Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things (18 page)

Read Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things Online

Authors: Charles Panati

Tags: #Reference, #General, #Curiosities & Wonders

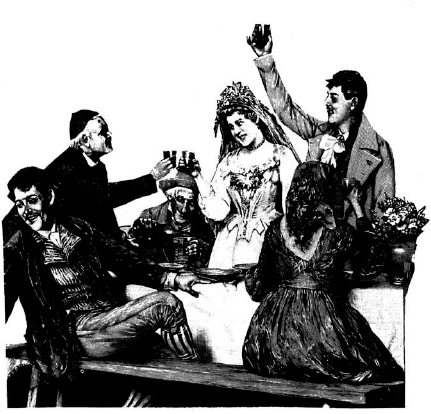

In summary: The Greeks drank to a friend’s health; the Romans flavored the drink with toast; and in time, the drink itself became a “toast.”

In the early eighteenth century, the custom of drinking a toast took a new twist. Instead of drinking to a friend present at a dinner, the toast was drunk to the health of a celebrated person, particularly a beautiful woman—whom

the diners might never have met. In

The Taller

of June 4, 1709, Sir Richard Steele mentions that British men were so accustomed to toasting a beautiful woman that “the lady mentioned in our liquor has been called a

toast

.” In Steele’s lifetime, a celebrated or fashionable Briton became known as the “toast of the town.”

Toasting arose as a goodwill gesture to prove a libation was not spiked with poison. In England, toasting a celebrated woman elevated her to being the “toast of the town

.”

In the next century, drinking toasts acquired such popularity in England that no dinner was complete without them. A British duke wrote in 1803 that “every glass during dinner had to be dedicated to someone,” and that to refrain from toasting was considered “sottish and rude, as if no one present was worth drinking to.” One way to effectively insult a dinner guest was to omit toasting him or her; it was, as the duke wrote, “a piece of direct contempt.”

Saying Grace

. The custom of offering a prayer before a meal did not originate as an expression of thanksgiving for the food about to be consumed. That came later—after the dawn of agriculture, when civilization’s first farmers began to pray to their gods for bountiful harvests.

In earlier times, nomadic tribes were not always certain of the safety of the food they found. Meat quickly rotted, milk soured, and mushrooms, berries, and tubers could often be poisonous. Since nomads changed habitats frequently, they were repeatedly confronted with new sources of food and determined their edibility only through trial and error. Eating could be hazardous to one’s health, resulting in cramps, fever, nausea, or death.

It is believed that early man initially prayed to his gods before eating to avert any deleterious influence the found or foraged food might have on him. This belief is reinforced by numerous later accounts in which peoples of the Middle East and Africa offered sacrifices to gods before a feast—not in thanksgiving but with deliverance from poisoning in mind. Later, man as a farmer grew his own crops and raised cattle and chickens—in short, he knew what he ate. Food was safer. And the prayers he now offered before a meal had the meaning we are familiar with today.

Bring Home the Bacon

. Though today the expression means either “return with a victory” or “bring home cash” —the two not being unrelated—in the twelfth century, actual bacon was awarded to a happily married couple.

At the church of Donmow, in Essex County, England, a flitch of cured and salted bacon used to be presented annually to the husband and wife who, after a year of matrimony, proved that they had lived in greater harmony and fidelity than any other competing couple. The earliest recorded case of the bacon award dates from 1445, but there is evidence that the custom had been in existence for at least two hundred years. Exactly how early winners proved their idyllic cohabitation is unknown.

However, in the sixteenth century, each couple that came forward to seek the prize was questioned by a jury of (curiously) six bachelors and six maidens. The couple giving the most satisfactory answers victoriously took home the coveted pork. The prize continued to be awarded, though at irregular intervals, until late in the nineteenth century.

Eat One’s Hat

. A person who punctuates a prediction with “If I’m wrong, I’ll eat my hat” should know that at one time, he or she might well have had to do just that—eat hat. Of course, “hat” did not refer to a Panama or Stetson but to something more palatable—though only slightly.

The culinary curiosity known as a “hatte” appears in one of the earliest extant European cookbooks, though its ingredients and means of preparation are somewhat vague. “Hattes are made of eggs, veal, dates, saffron, salt, and so forth,” states the recipe—but they could also include tongue, honey, rosemary, kidney, fat, and cinnamon. The book makes it clear that the concoction was not particularly popular and that in the hands of an

amateur cook it was essentially uneatable. So much so that a braggart who backed a bet by offering to “eat haste” had either a strong stomach or confidence in winning.

Give the Cold Shoulder

. Today this is a figurative expression, meaning to slight a person with a snub. During the Middle Ages in Europe, however, “to give the cold shoulder” was a literal term that meant serving a guest who overstayed his welcome a platter of cooked but cold beef shoulder. After a few meals of cold shoulder, even the most persistent guest was supposed to be ready to leave.

Seasoning

. Around the middle of the ninth century, when French was emerging as a language in its own right, the Gauls termed the process of aging such foods as cheese, wine, or meats

saisonner

. During the Norman Conquest of 1066, the French invaders brought the term to England, where the British first spelled it

sesonen

, then “seasoning.” Since aging food, or “seasoning” it, improved the taste, by the fourteenth century any ingredient used to enhance taste had come to be labeled a seasoning.

