Read Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure Online

Authors: Tim Jeal

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Adventure, #History

Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure (22 page)

He might perhaps have been able to inspire them, if his health had been better; but his cough was now so bad that he had to sleep propped up in a sitting position. His heart felt ‘inflamed … pricking and twingeing [sic] with every breath’; his left arm was half-paralysed, his nostrils full of mucus, and his body was racked with pain from his shoulder blades down to his spleen and liver. In such a frail condition all he could do was repeat that he had no intention of going to Lumeresi’s

boma.

But he knew he would have to give in if his men went on refusing to obey his orders. ‘This was terrible: I saw at once that all my difficulties in Sorombo [with Makaka] would have to be gone through again.’

41

Speke’s first ten days as the involuntary guest of Lumeresi -really he was his prisoner – were a nightmare. The chief warned him that he would never be allowed to leave until he had parted with two

dèolès-

the richly embroidered cloaks he was saving for the kings of Karagwe and Buganda. Three weeks passed and Speke was still failing to negotiate

hongo

payments satisfactory to his persecutor. At this ill-starred moment, Mfundi, who had robbed him shortly after his first departure from Kazeh, appeared in the village and declared that the road to Usui was closed,

and that he personally had burned down all the villages on the path. On hearing this, Speke’s new guides begged to be released, since they ‘would not go a step beyond this’. Eventually, after a supreme effort of persuasion, Speke managed to get Bui, the bravest of the guides, to agree to come with him to Usui as soon as Lumeresi had agreed the

hongo

payment. Overjoyed by Bui’s change of heart, Speke had his chair placed under a tree and smoked his first pipe since he had fallen ill. ‘On seeing this, all my men struck up a dance, which they carried on throughout the whole night.’

None of this had any effect on Lumeresi, who had been bullying the explorer for a month now, and was as determined as ever to have a finely embroidered silk cloak. In the end, Speke had no choice but to give him the

dèolè

he had saved for King Rumanika. Not even that was enough and Lumeresi insisted on his giving him double the amount of brass wire and cloth he had originally asked for. The chief’s drums were beaten at last, so a poorer Speke was free to go, but now Speke found that his guides, Bui and Nasib, who also doubled as interpreters, had fled.

The shock almost killed me. I had walked all the way to Kazeh and back again [a round trip of over 200 miles] for these two men to show mine a good example – had given them pay and treble rations, the same as Bombay and Baraka – and yet they chose to desert. I knew not what to do, for it appeared that do what I would, we would never succeed; and in my weakness of body and mind, I actually cried like a child.

42

Speke’s ability to negotiate calmly, often for weeks at a time, with a succession of chiefs who clearly wished to rob him of everything, was remarkable. This, coupled with his unceasing efforts – in the face of serious illness – to keep his caravan together and find new porters (walking many hundreds of miles in the process) marked him out as a great explorer.

Only a dozen miles to the south, Grant, for a change, was suffering even greater problems. A local chief sent 200 men armed with spears and bows and arrows rampaging through his camp, stealing whatever came to hand. Only one of Grant’s men

stood at bay, with his rifle at full cock, in defence of his load; the rest fled. Grant himself had the terrifying experience of having the tips of assegais pressed against his chest. He was only too well aware of the danger he was in, since a few days earlier he had witnessed the execution of a man, whose genitals had been set on fire before he had been stabbed to death. But Grant was not harmed, and later that day, fifteen of fifty-six loads were returned – the chief evidently having felt that if his neighbouring chiefs had heard that he had left nothing for them to extract from the white man, he could expect to be attacked.

43

Speke was appalled when told what had happened, but he was saved from despair by the arrival at Lumeresi’s village of four men sent by Rumanika and Suwarora to say that they were eager to see him and that he should not believe anything he might have heard about them harming caravans. Lumeresi, however, sent these men away calling them frauds, and in the end only agreed to help Speke find porters for the journey north when Suwarora sent some more men bearing his mace – a long rod of brass decorated with charms. Lumeresi had remorselessly milked Speke from 23 July to 6 October 1861, when he and Grant, who had very recently joined him, were finally able to get away.

