Essex Land Girls (16 page)

Authors: Dee Gordon

A smaller problem (literally) were the fleas many girls came into contact with. When

Connie Robinson

was working near Maldon, she first noticed the itching during her lunch when seated in a barn. Later the same day, all the girls in her ‘gang’ joined her in the incessant scratching. Told it ‘was only fleas’ (although there were nits to contend with too), the girls were advised ‘not to worry’. What it did mean though was that the ‘first one back [to Mangapp’s, a ‘large-ish’ hostel at Burnham-on-Crouch] could run a bath and get rid of them’ even though they didn’t like to admit their existence. Baths, although not always available, were also deemed necessary for those who had been working in greenhouses with tomatoes (that stained the hands yellow) or with coloured and/or smelly dyes.

Barbara Rix

caught ‘ringworm from the cattle, and had chilblains from milking’, which involved moving from handling the warm milk to the cold outside.

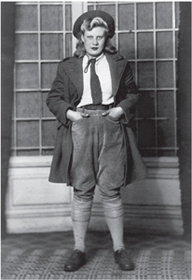

Dorothea Strange (née Nevison) looking glamorous. (Courtesy of Sandra Parker)

Unloading ‘hefty bags of lime’ and ending up with burned arms was something

Audrey Clarke

remembered in a 1989 article by Jenny Brogan in the

Gazette & Citizen

. She was working at a poultry farm in Braintree at the time, and her uncovered arms left her exposed to real peril – as did ‘lifting the very heavy bags’, and the strain this put on her heart ending her employment in 1946.

Dorothy Jennings

also had a number of health issues, reported in her diaries. She wrote often of sore throats, headaches and toothache, and was off work for three weeks at one point with German measles when working around Brentwood.

The sun itself was something a lot of girls were not used to, especially those that had been working in offices before joining the WLA. In the summer, many hours were spent in the heat, and not a lot of the girls favoured wearing a protective hat. The suntan, by the Second World War, was being cultivated as an asset, but sunstroke could be serious, as with one girl

Winifred Daines

remembers when working at Witham: ‘We had to drag her across the railway line and put her under a tree to provide some shade, but she then had to wait there until the lorry picked her up at 5 p.m.’

Gladys Pudney

also remembers one of her fellow Land Girls getting ‘sunburn during harvesting’.

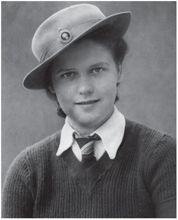

Dorothy Jennings (née Foster) in formal pose. (Courtesy of Marion Dowling)

At the other extreme, one of the jobs that

Vicky Phillips

had was to act as a ‘human scarecrow’ at Harlow, working alone in the snow, when she ‘passed out, and came to in an army hut with tea made with condensed milk’. It seemed that she was suffering from snow blindness, her bird-scaring days at an end.

Some girls, of course, were not used to early mornings or the primitive rural conditions on offer in remoter areas. The

Essex Newsman

of 17 July 1943 pointed out that WLA girls were leaving field work on the ‘marsh farms’ because the farm cottages used as billets ‘were often without gas or electricity’ not to mention the lack of ‘shopping and transport facilities’. It suggests that the WLA ‘girls were more interested in picking fruit’ – and this may well have been true, in some cases at least. However, those employed on apple farms, for instance, would have had to spray the trees several times a year with quite poisonous chemicals.

Then there was the war! Girls working in greenhouses were vulnerable if a doodlebug cut out nearby, the resultant explosion causing shattered windows and flying glass. Land Girls like

Lillian Woodham

could be called upon to help out with fire-watching – ‘looking out for fire bombs, land mines and doodlebugs’. Two anonymous Land Girls in Essex had a letter published in the August 1940 issue of

The Land Girl

pointing out that although ‘the air raids are horrid … we just keep smiling. We are doing all sorts of interesting jobs … and we are now thistle dodging! … It is up to us to be cheery.’

In February 1945, over twenty girls went to the aid of a crashed American fighter plane at Felsted. They had been working at Glandfields Farm and Camsix Farm in the area, and helped local farm workers release the experienced pilot, Lieutenant Hardee, from the cockpit. The aircraft’s engine had failed near Glandfields Farm on the Chelmsford Road, and the aircraft had clipped a tree, cartwheeled and smashed, just yards from where the girls were working. (According to the local parish magazine, he was taken to the US hospital in Braintree but later died of his injuries.)

Mary Marsh

wrote the following account regarding her experience when billeted at Sewardstone Hall, in Epping:

Late one November evening in 1944, a V2 rocket landed just 10 yards off, to the rear of the main farm buildings, it took most of the roof of the farm house off and the dairy which was close by, demolished a large barn where the tractors were parked and taking out all the windows everywhere else, the crater was big enough to put two buses in. A farm worker’s bungalow was close by the edge of the crater, damaged of course but thankfully no serious casualties. The five LA girls got covered with glass and plaster but no one was hurt, in fact three had to be woken up having slept through the explosion! When I looked up to the ceiling, having been awakened by our ‘foster mother’ all I saw was stars and clouds and rafters!

Getting the cows in from the fields early morning: it was not an uncommon sight to see and hear V1s pop-popping in the sky as they passed over, it became rather scary when the motor stopped for one never knew where it would come down.

