Essex Land Girls (18 page)

Authors: Dee Gordon

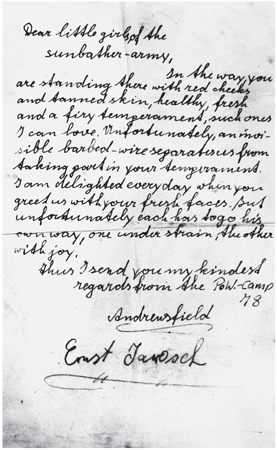

The prisoner-of-war letter picked up by Joyce. (Braintree District Museum Trust)

It is fascinating to hear how dominant memories can be of both the minor and the trivial, often superseding memories of hardship. More fond memories follow in the next chapter.

Not All Work

At the End of the Working Day

Dances featured prominently as a favourite way of spending an evening for just about every member of the WLA, in complete contrast to their hardworking rural day. A fit

Vicky Phillips

cycled 15 miles to dances at RAF Sawbridgeworth, but not as often as she would have liked to, because this feat would follow a hard day’s work.

East Ender

Gladys Pudney

enjoyed dances at Writtle College, and even an ‘occasional ball at the Shire Hall’ in nearby Chelmsford, while the girls billeted in Layer-de-la-Haye saved their clothing coupons to be able to buy fashionable clothes for the dances in the local village hall, dancing the night away with servicemen posted in this rural area.

Although

Jean Watsham

remembers dances at West Mersea, she says there ‘was nothing at East Mersea except whist drives’. Those girls in the vicinity of Great Dunmow (there was a hostel in Oakroyd Avenue, for instance, near Dunmow Park) were invited regularly to dances at the RAF Dunmow base, built on a landed estate of ancient parkland at Easton Lodge.

The dances later in the war, where there were mostly Americans, were the best fun according to

Hilda Gentry

. She and other Land Girls managed to retain a ‘couple of decent things to wear, and borrowed from each other if it was a special date’ but mostly it meant ‘being picked up in a lorry and taken to one of the American USAAF bases – Wethersfield [near Braintree], Dunmow and Stansted’. The ‘yanks’ at Stansted arrived in 1942, ‘gorgeous and glamorous creatures’ turning a quiet village ‘upside down’, according to Ann Bernstein in

Land Army Days

. She spoke of a ‘generous, happy-go-lucky bunch of men’, with cooks who would provide ‘beef sandwiches’ and who attended Saturday night dances at the Stansted Hostel, ‘smuggling in some beer’ against the supervisor’s instructions.

There were also dances, apparently dominated by Canadians, in the Royston area, ‘at an airbase near Nuthampstead [over the border in Hertfordshire]’. A truck would arrive in Mersea a couple of times a week from Stansted to collect

Babs Newman

and other Land Girls for their dances. She recalls the Americans ‘teaching us to jive’, accompanied by ‘lovely bands and loads of food’ not to mention the ‘nylon stockings’. Her mother kept a few brief letters proclaiming: ‘Won’t be home this weekend because there is a dance here at Takeley [near Stansted].’

Colchester barracks was another venue for regular dances with Land Girls from Essex and Suffolk in attendance. And ‘Friday night at 7’ at Woodham Walter had ‘become famous’ for its dances, according to

The Land Girl.

The Americans that

Amy Rogers

met at the Stansted dances were ‘very protective’ and, in fact, ‘they visited the WLA hostel’ where she was staying, and could be relied on to arrive pronto ‘in their jeeps’ if a bomb was dropped nearby.

Margaret Penfold

remembers the Americans she met in Chelmsford as being ‘brash’, while

Ivy Cardy

describes them as ‘generous’. There were plenty of soldiers billeted at Hyland’s Park in Chelmsford, providing ample dancing partners. A couple of the girls featured in

Land Army Days

also refer to the Americans in Essex as generous and ‘happy-go-lucky’ men in ‘smart uniforms’ with happy laughter and ‘decent food’.

Winifred Daines

thought that the American dances ‘were superior’ to those arranged by the British, and that – as far as she was concerned – the ‘hundreds of Americans’ at local airfields (Gosfield near Braintree and Saling at Great Dunmow) ‘treated the Land Army Girls well’. Some were more wary of the ‘yanks’, like

Maude Hansford

and the girls billeted at Thundersley, who declined the offer of a lift ‘from the American Air Force’ to one dance, with ‘only the hostel’s warden’ ending up on the lorry!

Ashingdon church hall was mentioned by

Elsie Haysman

as her local venue for dances with ‘American and British servicemen’ in attendance – and she remembers silk stockings, which obviously made quite an impact in times of rationing and clothing coupons. The local village hall was the venue for dances in South Woodham Ferrers when

Kathleen Firmin

was working there, although she also spent some of her spare time playing badminton, so she must have had plenty of energy left at the end of the working day. Dances were a weekly event for Land Girls and army and air force personnel working in the Loughton or Woodford area: at Abridge or Stapleford Tawney Airfield.

Winifred Daines, née Wretham (right), with jauntily tipped hat. (Braintree District Museum Trust)

The ‘yanks’ did not get as far as Pebmarsh village hall, it seems, because this is where

Mary Page

attended dances, although she was just as happy playing darts in the local, the King’s Head, and didn’t feel she’d missed out socially by not living in a hostel. They did get as far as the village dances at Wix, though, as

Barbara Rix

remembers them, along with ‘sailors from Harwich’. A ‘band led by the local butcher’ used to play at these dances, ‘plus an old lady played the piano but wouldn’t play if the Americans jitter bugged’. Although Barbara’s little village put on a few dances, she was more likely to spend time ‘writing letters and knitting – with rationed wool’, and she was only allowed in the front room of her billet on Sunday evening.