44

Travelling north once more towards Usui, the dried-up countryside began to change for the better. Before, the only shade had been offered by the occasional fig or mango tree, but now the endless tracts of leafless scrub and burned grass were giving way to mixed woodland and green hills crowned with granite outcrops. In the valley bottoms, they walked through ‘pleasant undulations of tall soft grass’, and crossed streams destined for the distant Nyanza. Speke would indicate on his map that he was rarely nearer to the lake than sixty miles. His desire not to encounter more chiefs than was absolutely necessary probably accounts for his failure to visit the lake at intervals to establish whether it was a single sheet of water or several.

Close to Chief Suwarora’s stronghold, they dropped down into a valley ‘overhung by delightfully wild rocks and crags’, which Grant declared to be like ‘the echoing cliffs over the Lake

of Killarney’.

45

Unfortunately, the chief and his henchmen were not to prove as delightful as the country they inhabited. Despite their earlier promises to behave differently from Lumeresi and Makaka, they fleeced Speke in exactly the same way and left him and Grant to pitch their tents in a place where rats, fleas and vicious ants made their nights a misery. Grant described Suwarora himself as ‘a superstitious creature, addicted to drink, and not caring to see us, but exacting through his subordinates the most exorbitant tax we had yet paid’.

46

Speke felt slightly happier about his situation when he met an Arab trader, Masudi, who had taken over a year to travel the 150 miles from Kazeh to Suwarora’s

boma

at Usui and

en route

had been obliged to pay even more than he and Grant had done. Since leaving Kazeh, Speke and Grant had been on the road a mere eight months. Yet, while it seemed easily explicable that slave-trading Arabs should be ill-treated, it struck them as extraordinary that people who had never seen Europeans before, or ever been harmed by them, should treat them in a similar way.

Left to wait for weeks outside the chief’s fenced enclosure, in patchy jungle with no shady trees, Speke and his men were robbed even by ordinary villagers – the most audacious theft being the abduction of two women attached to the caravan. Most of Speke’s captains had acquired additional wives and concubines during the journey. The thieves had torn off the women’s clothes, hurrying them away ‘in a state of absolute nudity’. This was too great an insult to be endured, and Speke gave orders that the next thief should be fired at. The following night an intruder was indeed shot at close range. ‘We tracked him by his blood, and afterwards heard he had died of his wound.’

47

He and Grant finally escaped the clutches of Suwarora on 15 November 1861 and began their march to Karagwe – a region which Grant would soon compare, rhapsodically, with the English Lake District. For Speke it was ‘truly cheering’ to reflect that they ‘now had nothing but wild animals to contend with before reaching Karagwe’.

48

By the end of November they had reached a country of grassy hills, most of them 5,000 feet

tall, and from the top of one called Weranhanjè, they saw far below them a beautiful lake, which Speke and Grant thought very like England’s Lake Windermere. On a plateau overlooking the water was the palace enclosure, shielded by a screen of trees. This kingly residence was on a larger scale than anything they had yet seen, with many huts and interlinked courtyards. To honour the king, Speke ordered his men to fire a volley outside the palace gate. To their surprise, Rumanika invited them in at once, without obliging them to wait for weeks for the honour of an audience.

49

From their first sight of him, both explorers were captivated. Rumanika, said Grant, was ‘the handsomest and most intelligent sovereign they had met with in Africa. He stood six foot two inches in height, and his countenance had a fine, mild, open expression’.

