Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber (31 page)

Read Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber Online

Authors: Geoffrey Block

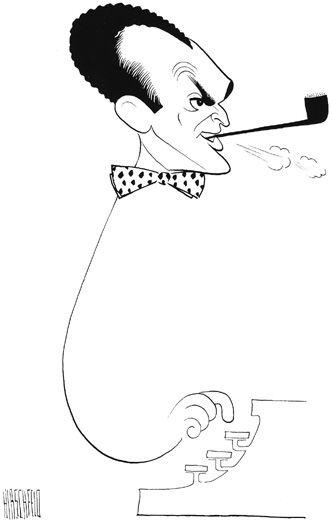

Moss Hart. © AL HIRSCHFELD. Reproduced by arrangement with Hirschfeld’s exclusive representative, the MARGO FEIDEN GALLERIES LTD., NEW YORK.

WWW.ALHIRSCHFELD.COM

Throughout his career Weill rarely failed to surround himself with strong artistic figures. In Germany he collaborated with Brecht and Georg Kaiser. For the American musical stage he worked with a series of distinguished partners as the following list attests: Paul Green (

Johnny Johnson

); Maxwell

Anderson (

Knickerbocker Holiday

and

Lost in the Stars

); Elmer Rice and Langston Hughes (

Street Scene

); and Alan Jay Lerner (

Love Life

). Similarly, the productions of

Lady in the Dark

and

One Touch of Venus

evolved under dynamic leadership, and his principal collaborators, Hart and Gershwin (

Lady

), Nash and Perelman (

Venus

), all possessed strong artistic personalities and identities. The

One Touch of Venus

team could boast an especially impressively deep talent roster. The previous year alone Crawford produced the immensely popular revival of

Porgy and Bess

, Elia Kazan directed his first memorable production, Thornton Wilder’s

The Skin of Our Teeth

, and Agnes de Mille had choreographed Copland’s ballet classic

Rodeo

. Only six months before

Venus

came to life in 1943 de Mille had gained enormous Broadway distinction as the choreographer of

Oklahoma!

21

Even in this venerable company the composer could still play a major role in the creative process of a musical, although he would not occupy the center stage enjoyed by Mozart and Da Ponte, Verdi and Boito, and Wagner. Theater critics appreciated the imagination of the

Lady in the Dark

and

One Touch of Venus

teams, but music critics who focused on Weill felt betrayed by his collaboration with the enemy, men and women of the theater who helped Weill to sell out. Critics Virgil Thomson and Samuel Barlow, respectively, accused Weill of banality and phoniness and wrote that the transplanted European had lost his sophistication and his satirical punch in his efforts to please the lower class inhabitants of Broadway.

22

Considering the experience and prestige of his collaborators, especially Hart and Gershwin, it should come as no surprise that Weill would be asked to defer to the judgment of these collaborators during the writing of

Lady in the Dark

.

23

As a result, one complete dream in

Lady

(first described as the “Day Dream” and later as the “Hollywood Dream”) was rejected before its completion, allegedly to help trim escalating costs. To add pizzazz (and perhaps to avoid racial stereotypes), the “Minstrel Dream” metamorphosed into the “Circus Dream.” “The Saga of Jenny” was a response to Hart’s and producer Sam H. Harris’s assessment that Gertrude Lawrence’s final number was not funny enough, and the patter number which preceded it, “Tschaikowsky,” was added as a vehicle to feature the talented new star Danny Kaye.

Crawford credits de Mille with many of the small cuts in the

One Touch of Venus

ballets, summarizes the problem of the original ending, and explains how Weill’s collaborators achieved a satisfactory solution:

The bacchanal of the nymphs, satyrs, nyads and dryads who carry Venus off was very effective, but it left the audience hanging. It seemed very unsatisfactory for Venus to disappear into the clouds, leaving the poor barber all alone: the ending needed ooomph, something

upbeat. It was Agnes who thought of having Venus come back as an “ordinary” human girl, dressed in a cute little dress and hat—a sort of reincarnation.

24

This new ending necessitated the shortening of Weill’s Bacchanale ballet, which de Mille (as remembered by Crawford) considered “the best thing he’d done since

Threepenny Opera

” and Weill himself treasured as “the finest piece of orchestral music he had ever written.”

25

But since Weill “wanted a success” and was “predominantly a theatre man,” he acquiesced to de Mille’s suggestion.

It is likely that the musical starting point for both

Lady

and

Venus

were songs that Weill had written for earlier contexts. Both of these songs,

Lady

’s “My Ship” and

Venus

’s “Westwind,” would become pivotal to their respective musical stories. Since “My Ship” was originally the only song Hart had in mind when he drafted his play

I Am Listening

, it is not surprising that this was the first song Weill wrote for the show.

