Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things (21 page)

Read Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things Online

Authors: Charles Panati

Tags: #Reference, #General, #Curiosities & Wonders

Hand-gluing paper bags and boxes. A machine to mass-produce flat-bottom grocery bags was patented in 1883

.

Charles Stilwell died on November 25, 1919, in Wayne, Pennsylvania, but not before his fertile mind had invented a machine for printing on oilcloth, a movable map for charting stars, and at least a dozen other brainstorms. The masterpiece of his career, though, is patent number 279,505, the machine that made the bag at once indispensable and disposable.

Friction Match: 1826, England

Homo erectus

, a forerunner of modern man, accidentally discovered fire through the friction generated by two sticks rubbed together. But 1.5 million years would pass before a British chemist, John Walker, produced instantaneous fire through the friction of a match rubbed over a coarse surface. Ironically, we know more today about

Homo erectus

than we do about John Walker, who also made his discovery by accident.

Other inventors and scientists had attempted to make matches. The first friction device of note was the Boyle match.

In 1669, an alchemist from Hamburg, Hennig Brandt, believed he was on the verge of transforming an olio of base metals into gold, when instead he produced the element phosphorus. Disappointed, he ignored the discovery, which came to the attention of British physicist Robert Boyle. In 1680, Boyle devised a small square of coarse paper coated with phosphorus, along with a splinter of wood tipped with sulfur. When the splinter was

drawn through a folded paper, it burst into flames. This marked the first demonstration of the principle of a chemical match. However, phosphorus was scarce in those days, so matches were relegated to the status of a costly, limited-quantity novelty. They disappeared before most Europeans—who kindled fires with sparks from flint striking steel—knew they had existed.

The year 1817 witnessed a more dramatic attempt to produce a striking match. A French chemist demonstrated to university colleagues his “Ethereal Match.” It consisted of a strip of paper treated with a compound of phosphorus that ignited when exposed to air. The combustible paper was sealed in an evacuated glass tube, the “match.” To light the match, a person smashed the glass and hastened to kindle a fire, since the paper strip burned for only the length of a breath. The French match was not only ethereal but ephemeral—as was its popularity.

Enter John Walker.

One day in 1826, Walker, the owner of an apothecary in Stockton-on-Tees, was in a backroom laboratory, attempting to develop a new explosive. Stirring a mixture of chemicals with a wooden stick, he noticed that a tear-shaped drop had dried to the stick’s tip. To quickly remove it, he scraped the drop against the laboratory’s stone floor. The stick ignited and the friction match was born in a blaze.

According to Walker’s journal, the glob at the end of his stick contained no phosphorus, but was a mixture of antimony sulfide, potassium chlorate, gum, and starch. John Walker made himself several three-inch-long friction matches, which he ignited for the amusement of friends by pulling them between a sheet of coarse paper—as alchemist Hennig Brandt had done two centuries earlier.

No one knows if John Walker ever intended to capitalize on his invention; he never patented it. But during one of his demonstrations of the three-inch match in London, an observer, Samuel Jones, realized the invention’s commercial potential and set himself up in the match business. Jones named his matches Lucifers. Londoners loved the ignitable sticks, and commerce records show that following the advent of matches, tobacco smoking of all kinds greatly accelerated.

Early matches ignited with a fireworks of sparks and threw off an odor so offensive that boxes of them carried a printed warning: “If possible, avoid inhaling gas. Persons whose lungs are delicate should by no means use Lucifers.” In those days, it was the match and not the cigarette that was believed to be hazardous to health.

The French found the odor of British Lucifers so repellent that in 1830, a Paris chemist, Charles Sauria, reformulated a combustion compound based on phosphorus. Dr. Sauria eliminated the match’s smell, lengthened its burning time, but unwittingly ushered in a near epidemic of a deadly disease known as “phossy jaw.” Phosphorus was highly poisonous. Phosphorus matches were being manufactured in large quantities. Hundreds of factory workers developed phossy jaw, a necrosis that poisons the body’s bones,

especially those of the jaw. Babies sucking on match heads developed the syndrome, which caused infant skeletal deformities. And scraping the heads off a single pack of matches yielded enough phosphorus to commit suicide or murder; both events were reported.

