Read Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure Online

Authors: Tim Jeal

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Adventure, #History

Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure (25 page)

Speke certainly made no secret of finding the wives of courtiers attractive. On a buffalo-shoot he ‘commenced flirtations with M’tesa’s women, much to the surprise of everyone’. He also offered to carry several wives of courtiers across a stream piggyback fashion. The most beautiful one was especially eager to find out,

what the white man was like, [and] with an imploring face

and naked breasts

held out her hands in such a

voluptuous,

captivating manner that though [Speke] feared to draw attention by waiting any longer [to cross], could not resist compliance … ‘Woh, woh!’ said the Kamraviona ‘What wonders will happen next?’

7

Speke found it wonderfully gratifying that most women at court were

‘charmed with the beautiful appearance of myself’.

But to his grief, this was not how Méri – whom he described as

‘my beautiful Venus’ -

saw him. Quite often she refused to speak to him, or go for walks, or do anything ‘but lie at full length all day long … lounging in

the most indolent manner’.

Provoked, he said, beyond endurance by her indifference, Speke

‘spent the next night in taming the silent shrew’.

8

Though this sounds suspiciously like rape, it should be remembered that in Shakespeare’s

Taming of the Shrew

the final proof of the success of Petruchio’s ‘taming’ of Kate was her ultimate willingness to go

to bed with him, without being coerced. But whether Speke forced himself on Méri, or whether she consented, or whether indeed his taming involved sex at all, is beyond knowing. What

is

certain is that his feelings for the girl deepened; and by the end of the month when he was separated from her – while accompanying Mutesa on a lengthy hippo-hunt – he found himself dreaming of Méri at night, and to a lesser extent of Kahala, and

‘looking fondly forward to seeing what change would have been produced by this forcible separation of one week on those I loved, though they loved not me’

.

9

On his return in early May, Méri tried to persuade him to give her a goat as a gift – although really she meant to pass it on to her favourite

nganga

(witch doctor). Even when Speke had rumbled her, she kept on nagging for the goat. ‘Oh

God! Was I then a henpecked husband?’

he complained. On learning that Méri had invited the

nganga

into their hut during his absence, a jealous Speke threatened to beat the man. At this point, Méri shattered him by begging to be beaten instead.

This touching appeal nearly drove my judgment from me, but as Méri showed neither love nor attachment for me

… [and my]

offers

[were]

indifferently accepted without grace, which broke my sleep and destroyed my rest… I therefore dismissed her, and gave her as a sister and free woman to Uledi … I then rushed out of the house with an overflowing heart and walked hurriedly about till after dark, when returning to my desolate abode, turned supperless into bed, but slept not one wink reflecting over the apparent cruelty of abandoning one, who showed so much maidenly modesty when first she came to me, to the uncertainties of this wicked world

.

10

So Speke, who has typically been represented as incapable of love, fell painfully for a young African woman, and was made wretched by her refusal to reciprocate. A week later, Méri came to see him, saying that she had been ill since their row, and asked, with tears in her eyes, to be taken back. Speke told her she had been very wrong

‘to fight with her lord’,

to which she replied that

‘the only fighting she knew anything about was the fight of love’

.

11

But though Speke wanted to persuade himself

that her unyielding behaviour had been

‘the fight of love’,

he failed. She could only come back he decided, if she showed evidence of being emotionally involved. Sadly, what she told him next convinced him that the situation was hopeless.

‘Her luck was very great once,’

she explained.

‘She was Sunna’s wife, the N’yamasore’s

[Queen Mother’s]

maid, then his

[Speke’s]

wife; so she

[had]

never lived in a poor man’s house since she was a child; and now she wished to return

[to Speke]

so that she might die in the favours of a rich man.’

.

12

Unsentimental honesty was not at all what the romantic Speke had wanted to hear, and he was clearly incapable of considering things from the point of view of a young woman brought up in an African feudal society, who had offered to be his wife on terms she considered satisfactory.

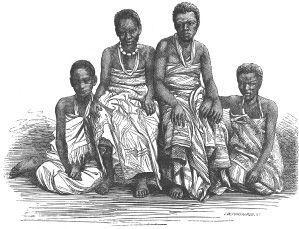

Kahala and other young Baganda women. There is no known image of Méri.

Grieving over the loss of Méri (as he had wished her to be), he stopped visiting the Queen Mother, who rebuked him angrily for ignoring her after she had been considerate enough to have

‘given him such a charming damsel’.

Speke noted in his journal that

‘she little thought as she was speaking

[that]

she was driving an arrow into my heart’

.

13

When he finally realised that he would never be close to Méri in the way he wanted, Speke gave the young woman some valedictory gifts:

In token I ever loved her and could do so now … a black blanket as a sign of mourning that I never could win her heart; a bundle of gundu

[giraffe-hair ankle rings inter-woven with brass wire]

in remembrance of her once having asked for them … and I

[had]

thought they would ill-become her pretty ankles. Lastly there was a packet of tobacco in proof of my forgiveness, though she had almost broken my heart; and for the future I only hoped she might live a life of happiness with people of her own colour as she did not like me because she did not know my language to understand me

.

14

Because Méri had described herself as Speke’s wife, and he had referred to himself as her husband, it seems likely that they were sexual partners, but whatever had passed between them, his disappointed love was clearly genuine – although given the language barrier, sexual attraction must always have been the major component. But the usual picture of Speke as a selfish and insensitive misogynist does not tally with his tender feelings for Méri, and with the fact that his sense of honour prevented him from continuing to treat her as ‘his wife’, as she would gladly have allowed him to do if, as she had wished, he had taken her back. With no experience of romantic love – in the European sense – Mutesa and the Queen Mother had expected Speke to use Méri for his pleasure regardless of her feelings. For the most part, later adventurers and settlers would have few moral qualms about exploiting African women. There is a rumour, which surfaces from time to time, that Speke impregnated Méri.

