Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber (59 page)

Read Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber Online

Authors: Geoffrey Block

By the end of 1956 Laurents had completed his fourth libretto draft (out of eight), and much of the eventual version was fixed. The most significant changes in the months prior to and during the rehearsal schedule from mid-June to mid-August 1957 were the addition of two songs, “Something’s

Coming” and “Gee, Officer Krupke,” and considerable revamping of the opening Prologue. Also in 1957 more dance numbers would be added to the “Dance at the Gym” (only the “Mambo” was indicated for this section at the end of 1956); Tony’s and Maria’s “One Hand, One Heart” on the tenement balcony had still not been replaced by “Tonight.”

30

The Prologue and first scene, which had already undergone a number of changes in the first four librettos (all in 1956), required considerable revision before it achieved its revolutionary final version in the summer months of 1957. Although Bernstein exaggerates the ease with which he and his collaborators worked out the solution to the complex problems posed by this opening, the libretto and musical score drafts support his recollection in 1985 that the Prologue was originally intended to be sung: “It didn’t take us long to find out that it wouldn’t work. That was when Jerry [Robbins] took over and converted all that stuff into this remarkable thing now known as ‘the prologue to

West Side Story

,’ all dancing and movement.”

31

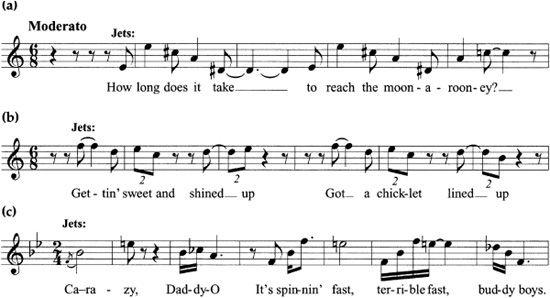

The three sung themes of “Up to the Moon” (

Example 13.3

) found their way into the instrumental Prologue and the instrumental portions of the “Jet Song” as we know it. A fourth theme (and much of the text) from “Up to the Moon” was salvaged in the eventual Broadway version of the “Jet Song,” when the Jets sing “Oh, when the Jets fall in at the cornball dance, / We’ll be the sweetest dressin’ gang in pants!”

32

In Laurents’s fourth libretto (Winter 1956) the opening scene had shifted from a clubhouse to an alleyway, but it is not until the similar fifth and sixth librettos (April 14 and May 1, 1957) that the first scene—none of the eight librettos indicate a Prologue distinct from a first scene—begins to resemble the final version shown in the online website.

33

Example 13.3.

Vocal passages from “Up to the Moon” reused in Prologue and “Jet Song”

(a) “How long does it take?”

(b) “Gettin’ sweet and shined up”

(c) “Carazy, Daddy-O”

Sondheim recalled in the 1985 Dramatists Guild symposium that

West Side Story

“certainly changed less from the first preview in Washington to the opening in New York than any other show I’ve ever done, with the exception of

Sweeney Todd

, which also had almost no changes.”

34

In

Sondheim & Co

. he comments further on the extent of these alterations: “Our total changes out of town consisted of rewriting the release for the ‘Jet Song,’ adding a few notes to ‘One Hand,’ Jerry

potchkied

with the second-act ballet, and there were a few cuts in the book.”

35

Again, the evidence from the music manuscripts and libretto drafts substantiates Sondheim’s recollection on all these points. Bernstein’s early piano-vocal score reveals the rejected release for the “Jet Song” and two versions of “One,” the original one-note-per-measure version and the familiar three-notes-per-measure version.

36

And in what is perhaps the most significant

potch

of the dream ballet sequence, “Somewhere” was originally intended to be danced rather than sung, at least until its conclusion when Tony and Maria reprise the final measures.

