Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (36 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

Investigations

Management of cirrhosis depends on the aetiology, morphology and hepatic function. It is important to make a diagnosis and exclude potentially reversible causes of further liver deterioration.

1.

Liver function tests

. These should be used to confirm abnormalities, follow progress and give an idea of prognosis (particularly a low albumin level and prolonged INR). An aspartate aminotransferase (AST) to alanine aminotransferase (ALT) ratio of >2.0 suggests alcoholic liver disease.

2.

Full blood count

. This is helpful because anaemia may be caused by chronic disease, blood loss, folate deficiency, bone marrow depression, hypersplenism, haemolysis or sideroblastic anaemia. Round macrocytes are common in alcoholics. Remember that leucopenia and thrombocytopenia occur in hypersplenism. A low platelet count in the setting of chronic liver disease suggests cirrhosis.

3.

Renal function tests

. These are important to exclude the hepatorenal syndrome. Hyponatraemia is common in cirrhosis.

4.

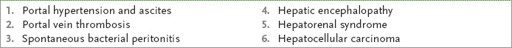

Ascitic tap

(see

Tables 7.10

and

7.11

). Rule out spontaneous bacterial peritonitis if ascites is present (>250/mm

3

polymorphs).

Table 7.10

Causes of ascites and interpretation of ascitic fluid studies

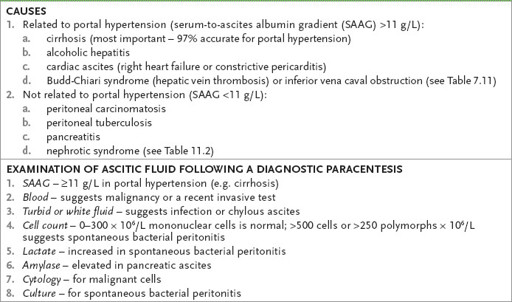

Table 7.11

Budd-Chiari syndrome

5.

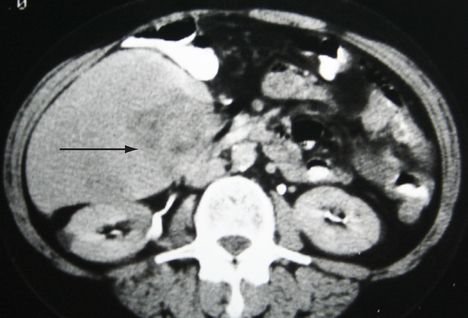

Ultrasound or abdominal CT scan

(see

Fig 7.12

). This may help exclude biliary obstruction and infiltration. The texture of the liver may suggest infiltration (e.g. fat) or nodularity (cirrhosis).

FIGURE 7.12

CT scan of abdomen showing a hepatocellular carcinoma (arrow), confirmed on biopsy. Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

6.

Fibro-scanning

. This can be used in place of biopsy to help diagnose cirrhosis.

7.

In the setting of dyspnoea, consider

hepatopulmonary syndrome

. Platypnoea (dyspnoea that is worse when the patient sits up and is relieved by lying down) and orthodexia (arterial desaturation when upright) are strongly suggestive; a diagnosis of intrapulmonary vascular dilatation may be possible by contrast echocardiography.

8.

Always assess for possible causative factors (see

Table 7.8

).

•

Obtain hepatitis B and C serologies.

•

Screen for antimitochondrial antibody (AMA) if primary biliary cirrhosis is suspected. In suspected chronic hepatitis (e.g. young woman with raised globulins) test for antinuclear antibody (ANA), smooth muscle antibody, and anti-liver and kidney microsomes type 1 (anti-LKM1) antibody. In type I autoimmune chronic hepatitis there is marked hyperglobulinaemia, and ANA and anti-smooth muscle

antibody (ASMA) are present. In type II, ANA is negative, but anti-LKM1 is present in high titre and liver cytosol antigen may be present (this antibody also occurs in low titre in hepatitis C). In the rare overlap syndromes, the only serological abnormality may be AMA, but the histology shows autoimmune hepatitis or the patient is ANA or ASMA (but not AMA) positive and has primary biliary cirrhosis (autoimmune cholangiopathy) on histology.

•

Order iron studies and, in a young patient, caeruloplasmin levels. Alpha

1

- antitrypsin deficiency should be considered; absence of the alpha1 fraction on a protein electrophoresis is a useful clue.

•

Evaluate for evidence of inflammatory bowel disease if there are colonic symptoms. Perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA) occur in up to 80% of patients with ulcerative colitis and are a marker for primary sclerosing cholangitis (60% of cases).

•

Screening for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is recommended for patients with cirrhosis secondary to hepatitis B or C. Screening is now by 6-monthly liver ultrasound.

•

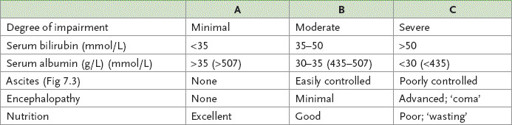

Assess the hepatic functional reserve of patients with known or suspected cirrhosis (

Table 7.12

).