15

While this is possible, the fact that they were together so short a time militates against it. Speke would leave Mengo in July about three months after he described ‘taming’ his ‘shrew’ in April, so if she had been impregnated she would have known it by then, and would have had no reason not to tell him. His journal is remarkably unbuttoned in its manuscript version, and

yet there is no mention of a pregnancy. But in the end there can be no certainty either way.

At first, in his anger at not being loved in the way he wanted, Speke handed Méri to Uledi and his wife, Mhmua, to be her keepers. Though he described her as ‘a free woman’ and ‘a sister to Mhmua’, the latter sometimes tied Méri to her wrist to stop her running away.

16

A few weeks later, Speke evidently felt so uneasy about her situation that he offered to try ‘to marry her to one of Rumanika’s sons, a prince of her own breed’. But Méri rebuffed his well-meaning efforts.

17

Until his disappointment in love, Speke had greatly enjoyed his privileged status at court, as well as his close relationships with individual Baganda from the king and his mother at the top, right down to pages and servants. In fact his enthusiastic participation in daily events, and his easy manner with African women, differentiated him from Burton, Baker, Grant and Livingstone, all of whom maintained (in their diaries at least) a much greater distance.

18

But coinciding with his loss of Méri came a steadily increasing awareness of the darker side of Mutesa’s nature, which began to mar the pleasure he had once taken in being part of Baganda high society. On one occasion the king flew into a rage with a formerly favoured wife, whom Speke had always found charming. For nothing more wicked than offering her lord and master some fruit – when it had actually been the role of a particular court functionary to feed him – she was dragged away to be executed for this minor breach of etiquette ‘crying in the names of

Kamraviona

and

Mzungu,

for help and protection’. As the

kabaka

’s other wives clung to his knees, begging him to be merciful, the king began beating the condemned woman over the head with a stick. This was too much for Speke, who ‘rushed at the king, and staying his uplifted arm, demanded from him the woman’s life’. Well aware that he ‘ran imminent risk of losing [his] own life’, Speke was thankful when ‘the novelty of interference made the capricious tyrant smile, and the woman was instantly released’. A royal page who misinterpreted a message from Speke to the king was less fortunate and had his

ears cut off for not listening more attentively.

19

But far worse than any of this was the

kabaka

’s punishment of a wife who had run away from a cruel husband, and of the elderly man who had bravely given her shelter. Both were sentenced to be given food and water for several weeks, while they were ‘dismembered, bit by bit, as rations for the vultures, every day, until life was extinct’. What horrified Speke was Mutesa’s ‘total unconcern about the tragedy he had enacted’. As soon as the condemned man and woman had been ‘dragged away boisterously … to the drowning music of the

milélé

and drums’, the king turned cheerfully to Speke: ‘Now, then, for shooting

Bana;

let us look at your gun.’

20

But despite his revulsion, Speke could not afford to offend Mutesa or refuse to show him his picture books, or shoot with him, or offer him medical treatment, if he requested it. He also felt obliged to obey the king when he asked for his portrait to be made. In the pencil and water colour sketch, which Speke produced of him, the king is naked, ‘preparing for his blister’: an archaic procedure, by which fluid was drawn from the part of the body being treated. Mutesa’s expression is inscrutable, and despite the artist’s limitations, the king’s body looks slim and graceful, although his genitals are drawn smaller than life size, as in Greek works of art.

21

Given their earlier conversation on the subject of what made a penis the ideal size, it seems unlikely that the picture pleased the king. (

See colour plates.)

On 14 May, Mabruki, who had been led to Bunyoro by Baganda guides, returned with the thrilling news that although Petherick had not yet arrived in King Kamrasi’s country, his party was still at Gani. The fact that one of the two white men was said to be bearded, seemed to guarantee that Petherick himself was present. Mabruki explained that Baraka and Uledi, who had been sent to Bunyoro from Karagwe in late January, were still being detained by Kamrasi, and were thus unable to leave for Gani. This was extremely frustrating for Speke. Meanwhile Grant, who had hoped to survey the lakeside on his way from Karagwe to Buganda, had sent ahead a message to say he was

still crippled by his ulcerated leg and was being carried and was therefore unable to make observations. While Speke longed for Grant’s arrival so they could leave for the Nyanza’s outlet,

en route

to Bunyoro and Gani, Mutesa remained more interested in shooting than in the white man’s plans. The day after Mabruki reappeared, the

kabaka

hit and killed a large adjutant bird or great stork (

leptopilos)

and ‘in ecstasies of joy and excitement, rushed up and down the potato-field like a mad bull … Whilst the drum beat, the attendants all woh-wohed, and the women rushed about lullooing and dancing’.

22

Grant finally arrived on 27 May 1862, after a period of four months’ separation from Speke. They were, in Grant’s words, ‘so happy to be together again, and had so much to say, that when the pages burst in with the royal mandate that his Highness must see me tomorrow, we were indignant at the intrusion’. At his first audience, Grant was as impressed by Mutesa’s person and clothing as Speke had been, but it was not long before ‘a shudder of horror crept over [him]’. As the audience ended, two young women, who had had the temerity to smile at the explorers, were dragged away by the executioner. ‘Could we have been the cause of this calamity?’ agonised Grant, ‘and could the young prince with whom we had conversed so pleasantly have the heart to order the poor women to be put to death?’ He would know the answer long before hearing the cries of people being tortured whenever he passed the hut of Maula, Mutesa’s chief detective. Grant admired Speke for having the courage to intervene from time to time. Once, his friend even succeeded in securing the release of the executioner’s own son, who had been condemned to death.

23