Sondheim also remembered Robbins’s preoccupation during the tryouts with a number that would be eventually rejected:

Jerry had a strong feeling that there was a sag in the middle of the first act [scene 6], so we wrote a number for the three young kids—Anybodys, Arab, and Baby John. It was called “Kids Ain’t” and was a terrific trio that we all loved, but Arthur gave a most eloquent speech about how he loved it also but that we shouldn’t use it, because it would be a crowd-pleaser and throw the weight over to typical musical comedy which we agreed we didn’t want to do. So it never went in.

37

During the July rehearsals Robbins & Co. had taken steps to remedy the lack of a comic musical number caused by the removal of “Kids Ain’t.” Although there had been a comic exchange between Officer Krupke and the Jets in act II, scene 2, in the four 1956 libretto drafts, no song had yet appeared in this space. Only in the final libretto draft did a recycled “Where Does It Get You in the End?” from

Candide

materialize as “Gee, Officer Krupke.” Sondheim recalled that Robbins staged this number “in three hours by the clock, three days before we went to Washington.”

38

At the time, Sondheim thought that “Officer Krupke” would be better placed in act I, since its presence detracted from the serious developments in the drama. After viewing the 1961 film in which “Krupke” and “Cool” were reversed “and weren’t nearly as effective,” Sondheim came to accept Robbins’s directorial decision and to acknowledge that “Krupke” “works wonderfully” in act II on the basis of its “theatrical truth” rather than its “literal truth.”

39

Since its comic intent was meant to provide dramatic contrast and relief from the mostly tragic theme based on tritones and “Somewhere” motives (to be discussed), the absence of the latter and the softening of the former in “Krupke” is understandable and dramatically plausible and welcome.

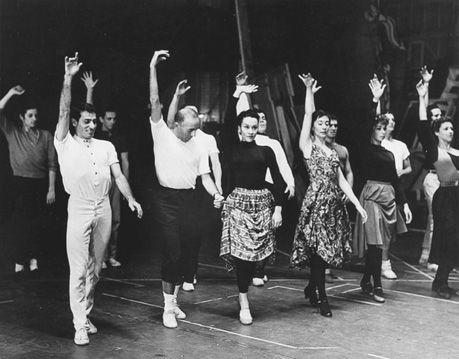

Jerome Robbins (second from left) rehearsing

West Side Story

(1957). Museum of the City of New York. Theater Collection.

After “Krupke,” one final song, not indicated even as late as the final libretto draft of July 19, was added during rehearsals.

40

This song, newly composed to conclude act I, scene 2, after Tony promises Riff that he will attend the Settlement dance, is, of course, “Something’s Coming.” Bernstein describes the circumstances and motivation for this song:

“Something’s Coming” was born right out of a big long speech that Arthur wrote for Tony. It said how every morning he would wake up and reach out for something, around the corner or down the beach. It was very late and we were in rehearsal when Steve and I realized that we needed a strong song for Tony earlier since he had none until “Maria,” which was a love song. We had to have more delineation of him as a character. We were looking through this particular speech, and “Something’s Coming” just seemed to leap off the page. In the course of the day we had written that song.

41

At Robbins’s suggestion, Laurents added the meeting between Tony and Riff in front of the drugstore, and in the course of the Washington tryouts the song “Something’s Coming” replaced much of the dialogue.

42

Sondheim’s recollection that the song ended with its eventual title is partially borne out by the Winter 1956 libretto, which concludes with the following exchange:

TONY

: Now it’s right outside that door, around the corner: maybe being stamped in a letter, maybe whistling down the river, maybe—

RIFF

: What is?

TONY

: (

Shrugs

). I don’t know. But it’s coming and it’s the greatest…. Could be. Why not?

43

In contrast to “Gee, Officer Krupke,” the purpose of which was to provide a respite from the surrounding tragedy, the motive behind “Something’s Coming” was to introduce a main character and to link this character to the ensuing drama.

44

This is accomplished musically by allowing Tony to resolve a dissonant and dramatically symbolic interval (the interval of hate, a tritone) at the beginning and conclusion of his song.

