent interviewer. With one of them, Peter Gzowski, she told of her visit to Hong Kong, marveled at how its residents started up tiny hotels by combining apartments, how with a washing machine or two they’d start up a laundry. “They have all kinds of improvisations on how to make a living…all kinds of little manufacturing things going on that are ostensibly just residences.” Onstage, sitting back in an armchair, she enjoyed herself, a laugh sometimes sweeping through her whole body, gleeful eyes scrinching into slits, cheeks alive with color.

Soon after Ideas That Matter, Jane was treated to a hot air balloon ascension. “

Have you ever been?” she wrote Ellen Perry afterward. “Do,

if you get a chance. Absolutely the only sounds coming from earth were the barking of dogs, and they were as clear as could be.” This was her news—along with word that her latest book,

The Nature of Economies

, was coming out soon.

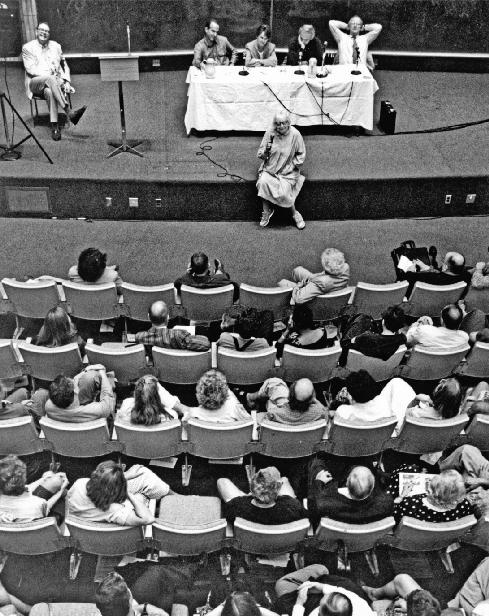

Jane at the Ideas That Matter conference in Toronto in 1997

Credit 31

III. OBEDIENCE TO NATURE

The last chapter of

Death and Life

, “The Kind of Problem a City Is,” had looked at cities in a way bordering on the biological. “

At some point along the trail,” Jane wrote in a new 1992 foreword to it, “I realized I was

engaged in studying the ecology of cities. Offhand, this sounds like taking note that raccoons nourish themselves from backyard gardens and garbage bags,” as apparently they did in Toronto. That’s not quite what she was getting at. The ties between natural and urban ecosystems, however, were myriad. Both featured intricate webs of connection. In both, diversity developed organically. Both are “easily disrupted or destroyed.” This, in brief, was Jane’s thinking about urban ecology around 1992. Now, with

The Nature of Economies

, she was developing these ideas, particularly in relation to healthy economies. Economies grew, or didn’t, said Jane, largely in obedience to laws of nature like those governing biological systems.