Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber (32 page)

Read Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber Online

Authors: Geoffrey Block

Weill’s remaining borrowing falls between these extremes. “The Greatest Show on Earth,” the rousing march that opens the Circus Dream, borrows significantly from the melody, rhythm, and dissonant harmonic underpinning of the refrain of

Kingdom

’s “Auftrittslied des General.” When drafting his melody in its new context and new meter, Weill began by retaining the rhythmic

gestus

(to be discussed shortly) and symmetrical phrasing of its predecessor, altering only the pitch. By the time Weill completed his transformation, he had added a new syncopation at the ends of phrases and reinforced the sense of disarray by concluding his phrase one measure earlier than expected. In real (and especially military) life, marches contain symmetrical four-measure phrases; in Liza’s confused dream message a seven-measure phrase makes more sense.

Partisans of Brecht may be disconcerted to hear the choral refrain “In der Jugend gold’nem Schimmer” from

Happy End

(1929) set to Nash’s words in the opening verses of “The Trouble with Women.” At the time Weill recast Brecht, he had abandoned the possibility of a staged revival of this show, although he had tried in 1932 to interest his publisher in “a kind of

Songspiel

with short spoken scenes.”

38

Perhaps his sense that all was lost with

Happy End

prompted Weill to recycle no less than three numbers from this German show in his Parisian collaboration with Jacques Déval,

Marie Galante

(1934). One of these reincarnations is once again “In der Jugend gold’nem Schimmer,” this time

altered from triple to duple meter in the refrain of “Les filles de Bordeaux.” Despite some modest melodic changes at the opening and closing and the metrical change from the German and American waltzes to the French fox trot, the two—or three—Weills are here much closer to one.

39

The process by which

A Kingdom for a Cow, Happy End

, and

Marie Galante

would reemerge in

Lady in the Dark

and

One Touch of Venus

suggests a deeper than generally acknowledged connection between the aesthetic and working methods of the European and the American Weills. The connecting link is embodied in the concept of

gestus

, a term that eludes precise identification. According to Kim Kowalke, “the crucial aspect of

gestus

was the translation of dramatic emotion and individual characterization into a typical, reproducible physical realization.”

40

In any event, the principle of a gestic music based on rhythm is demonstrable in the aesthetic framework and the compositional process of Weill’s music in America as well as in Europe.

In his 1929 essay on this subject, “Concerning the Gestic Character of Music,” Weill, after explaining that “the

gestus

is expressed in a rhythmic fixing of the text,” makes a case for the primacy of rhythm.

41

Once a composer has located the “proper”

gestus

, “even the melody is stamped by the

gestus

of the action that is to be represented.” Weill acknowledges the possibility of more than one rhythmic interpretation of a text (and, one might add, the possibility of more than one text for a given

gestus

). He also argues that “the rhythmic restriction imposed by the text is no more severe a fetter for the operatic composer than, for example, the formal schemes of the fugue, sonata, or rondo were for the classic master” and that “within the framework of such rhythmically predetermined music, all methods of melodic elaboration and of harmonic and rhythmic differentiation are possible, if only the musical spans of accent conform to the gestic proceeding.”

Weill concludes his discussion of gestic music by citing an example from Brecht’s version of the “Alabama-Song,” in which “a basic

gestus

has been defined in the most primitive form.”

42

While Brecht assigns pitches to his

gestus

—which may explain why he tried to assume the credit for composing Weill’s music—Weill considers Brecht’s attempt “nothing more than an inventory of the speech-rhythm and cannot be used as music.”

43

Weill explains that he retains “the same basic

gestus

” but that he “composed” this

gestus

“with the much freer means of the musician.” Weill’s tune “extends much farther afield melodically, and even has a totally different rhythmic foundation as a result of the pattern of the accompaniment—but the gestic character has been preserved, although it occurs in a completely different outward form.” Several compositional drafts and self-borrowings reveal that in America as well as in Germany, Weill, like Loesser to follow, continued to establish a rhythmic

gestus

before he worked out his songs melodically.

Kowalke suggests that eighteenth-century Baroque

opera seria

served as the aesthetic model for Brecht and Weill’s music drama of alienation widely known as epic opera.

44

Kowalke goes on to describe more specific stylistic similarities, including the relationship between the Baroque doctrine of affections and Weill’s interchangeable song types based on a related gestus.

45

An especially applicable example can be found in the genesis of “My Ship” from

Lady in the Dark

. Both the opening of the second sketch draft and the final version feature a rising diminished seventh, F -A-C-E

-A-C-E (a resemblance noted by bruce d. mcclung).

(a resemblance noted by bruce d. mcclung).

46

It is also clear that Weill had established a

gestus

, if not the melodic working out, by the time he drafted this second draft of five eventual versions.

Just as “Surabaya Johnny” (

Happy End

) constitutes a trope of the “Moritat” (“The Ballad of Mack the Knife”) from

Die Dreigroschenoper

, the borrowed songs in

Lady

and

Venus

may be considered tropes from Weill’s European output. Weill’s practice of salvaging material from failed shows closely parallels the practice of other Broadway as well as European operatic composers as far back as Handel in the Baroque era.