Table 7.12

Child’s classification of patients with cirrhosis in terms of hepatic functional reserve

8.

Liver biopsy

. This is a definitive test and probably should be done if the diagnosis is uncertain, unless there are specific contraindications (e.g. coagulopathy).

HINT

The Child Pugh score can be used as an

aide-memoire

for the complications of CLD viz. jaundice, coagulopathy, poor nutrition, ascites, encephalopathy.

Treatment

Decide whether the patient has acute or acute-on-chronic disease and decide whether the disease is compensated or decompensated. Management includes treating hepatocellular failure (synthetic function) and portal hypertension (plumbing). Cirrhosis is irreversible. However, removing causative factors, such as alcohol, iron overload and drugs, or treating viral infection is of value.

HEPATOCELLULAR FAILURE

Acute hepatic encephalopathy is precipitated by bleeding into the gastrointestinal tract or electrolyte disturbances (alkalosis increases the ammonia crossing the blood–brain barrier, whereas hypokalaemia increases renal ammonia production). Hypokalaemia may be caused by recent diuretic use. Infection (e.g. spontaneous bacterial peritonitis), drugs (e.g. sedatives), a high-protein diet, constipation, deteriorating liver function (e.g. alcoholic binge, hepatocellular carcinoma) and rarely metabolic disturbances (e.g. hypoglycaemia, hypoxia) may also precipitate encephalopathy.

Management

1.

Management consists of removing the precipitating factors. This means removing blood from the gut (e.g. enemas), giving a low-protein diet, treating infection, correcting electrolyte disturbances, avoiding sedatives and attacking the urea-splitting organisms with lactulose (or lactitol; these decrease the pH inhibiting the flora) or antibiotics (e.g. neomycin, metronidazole or rifaximin), or both.

2.

Chronic hepatocellular failure should be managed by treating the cause where possible and manipulating the protein diet as required.

3.

Control encephalopathy and ascites.

4.

Watch for gastrointestinal bleeding and renal failure.

5.

In cases of autoimmune chronic hepatitis, steroids are helpful in patients without viral markers.

PORTAL HYPERTENSION

Clinical features include splenomegaly, the presence of collaterals, ascites and fetor hepaticus. Investigations include endoscopy for oesophageal varices, ascitic tap and abdominal ultrasound with Doppler arterial and venous flow studies.

Management

1.

An attempt should be made to assess the bleeding risk for a patient with varices. High-risk patients (75% risk of haemorrhage over 1 year) are those with Child’s class C cirrhosis, gross ascites and large varices. All patients with large varices should be recommended prophylactic treatment – usually with beta-blockers or, if contraindicated, variceal band ligation.

2.

Bleeding varices should be managed acutely by replacing intravascular volume (transfuse only if the haemoblobin is less than 70 or bleeding is massive) and correcting coagulation abnormalities. Intravenous octreotide or terlipressin (triglycyl lysine vasopressin) or alternatively vasopressin combined with glyceryl trinitrate is first-line therapy but only a temporary measure. Also give antibiotic cover for a maximum of 7 days (e.g. IV ciprofloxacin or oral norfloxacin). Oesophageal variceal banding therapy is effective (and superior to sclerotherapy) in stopping acute bleeding. Balloon tamponade at the gastro-oesophageal junction with the gastric balloon is now rarely required; oesophageal balloon tamponade may worsen the prognosis. To prevent recurrent variceal bleeding, elective endoscopic banding to obliterate varices may be effective. Beta-blockers (e.g. propranolol) can reduce portal pressure and may be useful in patients with good liver function. TIPS is preferable to shunt surgery. Mortality is high for ‘crash’ shunts.

3.

Treatment of ascites consists of gentle diuresis (maximum weight loss of 500 g per day). Begin with bed rest, salt restriction and spironolactone but increase the dose slowly. If the urinary sodium to potassium ratio is >1, a dose of 150 mg/day is usually adequate; if the ratio is less than 1, higher doses are needed. Frusemide is given if necessary. A combination of frusemide 40 mg daily and spironolactone 25 to 100 mg daily may be the most helpful, although there is evidence that spironolactone alone may be as effective. Therapeutic paracentesis is a safe alternative in patients with tense ascites, especially when there is also peripheral oedema. Intravenous salt-poor albumin is given to replace the protein lost in ascitic fluid and 5–10 L can be removed; the procedure can be repeated as necessary. Therapeutic paracentesis is contraindicated in renal failure or severe coagulopathy. These patients are at risk of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Antibiotic treatment (e.g. cefotaxime) is indicated if SBP is suspected (advanced cirrhotic patient presenting with fever, abdominal tenderness or encephalopathy) or the ascitic fluid has a polymorph cell count >250/mm

3

. Usually there is a dramatic clinical response (within 5 days); otherwise repeat the paracentesis. SBP is associated with a poor 6 months survival. Antibiotic prophylaxis is also indicated in an upper GI bleeder with cirrhosis.