Evening's Empire: The Story of My Father's Murder (10 page)

Read Evening's Empire: The Story of My Father's Murder Online

Authors: Zachary Lazar

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #BIO026000

Capital Management Systems was called CMS. Consolidated Mortgage Corporation was called CMC. The new umbrella they began to work under was called Consolidated Acceptance Corporation, or CAC, a separate corporation from CMC. It was going to be very hard for people to keep track of what was what or who was who: CAC, CMC, CMS. As it went forward, even the secretaries would sometimes get the different letterheads mixed up.

. . .

Warren stacked some papers on his desk, his forehead still shiny from the heat outside. He had just returned from his long weekend on the beach in Mexico. He wore a tan suit and a pale blue shirt and he sucked on a Dum Dum lollipop because he was trying to cut down on his smoking.

“I get bored on the beach after about ten minutes,” he said. “Nothing to do.” He was in his Robert Mitchum mode, dapper and sarcastic, breezing into the office now to check his mail, then breezing to his other offices, then back to his house and the pool.

Ed sat down in one of his chairs. He could play this game as long as Warren wanted to. He wasn’t going to be the one who mentioned the letter that had just arrived that morning from Barry Goldwater.

“How was the marijuana down there?” he said.

Warren pretended to shiver. “No comment.”

“Well, at least you got out of this inferno for a few days.”

“I may have a lead on some more land. Straight brokerage deal. No financing, no salesmen, nothing.”

“Where?”

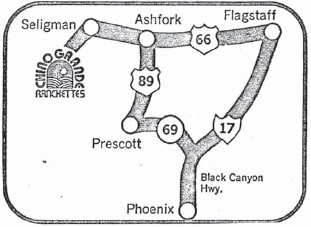

“Near Chino. It would be a good favor for us to do. But let’s worry about Chino first.” He examined his lollipop, glaring at it for not being a cigarette. “This one’s called Chino, too, actually. Chino Something-Else. Chino Grande.”

Ed knew Warren was waiting for him to bring up the Goldwater letter. He knew Warren knew he was thinking this. It was a game they played, a telepathy of withholding, in some ways more important than whatever words they ever actually spoke. When they spoke, it was jokes, banter, cocktail talk, punctuated by a two-minute phone call or a terse memo written almost anonymously.

Got it,

was the only note Warren had appended to the Goldwater letter, for, as they both appreciated, any further comment would only diminish the impact of the signature at the bottom: just the first name,

Barry,

in firm blue ink.

Ed had been in the men’s room that morning when Fred Greene, the collections agent, had come in and walked over to the urinal. Greene was six six and weighed almost three hundred pounds, standing there with both hands on his hips, the man who knocked on doors when a mortgage went unpaid.

“Your salesmen are all worried about their jobs,” he said, scowling down as if pissing were a kind of indigestion. “They’re all trying to make a hundred thousand in sales before their business gets shipped overseas to Japan or Taiwan or wherever the hell it is.”

Ed stared into the mirror as he washed his hands. “They’ll still have jobs,” he said.

Greene flushed the urinal. His shoes were as big as galoshes, white with silver chains. “These guys would sell to a dead man if they could keep their commissions.”

“Yeah, well, that’s why we have Mean Fred Greene.”

Greene moved toward the sink, pumped soap powder all over the basin, then washed his hands under full pressure from the tap. After pounding his hands dry on a thick stack of paper towels, he threw the towels on the floor by the wastebasket. Not in the basket, but on the floor.

Ed nodded, his silence a coded laugh that Greene acknowledged with more silence, not looking but seeing.

Ed thought, if the CMS deal worked and the lot sales happened in Japan instead of here, then he wouldn’t have to think about any of this anymore—not the salesmen, not the commissions, not the stupidity, not the greed. He wouldn’t have to see Fred Greene tossing his garbage on the men’s room floor. He would see numbers, contracts, memos, statements. He would take his seat on the board of AHI and after a reasonable amount of time had elapsed, he would sell his shares and get out of the business.

Mr. Dave Martin

Capital Management Systems Ltd., Inc.

P.O. Box 364

Koza, Okinawa

Dear Dave:

Best wishes on your investment program for the ownership of home-sites in Chino Valley, Arizona.

Much of Arizona’s phenomenal growth has been due to the fact that many service men that were based in Arizona during their training decided to make their home here in their civilian life. These men have contributed a great deal to the vitality and growth of our State. This program should be an additional step along these lines. We wish you continued success.