Eat Humble Pie

. During the eleventh century, every member of a poor British family did not eat the same food at the table. When a stag was caught in a village, the tenderest meat went to its captor, his eldest son, and the captor’s closest male friends. The man’s wife, his other children, and the families of his male friends received the stag’s “umbles” —the heart, liver, tongue, brain, kidneys, and entrails. To make them more palatable, they were seasoned and baked into an “umble pie.” Long after the dish was discontinued (and Americans added an

h

to the word), “to eat humble pie” became a punning allusion to a humiliating drop in social status, and later to any form of humiliation.

A Ham

. In the nineteenth-century heyday of American minstrelsy, there existed a popular ballad titled “The Hamfat Man.” Sung by a performer in blackface, it told of a thoroughly unskilled, embarrassingly self-important actor who boasted of his lead in a production of

Hamlet

.

For etymologists, the pejorative use of “ham” in the title of an 1860s theater song indicates that the word was already an established theater abbreviation for a mediocre actor vain enough to tackle the role of the prince of Denmark—or any role beyond his technical reach. “The Hamfat Man” is credited with popularizing the slurs “ham actor” and “ham.”

Take the Cake

. Meaning, with a sense of irony, “to win the prize,” the American expression is of Southern black origin. At cakewalk contests in the South, a cake was awarded as first prize to the person who could most imaginatively strut—that is, cakewalk. Many of the zany walks are known

to have involved tap dancing, and some of the fancier steps later became standard in tap dancers’ repertoires.

“Let Them Eat Cake

.”

The expression is attributed to Marie Antoinette, the extragavant, pleasure-loving queen of Louis XVI of France. Her lack of tact and discretion in dealing with the Paris proletariat is legend. She is supposed to have uttered the famous phrase as a retort to a beggar’s plea for food; and in place of the word for “cake,” it is thought that she used the word for “crust,” referring to a loaf’s brittle exterior, which often broke into crumbs.

Talk Turkey

. Meaning to speak candidly about an issue, the expression is believed to have originated from a story reported in the nineteenth century by an employee of the U.S. Engineer Department. The report states:

“Today I heard an anecdote that accounts for one of our common sayings. It is related that a white man and an Indian went hunting; and afterwards, when they came to divide the spoils, the white man said, ‘You take the buzzard and I will take the turkey, or, I will take the turkey and you may take the buzzard.’ The Indian replied, ‘You never once said turkey to me.’ “

Around the Kitchen

Kitchen: Prehistory, Asia and Africa

If a modern housewife found herself transported back in time to a first-century Roman kitchen, she’d be able to prepare a meal using bronze frying pans and copper saucepans, a colander, an egg poacher, scissors, funnels, and kettles—all not vastly different from those in her own home. Kitchenware, for centuries, changed little.

Not until the industrial revolution, which shook society apart and reassembled it minus servants, did the need arise for machines to perform the work of hands. Ever since, inventors have poured out ingenious gadgets—the dishwasher, the blender, Teflon, Tupperware, S.O.S. pads, aluminum foil, friction matches, the humble paper bag, and the exalted Cuisinart—to satisfy a seemingly unsaturable market. The inventions emerged to fill a need—and now fill a room in the house that has its own tale of origin and evolution.

In prehistoric times, man prepared food over an open fire, using the most rudimentary of tools: stone bowls for liquids, a mortar and pestle for pulverizing salt and herbs, flint blades for carving meat roasted on a spit. One of the earliest devices to have moving parts was the flour grinder. Composed of two disk-shaped stones with central holes, the grinder accepted grain through the top hole, crushed it between the stones, then released flour through the bottom hole.

In the Near East, the primitive kitchen was first modernized around 7000

B.C

. with the invention of

earthenware

, man’s earliest pottery. Clay pots and baking dishes then as now ranged in color from creamy buff to burnt

red, from ash gray to charcoal black. An item of any desired size or shape could be fashioned, fired by kiln, and burnished; and a wide collection of the earliest known kitchen pottery, once belonging to a Neolithic tribe, was unearthed in Turkey in the early 1960s. Bowls, one of the most practical, all-purpose utensils, predominated; followed by water-carrying vessels, then drinking cups. A clay food warmer had a removable bowl atop an oil lamp and was not very different in design from today’s models, fired by candles.

Terriers were trained as “spit runners” to relieve a cook from the tedium of hand-cranking a turnspit

.

Throughout the Greek and Roman eras, most kitchen innovations were in the realm of materials rather than usage—gold plates, silver cups, and glass bottles for the wealthy; for poorer folk, clay plates, hollowed rams’ horn cups, and hardwood jugs.

A major transformation of the kitchen began around

A.D

. 700. Confronted by the hardships of the Middle Ages, extended families banded together, life became increasingly communal, and the kitchen—for its food and the warmth offered by its fire—emerged as the largest, most frequented room in the house.

One of the valued kitchen tools of that time was the turnspit. It was to survive as the chief cooking appliance for nearly a thousand years, until the revolutionary idea in the late 1700s of roasting meat in an oven. (Not that the turnspit has entirely disappeared. Many modern stoves include an electrically operated rotary spit, which is also a popular feature of outdoor barbecues.)

In the turnspit’s early days, the tedious chore of hand-cranking a roast led to a number of innovations. One that today would incense any animal lover appeared in England in the 1400s. A rope-and-pulley mechanism led from the fired spit to a drum-shaped wooden cage mounted on the wall. A small dog, usually a terrier, was locked in the cage, and as the dog ran, the cage revolved and cranked the spit. Terriers were actually trained as

“spit runners,” with hyperactive animals valued above others. Gadgets were beginning to make their mark.