Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (97 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

5.

Test tone at the wrists and elbows by moving the joints at varying velocities.

6.

Assess power next.

a.

Shoulder:

•

abduction (C5, C6): tell the patient to abduct his arms with the elbows flexed and not to let you push them down

•

adduction (C6–C8): tell him to adduct his arms with the elbows flexed and not to let you separate them.

b.

Elbow:

•

flexion (C5, C6): tell him to bend his elbow and pull so as not to let you straighten it

•

extension (C7, C8): tell him to bend his elbow and push so as not to let you bend it.

c.

Wrist:

•

flexion (C6, C7): tell him to bend his wrist and not to let you straighten it

•

extension (C7, C8): tell him to straighten his wrist and not to let you bend it.

d.

Fingers:

•

extension (C7, C8): tell him to straighten his fingers and not to let you push them down

•

flexion (C7, C8): tell him to squeeze two of your fingers

•

abduction (C8, T1): tell him to spread out his fingers and not to let you push them together.

•

Grade the power (p. 440).

7.

Test for an ulnar lesion (loss of finger abduction and adduction) and a median nerve lesion (loss of thumb abduction) (p. 445).

8.

Examine the reflexes:

a.

biceps (C5, C6) – biceps muscle

b.

triceps (C7, C8) – triceps muscle

c.

supinator (C5, C6) – brachioradialis muscle (elbow flexion)

d.

inverted supinator jerk – when tapping the lower end of the radius, elbow extension and finger flexion are the only response; associated with an absent biceps and exaggerated triceps jerk, this indicates an intraspinal lesion compressing the spinal cord and nerve roots at C5, C6

e.

finger (C8) – normally, slight flexion of all fingers occurs (not routine).

9.

Assess coordination with finger–nose testing and look for dysdiadochokinesis and rebound (p. 458).

Motor weakness can be caused by an upper motor neurone lesion, lower motor neurone lesion, neuromuscular junction disorder or myopathy. If there is evidence of a lower motor neurone lesion, consider anterior horn cell, nerve root and brachial plexus lesions, peripheral nerve lesions or a motor peripheral neuropathy.

SENSORY SYSTEM

Examine the sensory system after motor testing because this can be time-consuming (and confusing, even when assessed by experts).

1.

First test the spinothalamic pathway (pain and temperature). Use a new blunt neurology pin. One candidate accidentally pricked his own finger during the examination with a sharp pin. By the time he stopped bleeding his short case time was up. (In case you believe this might be a good ploy, the candidate failed.)

2.

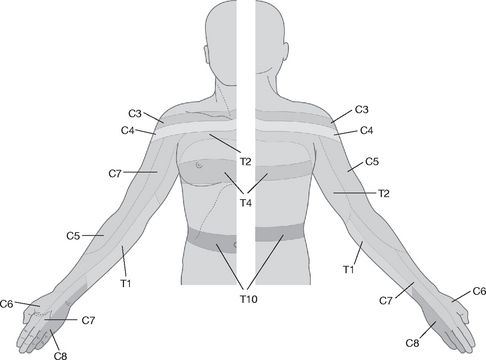

Demonstrate to the patient the sharpness of the pin on the anterior chest wall or forehead. Then ask him to close his eyes and tell you if the sensation is sharp or dull. Start proximally and test each dermatome. As you are assessing, try to fit any sensory loss into dermatomal (cord or nerve root lesion) (see

Fig 16.94

), peripheral nerve, peripheral neuropathy (glove) or hemisensory (cortical or cord) distribution. Also remember that ‘cape’ sensory loss (neck, shoulders and arms) suggests syringomyelia, whereas ‘shield’ sensory loss (front of the chest) may occur with syphilis. It is not usually necessary to test temperature perception in the examination.

FIGURE 16.94

Dermatomes of the upper limb and trunk.

3.

Next test the posterior column pathway (vibration and proprioception). Use a 128-hertz tuning fork to assess vibration sense. Place this when vibrating on the ulnar head at the wrist when the patient has his eyes closed and ask whether he can feel it. If so, ask him to tell you when the vibration ceases and then stop the vibration. If the patient has deficient sensation, test at the elbow, then the shoulder. Test both arms.

4.

Examine proprioception first with the DIP joint of the index finger. When the patient has his eyes open, grasp his distal phalanx from the sides and move it up and down to demonstrate, then ask him to close his eyes and repeat the manoeuvres. Normally, movement through even a few degrees is detectable and he can tell whether it is up or down. If there is an abnormality, proceed to test the wrist and elbows similarly.

HINT

Proprioceptive loss may be subtle. A normal person can detect movement and usually direction changes of 1 or 2°. Begin with small joint movements.

5.

Test light touch with cotton wool. Touch the skin lightly in each dermatome. Do NOT stroke!

6.

Feel for thickened nerves – ulnar at the elbow, median at the wrist and radial at the wrist – and feel the axillae if there is evidence of a plexus lesion. Do not forget to mention any scars that may be present. Finally, examine the neck movements, if relevant, and look for surgical scars in the front and back of the neck and in the axillae.

7.

To confirm a diagnosis, it may be necessary to examine further afield. Ask the examiners whether you can do this. For example, if there is evidence of motor neurone disease, assess the lower limbs, as well as the tongue. If there is evidence of a C5, C6 root lesion, assess the lower limbs for an upper motor neurone lesion and the neck for cervical spondylosis.

Shoulder girdle examination

‘This 48-year-old woman has had difficulty lifting objects above her head. Please examine her shoulder girdle.’

HINT

This introduction is often used for facio-scapulo-humeral (FSH) muscular dystrophy. A careful inspection of the face will reveal wasting of the masseter and temporalis muscles, among others.