47

What makes such salvaging possible for Weill is a shared

gestus

that might, like the Baroque affections, serve several dramatic situations with equal conviction. Weill would continue to develop this particular brand of transformation within his American works.

Lady

and

Venus

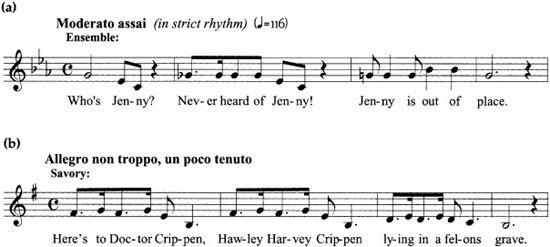

exhibit an especially notable example as shown in

Example 7.1

. Even the theater reviewer, Lewis Nichols, remarked after a single hearing in his opening night review of

Venus

that at the conclusion of act I, Savory “sings the sad story of ‘Dr. Crippen’ in a mood and a tune not unlike that of Mr. Weill’s celebrated ‘Saga of Jenny.’”

48

Example 7.1.

“The Saga of Jenny” and “Dr. Crippen”

(a) “The Saga of Jenny” (

Lady in the Dark

)

Lady in the Dark(b) “Dr. Crippen” (

One Touch of Venus

)

and

One Touch of Venus as

Integrated Musicals

Despite his careful selection of librettists and lyricists and his devotion to theatrical integrity, Weill’s Broadway offerings for the most part share the posthumous fate of such popular contemporaries as Kern, Porter, and Rodgers and Hart who are similarly remembered more for their hit songs in most of their shows.

49

Even in the case of

The Threepenny Opera

, an extraordinarily popular musical in its Off-Broadway reincarnation, “The Ballad of Mack the Knife,” remains by far its most remembered feature.

It is additionally ironic that the ideal of Weill’s most successful musical deliberately disregards the principle of the so-called integrated model popularized by Rodgers and Hammerstein, a principle that would hold center stage (with some exceptions) at least until the mid-1960s. In Europe, the apparent interchangeability of arias (providing the proper affects were preserved) in

opera seria

gave way to the increasingly integrated, albeit occasionally heterogeneous, operas of Mozart, Verdi, Wagner, Strauss, and Berg. Many Broadway shows before Rodgers and Hammerstein (and some thereafter), like their Baroque opera counterparts, emphasized great individual songs, stars, and stagecraft more than broader dramatic themes and treated their books and music as autonomous rather than integrated elements.

After

Oklahoma!

and

Carousel

the aesthetic goals of Broadway shifted. Two years after the disastrous

Firebrand of Florence

in 1945 (43 performances), Weill too composed an integrated dramatic work,

Street Scene

(148 performances), that would eventually achieve a commercial success roughly commensurate with its critical acclaim. The dream that Weill shared on his notes to the cast album of this Broadway opera, a “dream of a special brand of musical theatre which would completely integrate drama and music, spoken word, song and movement,” was also the dream of his chief Broadway rival in the 1940s, Rodgers, who was composing

Oklahoma!, Carousel, Allegro

, and

South Pacific

during these years.

50

In his notes to

Street Scene

, Weill acknowledges that he and his earlier collaborator Brecht “deliberately stopped the action during the songs which were written to illustrate the ‘philosophy,’ the inner meaning of the play.”

51

It was not until

Street Scene

, however, that Weill achieved “a real blending of drama and music, in which the singing continues naturally where the speaking stops and the spoken word as well as the dramatic action are embedded in overall musical structure.”

52

Three years before he completed his long and productive theater career, Weill appeared to repudiate the aesthetic he had worked out with Brecht and achieved his integrated American opera.

Thus Weill, by now a wayward branch from the German stem, did not begin his serious attempt to integrate drama and music until after he ceased collaborating with Brecht. On the other hand, Rodgers, in America, as early as Brecht and Weill’s

Threepenny Opera

, was already somewhat paradoxically striving to compose integrated musicals in a marketplace somewhat indifferent to this aesthetic.

53

Weill’s contemporary and posthumous success with

Threepenny Opera

, both its German production in the late 1920s and its Broadway adaptation by Blitzstein in the middle and late 1950s, rests in part in the alienation between and separation of music and story. Even those who remain impervious to the quality and charm of Weill’s many other works acknowledge the artistic merits of

Threepenny Opera

and usually grant it masterpiece status.

Shortly before the debut of

Lady in the Dark

Weill informed William King in the

New York Sun

that in contrast to Schoenberg, who “has said he is writing for a time fifty years after his death,” Weill wrote “for today” and did not “give a damn about writing for posterity.”

54

Between the extremes of his two posthumous success stories,

Threepenny Opera

and, to a lesser degree,

Street Scene

, lie Weill’s two greatest and—if posterity be damned—most meaningful hits. Both

Lady

and

Venus

exhibit integrative as well as non-integrative traits. On one level,

Lady in the Dark

might be considered the least integrated of any book show by any Broadway composer, since the play portions and the musical portions are unprecedentedly segregated. In this respect

Lady

shares much in common with film adaptations of musicals that remove the “nonrealistic” portions of their Broadway source.

55