Evening's Empire: The Story of My Father's Murder (11 page)

Read Evening's Empire: The Story of My Father's Murder Online

Authors: Zachary Lazar

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #BIO026000

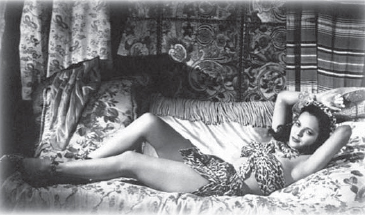

Acquanetta

O

ctober 3, 1971—about a month after Warren had flown to Tachikawa, Japan, to present the board members of CMS with photographs, a fact sheet, and a preliminary grid of Jack Ross’s acreage of “green, rolling hills” at Chino Grande, outside Seligman. He had also brought a promotional letter from Senator Barry Goldwater, in gratitude for which CMS had offered Warren the loan of their spokesman, the actor Cesar Romero, who stood now under a white pavilion set up outside the clubhouse at Verde Lakes, greeting a kind of reception line of thirty or forty prospective buyers who had just arrived in a fleet of vans from Phoenix.

On their way to meet the former movie star and current supporting player on TV’s

Alias Smith and Jones,

the prospective buyers could help themselves to a paper cup of fruit punch laid out on the buffet table covered in a plastic cloth held in place by clothespins. Cesar Romero shook their hands, bowing slightly forward at the waist, courtly, Latin. Many of the people in line remembered him from his days as a romantic lead, dancing with Carmen Miranda or Betty Grable. They remembered him as Hernan Cortez with a silver breastplate and flowing sleeves in

Captain from Castile.

They were flattered to meet him, and his presence, along with the pennants and picnic tables and chairs, made the empty streets of Verde Lakes, some of them nothing more than dirt ruts, some still not even bladed by the bulldozer, look like the early growth of what would someday be a functioning town.

“He’s worth the thousand dollars,” said Harry Gillis of CMS, who had flown over from Japan that week to see Verde Lakes and Chino Meadows and Jack Ross’s Chino Grande, which he would do tomorrow from Ross’s private plane. Gillis was a handsome balding man with sideburns and an easy California smile. He had an enthusiasm for sports cars. He was bright, genial, but when Ed asked him a few token questions about his family, there emerged a murky picture of a wife and son back in Seattle whom he never saw. Money did odd things to people, made them migrate to Japan, but perhaps Gillis’s move hadn’t been for the money but for the distance. Gillis was an Irish name, Ed thought—Catholic, no possibility of divorce.

Cesar Romero made a blank face and bent down low to hear what an older woman was trying to communicate to him, her hand on his biceps, raising her chin, a white sun visor coming down over her forehead and large black-lensed sunglasses covering her eyes. She was a kind of woman Ed recognized: opinionated, not just unwilling but incapable of hearing anything that did not fit into her line of argument. She didn’t realize that Romero knew even less than she did about Verde Lakes or Chino Meadows or the investment potential of real estate in Yavapai County.

“A thousand dollars a day,” Ed said. “I guess basically he gets paid to feel ridiculous for a couple of hours.”

“Acting. Just a different kind of acting,” said Gillis.

“We can go inside the clubhouse and have a real drink if you want.”

“No, I’m all right. I haven’t seen one of these sales promos in a long time. I’m getting kind of a kick out of it.”

Ed looked over toward a couple standing in line. “It’s always geared toward the wife,” he said. “The pitch, I mean. It’s usually the wife who makes all the decisions. Either that, or she can’t stand it when her husband looks like a cheapskate. The salesman hands her a notepad and he says, ‘Write this down. You’ll want to remember these figures.’ It gets her used to following instructions. On the other hand, it makes her feel like she’s important, the one in charge. The longer the husband says nothing, the more she starts to get interested in the whole project. You’d be surprised how much emotion these guys create. Anxiety. Humiliation. Then they say, ‘Isn’t it beautiful out here? Don’t you just love the fresh air?’ I’ve actually seen them sometimes—they’ll bend down and pick up a handful of dirt and talk about how beautiful it is, how there’s nothing like good, clean desert soil. The husband is standing there with this look on his face like his feet hurt. By then, the salesman looks like Tony Bennett compared to him. That’s the way these deals work a lot of the time.”

Gillis sniffed a little laugh and looked down at his shoes. “We do it mostly with brochures,” he said, “brochures and promises.” He looked around with something like a poetic squint. “Does it get very hot here in the summer?”

“It gets pretty hot. Not like Phoenix, but hot. In the hundreds.”

“And what about Chino?”

“Chino’s the same.”

“There’s trees, a water table. It’s not like it’s the sandy wastes.”

“We’ll take a drive over there after lunch. It looks like this. Trees, hills, more lush than maybe you’d expect.”

“You’re talking about Chino Meadow.”

“Chino Meadows. With an

s.

I’ve never seen the other one, Chino Grande, but you’ll see that tomorrow with Ross.”