50

Speke described the first greetings of the king as being ‘warm and affecting … [and] delivered in good Kiswahili’. It was clear from the start that the king felt himself fortunate to meet these strangers from afar and had no plans to fleece them. In fact he would rebuke his brother when he begged for a gun, and would never demand anything for himself, although Speke and Grant would voluntarily give him many presents. ‘He had been alarmed he confessed, when he had heard we were coming to visit him, thinking we might prove some fearful monsters, that we were not quite human, but now he was delighted beyond all measure by what he saw of us.’ He asked intelligent questions, such as whether ‘the same sun we saw one day appeared again, or whether fresh suns came every day’. But while Speke answered this question in a straightforward and factual way, when Rumanika asked him to explain the decline of kingdoms (it pained the king that Karagwe no longer ruled over Burundi and Rwanda) the explorer told him that Britain maintained its power in the world because Christianity gave a sense of moral entitlement. In the spirit of wishing to share this bounty, Speke offered to take one of the king’s children back to England to be educated in a Christian school, so that he could return to Karagwe to impart to others what he had learned. In contradiction of what he had

said earlier about Christianity, Speke went on to say that science was the branch of knowledge best adapted to increase a nation’s wealth, and he cited the impact of the electric telegraph and the steam engine. Rumanika’s intelligence and kindness, coming after so much bullying and disrespect, made Speke feel much more optimistic about the next and most crucial phase of his journey.

51

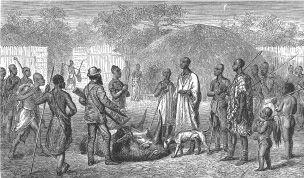

Speke and Grant present Rumanika with a rhinoceros’ head.

Speke and Grant celebrated Christmas at Rumanika’s court with his athletic sons and amazingly fat daughters, who were force-fed with milk and beef-juice until they became almost spherical, as was the fashion for women at court. Just as the crinoline in Europe demonstrated that a ‘lady’ did not work, these princesses were showing that they too led ornamental lives and had parents who could afford to feed them prodigiously. In exchange for showing one of the princesses his bare arm, Speke persuaded this young woman, who ‘was unable to stand except on all fours’, to allow him to measure her. The circumference of her upper arm was an amazing two feet, and that of her thigh almost three feet. Her rolls of flesh made him think of gigantic puddings.

52

Early in the New Year of 1862, the explorers received news which, wrote Speke, ‘drove us half wild with delight for we fully believed Mr Petherick was indeed on his road up the Nile, endeavouring to meet us’. The members of a diplomatic mission, sent by Rumanika some months earlier to Bunyoro (to the north of Buganda), had just returned, bringing news that foreigners in boats had arrived in Gani, north-east of Bunyoro. These foreigners had apparently been driven off to the north. Because Speke was convinced by this intelligence that Petherick and his party had just failed to get through, he wrote the Welshman a letter of encouragement, which was taken north by Baraka, Uledi and a small bodyguard provided by Rumanika. On 7 January an Indian ivory trader called Juma arrived in Karagwe with news that King Mutesa of Buganda was sending some officers to greet Speke and Grant and escort him back to his kingdom.

Just when their final push towards the source of the Nile seemed to be beginning, Grant’s health threatened his participation. His right leg, above the knee, had become stiff, swollen and alarmingly inflamed. He could neither walk nor leave his hut. The intense pain was only eased by his making incisions to release the fluid. Yet fresh abscesses would form within days. In his desperate situation, he was ready to try any cure suggested by the locals, including a cow-dung poultice and having a paste like gunpowder rubbed into the cuts. One theory was that he had been bitten by a snake when sleeping. It seems more likely that he was suffering from a bacterial infection of the deep tissues, which today would be treated with antibiotics. Although Grant did not know it, months of suffering lay ahead while his immune system rallied to fight the infection.

53

So when, on 10 January, Maula, a royal officer from Buganda, strode into Rumanika’s palace enclosure, followed by a smartly dressed escort of men, women and boys, and announced that Kabaka Mutesa was eager to see the white men, the uncomplaining Grant had to be left behind. He seemed content with Speke’s assurances that they would be re-united as soon as his leg improved. Rumanika had warned both men that Mutesa never allowed sick people to enter his country.