In order to understand the Romantic qualities inherent in

West Side Story

it may be helpful to recall that the nineteenth century, an age obsessed by the theme of idealized youthful passionate love that realizes its apotheosis only with premature death, was irresistibly drawn to Shakespeare’s

Romeo and Juliet

.

45

Not only did this play—in various degrees of fidelity to Shakespeare—occupy the European stage throughout most of the nineteenth century, numerous musical settings also made their debut. Just as revisions of Shakespeare’s play from the late-seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries frequently included a happy ending, most of the musical adaptations strayed conspicuously from the

original. Gounod’s still-popular

Roméo et Juliette

(1867), for example, introduces a major female role (Stephano) that has no Shakespearean counterpart.

46

Although these operatic, orchestral, and balletic versions, unlike

West Side Story

, retain the names of the major characters and basic plot machinations, they more often than not distort Shakespeare’s tragic intention with the insertion of either a happy ending (like many play performances) or an ending that enables the principals to sing (or dance) an impassioned love duet before their demise. Consider Prokofiev’s ballet (1935–36), one of the most popular of the twentieth century and most likely an inspiration for Robbins. After its premiere, Soviet Shakespearean scholars influenced censors to prohibit Prokofiev and his collaborators from allowing Romeo an extra minute in order to take advantage of his pyrrhic opportunity to witness Juliet alive. Prokofiev defended his original scenario: “The reasons that led us to such a barbarism were purely choreographic. Living people can dance, but the dead cannot dance lying down.”

47

Modern-day nonmusical versions of Shakespeare’s play are similarly prone to alterations that can distort the meaning and tone of the Bard (or eliminate substantial portions of text), presumably for the sake of broader public palatability. The well-known 1968 film of

Romeo and Juliet

by director Franco Zeffirelli, probably the most popular film adaptation of Shakespeare ever made, serves as an instructive paradigm for the triumph of accessibility over authenticity introduced in

chapter 1

(even though the eponymous principals die). One may acknowledge the need to make a Shakespeare movie cinematic and argue on behalf of the many artistic merits of Zeffirelli’s considerable textual excisions, but the conclusion is nonetheless inescapable that Zeffirelli has succeeded more brilliantly in bringing himself rather than Shakespeare to a mass audience.

48

Although it contains extensive transformational liberties, the tragic dramatic vision of

West Side Story

arguably corresponds more closely to Shakespeare than Zeffirelli’s version or nineteenth-century musical adaptations that wear the garb of the Montagues and the Capulets. Robbins spoke of Laurents’s achievement in following the “story as outlined in the Shakespeare play without the audience or critics realizing it,” but most theatergoers familiar with the characters in Shakespeare’s tale of “fair Verona” can easily recognize their West Side reincarnations.

49

While preserving the central theme of youthful passionate love’s Pyrrhic victory over passionate youthful hate and many of the central plot elements from the Shakespearean source, adapted to suit New York gang culture of the 1950s, the collaborators took four major transformational liberties:

1. Increased motivation for the conflict between the gangs

2. Decreased importance of adults

3. Substitution of free will for fate in the demise of Tony

4. Decision to keep Maria alive

Most obviously, the warring gangs, the Jets and Sharks, parallel the warring families, the Montagues and Capulets.

50

Like Romeo at the outset of Shakespeare’s play, Tony, a Jet, has disassociated himself from the violent members of his clan. His friend, Riff, shares the fate and much of the mercurial character of Romeo’s friend, Mercutio. Maria appears as an older and therefore more credible Juliet for modern audiences. Bernardo’s death has a more direct emotional impact because he is Maria’s brother rather than a literal counterpart to Juliet’s cousin Tybalt. By 1957, New York City teenagers were less likely to share intimacies with an aging nurse. Consequently, Anita, a woman only a few years older than Maria, serves as a more credible counterpart to Shakespeare’s elderly crone, a confidante to Maria, and of course an agile dancing partner for her lover, Bernardo. Chino, Maria’s unexciting but eventually excitable fiancé and Bernardo’s choice for his sister, corresponds closely to Juliet’s parentally selected suitor, the County Paris.