As an occupational hazard, phosphorus necrosis plagued factory workers in both England and America until the first nonpoisonous match was introduced in 1911 by the Diamond Match Company. The harmless chemical used was sesquisulfide of phosphorus. And as a humanitarian gesture, which won public commendation from President Taft, Diamond forfeited patent rights, allowing rival companies to introduce nonpoisonous matches. The company later won a prestigious award for the elimination of an occupational disease.

The Diamond match achieved another breakthrough. French phosphorus matches lighted with the slightest fiction, producing numerous accidental fires. Many fires in England, France, and America were traced to kitchen rodents gnawing on match heads at night. The Diamond formula raised the match’s point of ignition by more than 100 degrees. And experiments proved that rodents did not find the poisonless match head tempting even if they were starving.

Safety Match

. Invented by German chemistry professor Anton von Schrotter in 1855, the safety match differed from other matches of the day in one significant regard: part of the combustible ingredients (still poisonous) were in the head of the match, part in the striking surface on the box.

Safety from accidental fire was a major concern of early match manufacturers. However, in 1892, when an attorney from Lima, Pennsylvania, Joshua Pusey, invented the convenience he called a

matchbook

, he flagrantly ignored precaution. Pusey’s books contained fifty matches, and they had the striking surface on the

inside

cover, where sparks frequently ignited other matches. Three years later, the Diamond Match Company bought Pusey’s patent and moved the striking surface to the outside, producing a design that has remained unchanged for ninety years. Matchbook manufacturing became a quantity business in 1896 when a brewing company ordered more than fifty thousand books to advertise its product. The size of the order forced the creation of machinery to mass-manufacture matches, which previously had been dipped, dried, assembled, and affixed to books by hand.

The brewery’s order also launched the custom of advertising on match-book covers. And because of their compactness, their cheapness, and their scarcity in foreign countries, matchbooks were also drafted into the field of propaganda. In the 1940s, the psychological warfare branch of the U.S. military selected matchbooks to carry morale-lifting messages to nations held captive by the Axis powers early in World War II. Millions of books with messages printed on their covers—in Burmese, Chinese, Greek, French, Spanish, Dutch, Italian, and English—were dropped by Allied

planes behind enemy lines. And prior to the invasion of the Philippines, when native morale was at a wartime low, American aircraft scattered four million matchbooks bearing the promise: “I Shall Return—Douglas MacArthur.”

Today Americans alone strike more than five hundred billion matches a year, about two hundred billion of those from matchbooks.

Blender: 1922, Racine, Wisconsin

Popular legend has it that Fred Waring, the famous 1930s bandleader of the “Pennsylvanians,” invented the blender to liquefy fruits and vegetables for a relative suffering from a swallowing ailment.

Though this is not entirely correct, the bandleader did finance the development and marketing of a food liquefier named the Waring Blendor—which he insisted be spelled with an

o

to distinguish his machine from the competition. And it was the promotional efforts of his Waring Mixer Corporation, more than anything else in the 1930s, that acquainted the American public with the unique new blending device.

But Fred Waring never had a relative with a swallowing problem. And his interest in the blender was not to liquefy meals but to mix daiquiris, his favorite drink. In fact, the Waring Blendor, which sold in the ’30s for $29.95, was pitched mainly to bartenders.

The actual inventor of the blender (initially known as a “vibrator”) was Stephen J. Poplawski, a Polish-American from Racine, Wisconsin, who from childhood displayed an obsession with designing gadgets to mix beverages. While Waring’s blender was intended to mix daiquiris, Poplawski’s was designed to make malted milk shakes,

his

favorite drink. Opposite as their tastes were, their paths would eventually intersect.

In 1922, after seven years of experimentation, Poplawski patented a blender, writing that it was the first mixer to have an “agitating element mounted in the bottom of a cup,” which mixed malteds when “the cup was placed in a recess in the top of the base.”