At a pair of large charcoal grills, a few cooks were flipping hamburgers onto plastic trays. The air smelled like burnt meat, lighter fluid, smoke. Pennants flapped in the breeze—white and green and yellow. There was a long table set up with ketchup, pickle relish, yellow mustard, bags of buns, and, still in their plastic crate, large bottles of Mr Pibb. Cesar Romero, as if dreading the imminence of this lunch, came over to say good-bye. He appeared unrealistically clean and pressed, his collar still bright white, his suit jacket buttoned. With his white hair and mustache, he looked not like the Joker he played on

Batman

but like an anchorman or a game show host. It was surprising, nevertheless, how strongly his fame asserted itself. He wore it like a glass panel through which everyone on the other side appeared amusing, harmless, neutral.

“I must go,” he said. “Many thanks. It was a pleasure to meet you both.”

“Thank you, Cesar,” said Gillis.

“Thank you,” said Ed.

Romero shook their hands. “This is very interesting. This development will be for trailers?”

“Some mobile homes, some houses,” said Ed.

“Well, I wish you nothing but the best,” Romero said, backing away. “We say in Spanish,

!Te la comiste, hoy!

” He looked at the sky, breathing in through his nose. “It means, ‘You ate it!’ ” He smiled. “But really it means, ‘You’ve had a great success.’ Really, a great success today.

!Un triunfo grande!

”

He walked away, and Ed and Gillis didn’t say anything.

“He actually thinks we’re stupid,” Gillis finally commented.

“I guess it would be hard to blame him.”

“He bats for the other side, you know. That’s basically an open secret.”

Ed’s secretary, Sharon, brought them over some plates of food once the prospective buyers had finished helping themselves. There was very little you would want to eat. Sharon herself had found some cottage cheese, but she would never have considered offering that to a man, so Ed and Gillis did their best with the gray hamburgers and the sweet beans in their puddles of sauce.

“Maybe I’ll take you up on that drink after all,” said Gillis.

They headed over toward the clubhouse. The sales team was offering door prizes to a dozen of the prospective buyers. The prizes were S & H Green Stamps, sheets of little stamps you pasted into a book and redeemed for merchandise. The winners of the stamps were also given blue ribbons—the salesmen pinned the ribbons onto their shirts, as if bestowing an honor, smiling at their own guile. The winners had been selected not at random but after the salesmen had had a chance to observe what they were like. The blue ribbons indicated easy marks—“mooks,” in the parlance, “Mickey Nothings,” “Johnny Zeroes.” These were the ones you tried to sell not one but four or five lots, working out a financing plan, tying their heads in knots with complicated discounts and plans for resale with an eighteen-month option.

“I think you can see why we’re interested in getting out of the retail side,” Ed said.

Gillis nodded as he followed Ed into the shade of the clubhouse. He was chewing his burger and looking at his fact sheet for Chino Grande, holding it awkwardly beneath his paper plate. “You think we’re better off just driving to Grande today after we see Meadow?” he said. “That way I could skip the plane ride tomorrow with Ross, maybe catch an earlier flight back to L.A.”

Ed shrugged. “Honestly, I wouldn’t know how to get there. I think they’re still working on the road.”

It came to him as they stepped into the clubhouse: the emptiness of Gillis. The sales meetings, the dinners in hotel rooms, the auditoriums, the airports. It was always better not to think too much about the lives of other men, especially those you didn’t know very well, but he couldn’t stop thinking about Gillis with a Scotch in a plastic cup, flying to California from Japan, then on to Phoenix—his toilet kit, his Robert Ludlum novel—all so that he could report back on this sales program in the desert.

Six thousand acres at two hundred per brings you to a million two plus commissions and fees.

He realized then that Gillis was not crooked but perhaps so bored and apathetic that he was in his own way a kind of risk.

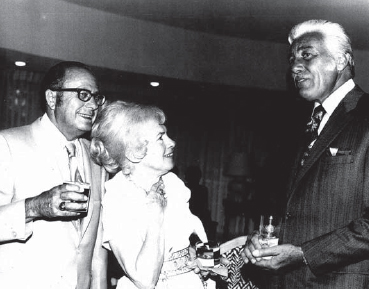

Cesar Romero, with the author’s grandparents, Louis and Belle Lazar

N

ot long after the AHI merger, Ed had come back to the office one afternoon to find one of his former sales managers, James Cornwall, waiting for him in his office. Cornwall’s Rolls-Royce had been sitting in the parking lot, a white Silver Shadow with UK plates, a car he’d bought from Warren not long before this. Cornwall stood up when Ed came in, holding a hand to his stomach to keep his tie in place as he rose from his seat. There was something studied about the gesture, along with the expensive silk tie that picked up a deep navy thread in Cornwall’s sport coat. He was tall, with a blond crest of hair slicked back with brillantine. It occurred to Ed that the more compromised a person became, the more compelled he was to draw attention to himself. Or perhaps it was the opposite: the showiness made you a “character,” so colorful that no one, not even the authorities, took you very seriously. Cornwall was a deputy in something called the Sheriff’s Posse, a fund-raising group whose members were entitled to wear silver stars and ten-gallon hats like the lawmen to whom they wrote their checks.