When

Amy Rogers

was working on a farm near Debden Airport, it became the location for ‘one of my worst experiences of the war’. The airport was bombed, ‘but no one and no animals were hurt’ (this must have been a reference to one of the later attacks, because in fact in August 1940 the airport came under more than one attack from the Luftwaffe, with a number of casualties).

Woodredon Farm, where Diana Thake worked, was near North Weald Airfield, and a 2005 edition of the

Loughton & District Historical Society Newsletter

reported that

‘bombs fell on the farm. We often saw air battles and German planes like little dishes in the sky. It was frightening, but we had had it for so long.’ When the war was over, she remembers ‘the relief … a tremendous feeling. We left the hedging and ditching early and came back for a cup of tea. Sir Fowell [Buxton] thanked us so much for our work in helping to keep the farm alive, and there was extra in our wage packets.’

There was ‘firing all around’ on one occasion when

Betty Shaw

was cycling the 1.5 miles from Danbury to work, and ‘hectic fighting above most nights’ when she worked on a poultry farm at North Hill, Little Baddow, during the Battle of Britain. ‘The night of [her] first air raid was spent under a holly bush with terrified chickens while the fighting went on overhead and spent bullets rattled around on the ground.’ On another occasion, ‘a small bomb landed on the end of the cowshed, and my favourite cow, Nora, was killed, but the men working there were more upset by the fact that it was Monday and they had all been wearing clean overalls’. As for Betty, she ‘cried all day’.

It was the preparations for D-Day that stuck in

Ellen Brown

’s mind. She recalls the ‘whole main road lined with trucks … and troops asleep on Galleywood Common [near Chelmsford]’ because they were obviously ready for ‘a big push’.

As for

Elsie Haysman

, she almost came face to face with the enemy when a low-flying plane ‘machine-gunned the lorry we were in, travelling back from Foulness … the lorry was damaged but the girls escaped … I could see his [the pilot’s] face in his helmet.’

When

Hilda Gentry

saw the terrible state of the flying fortresses returning overhead to the airbase at Nuthampstead, her heart went out to the brave men inside. However, the Blitz was over by the time

Margaret Penfold

joined the WLA, although she remembers ‘a direct hit at Chelmsford’ when she was ‘living in a private billet there’. The main experience of bombing related by

Barbara Rix

was with regard to her visits home to war-torn Leyton in East London. She did hear:

… some bombs roundabout, but nothing very close [to Wix]. But the Home Guard were everywhere, even the farmer was in the Home Guard … I did think I saw a German parachutist coming down one day but it was just a lump of sacking.

She also remembers ‘VJ Day – when someone made a treasure hunt which involved locating bombs!’

The Land Girls billeted in Wigborough Road, Peldon, had a lucky escape when an AA (anti-aircraft) shell fell in the middle of the road in February 1944, outside their hostel. Luckily, no one was hurt, and the only damage recorded was to the gate and some of their bicycles.

Many Land Girls in Essex were able to watch the bombing of London with a heavy heart and not always from a safe distance. One of the girls featured in

Land Army Days

refers to the German bombers flying ‘over our hostel’ (at Stansted) so often that the area ‘became known as Flying Bomb Alley, and we often had to dive under tables and chairs when the alarm went off’. Although ineffectual, even diving into a hedge (like Doris Barker on the ‘Wartime Memories Project’ website) in Valentines Park seemed to be considered a way of escaping a doodlebug overhead. In her case, Doris was lucky that the bomb fell quite a distance away, as she became stuck in the hedge and needed help to get out again.

It wasn’t just the enemy that caused problems.

Mary Page

wrote of how, during her milk round at the little village of Twinstead she ‘could see and hear an American bomber coming down’. She didn’t know what to do and her ‘horse was petrified’. The plane ‘landed in the field’ behind a thatched cottage and the men got out, ‘shaken up but not hurt’. They said they had ‘missed the cottage roof by a quarter inch’ but Mary wanted to know if there were any bombs on board. They said not, because ‘they had left them over Germany’ much to her approval. As for the horse, also shaken up, he took quite a while to settle down after this experience.

A jaunty hat style was adopted by Mary Page (née Nichols). (Braintree District Museum Trust)

While working near Bradwell Bay Aerodrome,

Vicky Phillips

ventured out alone one dark night to meet a friend and came across ‘well over 100 Commandos blacked up and completely silent. They frightened the life out of me, but nothing was said.’ Apparently, there was a squadron leader that she knew at Bradwell:

… who had died just when taking off. He hit the trees and was literally beheaded, apparently because the water had reflected on the runway … [it was not uncommon] for aircraft to land in the water … I saw a plane coming into land with one wing badly damaged [but it] landed safely, and the crew kissed the ground. A band was playing, the crew were all crying … a sad memory which always comes back to me when I hear ‘Beneath the Lights of Home’

[by Deanna Durbin].

The account of the crash of the American Liberator bomber on 12 June 1944, when returning to Nuthampstead Airport, given in

Clavering at War

, includes the reaction of Nancy Caton who was working as a Land Girl under the flight path. She saw the plane coming across around 7 a.m. and the crew jumped out ‘as fast as they could’. They landed safely, with just one broken ankle between them, and Nancy remembers ‘coming across flying boots in the corn’ during the summer harvest.