According to

Rene Wilkinson

, the hostel at Stansted was the venue for a dance every Tuesday, with the Americans invited. Four of the girls would be appointed to ‘serve coffee, doughnuts and ice cream to the officers who always looked grey and worn’. But Rene also spent a lot of time in a quieter pursuit – playing cards. Girls from the WLA hostel at Coggeshall favoured the Polish Army dances, with a lorry available to collect them and take them back. Recollections of these dances, in particular, are on file at Braintree District Museum, and it seems that if the girls could not get a late pass they would arrange to stay in Mrs Baker’s house in the village which meant not just sharing a room, but sharing a bed for 1

s

each without breakfast or washing facilities.

The cinema was a popular ‘outing’ for WLA girls in Essex. The Empire in Mersea Road was – as many were – up and running during the Second World War, and

Margaret Penfold

remembers ‘walking in a line down the middle of the lane because there was no lighting. We went, in uniform, to see

Casablanca

.’ However, for East Ender

Ellen Brown

the nearest cinema was in Chelmsford, a bike ride from Galleywood where she was based, ‘and there was nowhere to leave your bike if you went there’ nor were there any late buses.

Some of the more musical girls enjoyed a sing-song.

Betty Cloughton

used to sing in the local pubs, including The Chequers in Wickham Bishops, and also remembers jiving in the local public hall. Similarly,

Eva Parratt

would play the violin to entertain her peers, while

Joyce Willsher

:

… used to play the piano to get the customers in and sing my heart out. There were about eight little pubs in town [Waltham Abbey] – e.g. The Sun, The Welsh Harp and The Cock Hotel – and I played the piano in most of them, all by ear as I never learnt music; but it was better than nothing to cheer people up … I used to get up on the stage in the Cricketers in London Road [Southend] in my uniform and sing ‘Don’t Fence Me In’ to entertain the troops, in return for a free drink.

Singing for soldiers waiting to go to war ‘was quite sad, as we didn’t know if we would see any of them again’. It seems it wasn’t only the troops that Joyce entertained, because at the Fox & Hounds (Waltham Abbey) she also entertained the prisoners of war who ‘showed us pictures of their families’.

Rita Hoy

also reminisced about sing-songs ‘at the village pub’ (Castle Hedingham) and about a recreation hut with a piano, games and occasional dances, and a canteen to buy coffee or dried fruit cake. But

Connie Robinson

stressed the difficulty of getting from her rural billet to Southminster – boasting seven pubs – for a drink on Sunday as there was just one train in the morning and one at night. The social life for the girls working in the St Osyth area near Clacton was focused on the Flag Inn, a hub for the agricultural community according to

Vera Pratt

. Lifts were available from local farmers, sing-songs were enjoyed by all, and the village school put on occasional dances.

Some of the girls in rural areas had little in the way of a social life due to problems either with transport or with a lack of facilities within easy reach. The girls in the hostels definitely had the superior social life, but it wasn’t all dances and sing-songs, as at the end of a tiring day, some just hit their beds or caught up with domestic chores.

Dorothy Jennings

wrote of ‘cleaning my hat and coat with Thawpit’ (no longer in the shops, folks …) and of an evening ‘mending two pairs of stockings’.

Mark Hall at Harlow was apparently a stunning building for the 120 or so Land Girls living there, complete with grand staircase, marble fireplaces, an enormous dining room and mirrors everywhere. There was a room set aside for relaxation, and a piano in the hall, with at least one visit from an ENSA (Entertainments National Service Association) party. Members of the Dagenham Girl Pipers, who worked the land in Essex, were also members of ENSA and it seems that they even took their pipes along ‘to work’ to provide entertainment where needed!

The pleasures inherent in listening to and playing music as a leisure activity were made clear in the

Chelmsford Chronicle

of 10 April 1942 with the following appeal for ‘Pianos for Essex Land Girls’:

The Essex War Agricultural Executive Committee have been asking for pianos to hire or to loan for use in their hostels. One piano has already arrived and there are several other replies to be dealt with. There are about twenty hostels in Essex from wooden huts to requisitioned houses and specially built hostels. A few are given over to labour gangs and men and one to Italian prisoners of war, but most are reserved for Land Girls with new hostels being built. Some of these are in isolated spots and the girls have very little in the way of amusements. Besides pianos, darts and dart boards are badly needed, darts being practically unobtainable now. Several ping pong tables have been lent for the duration but demand is greater than supply. Each hostel is equipped with a radio and the Committee is trying to make hostel life as attractive as possible to keep the girls out of the country pubs. Anything in this line will be gratefully received by the Committee at the Institute of Agriculture, Writtle.

The level of entertainment provided for the US troops, however, was second to none, and a number of Land Girls were lucky enough to see Bob Hope when he visited the Americans at Wethersfield, while others saw Bing Crosby giving a concert at Great Dunmow for the troops nearby. (Note the different mindset of the 1940s which meant that it was rare for white and black American servicemen to mix, even at such events, and Land Girls were actively discouraged from fraternising with black troops.)

These entries from the diaries of

Eva Parratt

give some insight into her social activities:

29.8.1942 | Lovely dance at Co-op Hall [Colchester]. Met a Canadian and an American. |

1.9.1942 | Dance at Abberton. Was quite in demand. |

9.9.1942 | Cycled to Colchester to hear Reverend Shaw’s talk on slums. |

18.5.1943 | Went to dance at the Legion. Got chucked about like a ball by a half-drunk Canadian. |