With best wishes,

Barry Goldwater

Ed put it back in its manila envelope and looked again at the memo he’d written yesterday:

TO:

N. J. Warren

FROM:

Edward Lazar

We will want a letter from Sam Steiger that will read something like the following:

Mr. Dale Holmgren

Mr. Dave Martin

Mr. Dale Hunt

Mr. Harry Gillis

Capital Management Systems Ltd., Inc.

P.O. Box 364

Koza, Okinawa

Dear Mr. So and So:

Best wishes on your investment program for the ownership of home-sites in Chino Valley, Arizona.

Much of Arizona’s phenomenal growth has been due to the fact that many service men that were based in Arizona during their training decided to make their home here in their civilian life. These men have contributed a great deal to the vitality and growth of our state. Your program should be an additional step along these lines. Continued success.

Sincerely,

Sam Steiger

“No one’s heard of Sam Steiger,” Warren had said on the phone yesterday, speaking from his house. “Sam Steiger’s just a congressman from Arizona.”

“He’s helping us out with the Forest Service,” Ed had said.

“So get him, too,” Warren had answered, as if with a shrug.

The memo had been delivered to Warren’s house by messenger boy and then the letter had been dictated to Goldwater’s office by someone over the phone—that was the only way it could have happened in less than twenty-four hours. That also explained some minor differences in a few of the sentences. But he couldn’t imagine Warren patiently reading a letter over the phone, making subtle changes of phrasing. The phrases would have been changed by someone’s secretary, probably Goldwater’s, but how the letter had even made it that far was a mystery.

It was the Wild West—that was the phrase that covered such mysteries. He could have asked Warren how the Goldwater letter had materialized, how it had happened in less than twenty-four hours, but it was the kind of question you knew not to ask after two years in the land business. They had connections to a lot of people. Now they somehow had connections to Barry Goldwater. He wondered if not just Sam Steiger but Barry Goldwater owned land in Chino Valley.

“I need a favor,” Jack Ross had said that afternoon in Mexico, standing at the bar, drinking whiskey because that was what he drank, even by a pool. “That land I told you about, I don’t know what I’m going to be able to do with it.”

Warren nodded. “It’s called Chino Grande?”

“That’s right. They did up a flier already. Chino Grande Ranchettes.”

“Outside Seligman.”

“Far outside. There’s no road.”

“But it’s in Chino Valley.”

“Not really Chino Valley. It’s north of there.”

“We’ll call it Chino Valley. That way we’ll keep it simple.”

Their conversation would have happened on August 14. The Goldwater letter was dated August 19. The first time Warren mentioned the Jack Ross land to Ed Lazar was a month later, in September. There were reasons for doing it this way, reasons for spacing out the favors so that no one could connect them too easily.

CAC, CMC, CMS. Chino Valley, Chino Meadows, Chino Grande. This is how you can become a party to fraud without quite knowing it, without the perpetrator necessarily even planning it that way.

Ed drove home that evening in his new car. He liked it even less than his last car, which had been a Cadillac. Like the Cadillac, the new car, a Lincoln, had been Warren’s idea. It made Ed feel silly—it was ostentatious, it cost more than his house was worth—but there was only so much you could explain to your friends and family about the performative aspects of the land business. At the Lincoln/Mercury dealership in Mesa, Jack Ross had gone over all the details before handing Ed the keys—the Kashmir Walnut Matina paneling, the Cartier timepiece, the small, oval-shaped “opera” windows in the back—all the details that made the Lincoln Continental Mark IV different from last year’s Lincoln Continental Mark III. It had a grille in front, designed to mimic a Rolls-Royce’s, and a rounded, old-timey hump in the rear where the spare tire fit. Ed pulled it into his driveway now and opened the garage door and hid it inside—he never left his company cars in the driveway. He turned his back on the closed garage and faced the sunlight.

It was 103 degrees, the heat a white sheen on the houses and the asphalt cul-de-sac. His son Zachary and Zachary’s friend David Nichols were playing on a plastic slide hooked up to a garden hose in the front yard of David’s house. He left his briefcase in the driveway and started walking toward them, knowing that he would get his suit pants wet when Zachary came running over. Susie and Carol must have been inside Carol’s house in the air-conditioning. He would say hello and then he would go back home and change into his bathing trunks and he and the boys would splash around in the plastic pool in the backyard. That was what he wanted to do. It seemed remarkable, after getting out of that car on the day the Goldwater letter arrived, that this was what he wanted to do.