Method

This is likely to be a muscular dystrophy or a root lesion. Proceed by inspecting each muscle, palpating its bulk and testing function as follows.

1.

From the back:

a.

trapezius (XI, C3, C4) – ask the patient to elevate her shoulders against resistance and look for winging of the upper scapula

b.

serratus anterior (C5–C7) – ask her to push her hands against the wall and look for winging of the lower scapula

c.

rhomboids (C4, C5) – ask her to pull both shoulder blades together with her hands on her hips

d.

supraspinatus (C5, C6) – ask her to abduct her arms against resistance and begin with her arms less than 15° from her sides

e.

infraspinatus (C5, C6) – ask her to rotate her upper arms externally against resistance with her arms at her side

f.

teres major (C5–C7) – ask her to rotate her upper arms internally against resistance

g.

latissimus dorsi (C7, C8) – ask her to cough and palpate on both sides.

2.

From the front:

a.

pectoralis major, clavicular head (C5–C8) – ask the patient to lift her upper arms above the horizontal and push them forward

b.

pectoralis major, sternocostal part (C6–T1) and pectoralis minor (C7) – ask her to adduct her upper arms against resistance

c.

deltoid (C5, C6) (and circumflex nerve) – ask her to abduct her arms against resistance, but begin with her arms more than 15° from her sides.

3.

Go on to look for sensory changes, which will be absent if this is a muscular dystrophy.

HINT

If FSH is suspected (facial muscle wasting and winging of the scapulae), look for foot drop and then test for facial weakness (inability to close the eyes tightly, whistle or puff out the cheeks).

Lower limbs

‘This 60-year-old man has had difficulty walking. Please examine his lower limbs.’

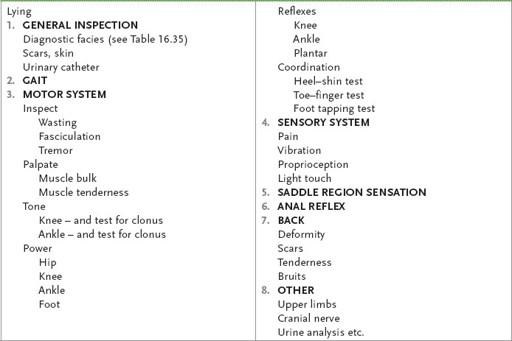

Method (see

Table 16.55

)

Table 16.55

Lower limb neurological examination

1.

Test the gait first. Ask the examiners whether this is possible – sometimes the patient may be unable to walk. If the patient can walk, ask him to walk across the room, turn around and walk back. If he looks to be in difficulty, ask the proctor attendant to help. Ask the patient to try heel-to-toe walking (for cerebellar disease) and then try standing and then walking on toes and heels (for an S1 or L4/L5 lesion, respectively). Ask him to squat and stand (for proximal myopathy).

HINT

Specific testing of gait should help you decide whether there is an ataxic or high stepping gait (cerebellar or proprioceptive problems) or muscle weakness (proximal or distal, or both).

2.

Note the patient’s general appearance. Especially look for upper limb girdle wasting and the presence of a urinary catheter. Look for pes cavus. Look around the room for a walking stick or frame and special shoes.

3.

Have the patient lie in bed with the legs entirely exposed. Place a towel over the groin. Look at the patient’s back for scars.

4.

Look for muscle wasting and fasciculation. Note any tremor. Feel the muscle bulk of the quadriceps and run your hand up each shin, feeling for wasting of the anterior tibial muscles.

5.

Test tone at the knees and ankles.

6.

Test clonus at this time. Warn the patient first. Push the patella sharply downwards. Sustained rhythmical contractions indicate an upper motor neurone lesion. Also test the ankle by sharply dorsiflexing the foot with the knee bent and the thigh externally rotated. Always test both sides!

7.

Assess power next.

a.

Hip:

•

flexion (L2, L3): ask the patient to lift up his straight leg and not let you push it down (having placed your hand above his knee)

•

extension (L5, S1, S2): ask him to keep his leg down and not let you pull it up

•

abduction (L4, L5, S1): ask him to abduct his legs and not let you push them together

•

adduction (L2, L3, L4): ask him to keep his legs adducted and not let you pull them apart.

b.

Knee:

•

flexion (L5, S1): ask him to bend his knee and not let you straighten it

•

extension (L3, L4): with the knee slightly bent, ask him to straighten the knee and not let you bend it.

c.

Ankle:

•

plantar flexion (S1): ask him to push his foot down and not let you pull it up

•

dorsiflexion (L4, L5): ask him to bring his foot up and not let you push it down

•

eversion (L5, S1): ask him to evert his foot against resistance; loss of this may also indicate a common peroneal (lateral popliteal) nerve palsy

•

inversion (L5): ask him to invert his plantar flexed foot against resistance.

8.

Elicit the reflexes:

a.

knee (L3, L4) – quadriceps muscle

b.

ankle (S1, S2) – calf muscle

c.

plantar response (S1).

9.

Test coordination with the heel–shin test, toe–finger test and tapping of the feet (p. 458).

10.

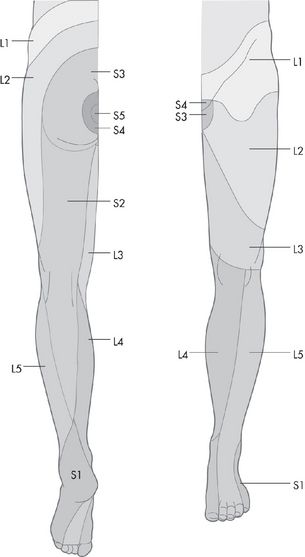

Examine the sensory system as for the upper limbs: pin prick, then vibration and proprioception, and then light touch (see

Fig 16.95

).