Whereas Fred Waring would pitch his blender to bartenders, Stephen Poplawski envisioned his mixer behind the counter of every soda fountain in America. And Racine, Poplawski’s hometown, seemed the perfect place to begin, for it was home base of the Horlick Corporation, the largest manufacturer of the powdered malt used in soda fountain shakes. As Poplawski testified years later, during a 1953 patent litigation and after his company had been purchased by Oster Manufacturing, “In 1922 I just didn’t think of the mixer for the maceration of fruits and vegetables.”

Enter Fred Waring.

On an afternoon in the summer of 1936, the bandleader and his Pennsylvanians had just concluded one of their Ford radio broadcasts in Manhattan’s Vanderbilt Theater, when a friend demonstrated one of Poplawski’s blenders for Waring. This device, the friend claimed, could become a standard

feature of every bar in the country. He sought Fred Waring’s financial backing, and the bandleader agreed.

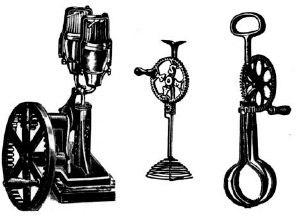

Mixers, c. 1890, that predate the blender and food processor. (Left to right) Magic Milk Shake Vibrator, Egg Aerater, Egg Beater

.

The mixer was redesigned and renamed, and in September of 1936 it debuted at the National Restaurant Show in Chicago’s Furniture Mart as the Waring Blendor. Highlighted as a quick, easy method for mixing frothy daiquiris and other iced bar drinks, and with beverage samples dispensed, Waring’s device attracted considerably more attention than Stephen Poplawski’s malted milk machine.

The Waring Blendor really caught the American public’s eye when the Ron Rico Rum Company launched a coast-to-coast campaign, instructing bartenders and home owners on the exotic rum drinks made possible by the blender. Ironically, by the early 1950s, blenders had established themselves so firmly in public and home bars and in restaurants that attempts to market them for kitchen use—for cake mixes, purees, and sauces—met with abysmal failure. To reeducate the homemaker, Fred Waring took to the road, demonstrating his blender’s usefulness in whipping up his own recipes for hollandaise sauce and mayonnaise. Still, the public wanted daiquiris.

Determined to entice the housewife, the Waring company introduced designer-colored blenders in 1955. An ice crusher attachment in 1956. A coffee grinder head in 1957. And the following year, a timing control. Sales increased. As did blender competition.

The Oster company launched an intensive program on “Spin Cookery,” offering entire meals developed around the blender. They opened Spin Cookery Schools in retail stores and mailed housewives series of “Joan Oster Recipes.”

In the late 1950s, an industry war known as the “Battle of the Buttons” erupted.

The first blenders had only two speeds, “Low” and “High.” Oster doubled the ante with four buttons, adding “Medium” and “Off.” A competitor

introduced “Chop” and “Grate.” Another touted “Dice” and “Liquify.” Another “Whip” and “Puree.” By 1965, Oster boasted eight buttons; the next year, Waring introduced a blender with nine. For a while, it seemed as if blenders were capable of performing any kitchen chore. In 1968, a housewife could purchase a blender with fifteen different buttons—though many industry insiders conceded among themselves that the majority of blender owners probably used only three speeds—low, medium, and high. Nonetheless, the competitive frenzy made a prestige symbol out of blenders (to say nothing of buttons). Whereas in 1948 Americans purchased only 215,000 blenders (at the average price of $38), 127,500,000 mixers were sold in 1970, and at a low price of $25 a machine.

Aluminum Foil: 1947, Louisville, Kentucky

It was the need to protect cigarettes and hard candies from moisture that led to the development of aluminum wrap for the kitchen.

In 1903, when the young Richard S. Reynolds went to work for his uncle the tobacco king R. R. Reynolds, cigarettes and loose tobacco were wrapped against moisture in thin sheets of tin-lead. After mastering this foil technology, in 1919 R.S. established his own business, the U.S. Foil Co., in Louisville, Kentucky, supplying tin-lead wraps to the tobacco industry, as well as to confectioners, who found that foil gave a tighter seal to hard candies than did wax paper. When the price of aluminum (still a relatively new and unproven metal) began to drop in the late ’20s, R. S. Reynolds moved quickly to adapt it as a cigarette and candy wrap.