26

In the midst of his sketches for

Lady

, including a draft for “My Ship,” Weill sketched a tune that with some modifications would eventually become “Westwind” (

Example 7.2a

, p. 148). In the early stages Weill used its melody solely for the “Venus Entrance” music (and he would continue to label this tune as such throughout his orchestral score). Long after the entire show had taken shape, the music of the future “Westwind” was still reserved for Venus.

27

At a relatively late stage Weill decided to show Savory’s total captivation with Venus musically by adopting her tune as his own. After their first meeting his identity is now fully submerged in the woman he idealizes.

28

The extant manuscript sources and material of

Lady in the Dark

provide an unusually rich glimpse into the compositional process of a musical: Hart’s complete original play

I Am Listening

, two revised scenes for this play, and two typescript outlines for two dreams not included in this play; Gershwin’s lyrics drafts, including those for the discarded “Zodiac” song; and two hundred pages of Weill’s sketches and drafts. Also extant are twenty letters between Weill and Gershwin exchanged between September 1940 and February 1944 (“with random annotations” by Gershwin in 1967) that occasionally reveal important information and attitudes about the compositional process.

29

Gershwin had traveled from Los Angeles to New York in early May 1940 to work with Hart and Weill, and the letters from Weill began one or two weeks after Gershwin’s return in August. The two Weill letters in September are especially valuable because they precede the opening night (the following January 23). On September 2 Weill sets the context for his following suggestions with a budget report: the show was $25,000 above its projected $100,000. Hart and

Hassard Short “read the play to the boys in the office,” who were “crazy about the show” but thought “that the bar scene and the Hollywood dream had nothing to do with the play.”

30

Hart asked Weill to cut the Hollywood Dream, and the composer agreed to do this if Hart agreed to delete the bar scene as well.

Did this compromise breach Weill’s artistic sensibilities? Apparently Weill did not think so. He explains his positive reaction to the excision of the Hollywood Dream:

I began to see certain advantages. It is obvious that this change would be very good for the play itself because it would mean that we go from the flashback scene directly into the last scene of the play. The decision which Liza makes in the last scene would be an immediate result of the successful analysis. The balance between music and book would be very good in the second act because we would make the flashback scene a completely musical scene.

31

Although Weill regretted losing “an entire musical scene and some very good material,” he saw artistic benefits as well as financial ones, and agreed to these changes.

After more discussion on the relationship between the Hollywood Dream and the Hollywood sequence, both eventually discarded, Weill turned to the “Circus Dream.” Here Weill was less acquiescent to Short’s suggestions. Although he understood that “Gertie” (Gertrude Lawrence) might remain dissatisfied until he provided “a really funny song” for her, Weill was not yet ready to abandon his “Zodiac” song and defended its place in the show to Gershwin. Although Weill acknowledged that the “Zodiac” song “is not the kind of broad entertainment which Hassard has in mind,” he concluded that “it is a very original, high class song of the kind which you and I should have in a show and for which we will get a lot of credit.” Because Weill also recognized “the necessity to give Gertie a good, solid, entertaining, humorous song in the Circus dream,” he offered to make the “Zodiac” song “musically lighter, more on the line of a patter, and to think about another song for Gertie.”

On September 14 Weill again commented on the evolving Circus Dream:

So Moss and Hassard suggested that we give the Zodiak song back to Randy and I thought this might be good news for you because that’s what we always wanted. Here is Moss’s idea: the Zodiak song would become Randy’s defense speech, just the way you had originally conceived it, but we should try to work Gertie into it…. When they have won over everybody to their cause, Liza should go into a triumphant song…. That would give Liza her show-stopping (??) song near the end of the dream and at a moment where she is triumphant and which allows her to be as gay or sarcastic as you want.

32

Lady in the Dark

. “Circus Dream.” Gertrude Lawrence sitting on the left, Danny Kaye on the horse at right (1941). Photograph: Vandamm Studio. Museum of the City of New York. Theater Collection. Gift of the Burns Mantle Estate.

From Ira Gershwin’s 1967 annotations that accompany his manuscripts as well his published comments in

Lyrics on Several Occasions

, we learn that the “Circus Dream” was originally planned as a “Minstrel Dream” and “an environment of burnt cork and sanded floor” was transformed “to putty nose and tanbark.”

33

Gershwin divides the “Zodiac” into two parts, “No Matter under What Star You’re Born” and “Song of the Zodiac,” “both of which were discarded to make way for “The Saga of Jenny.”

34

He also notes that he and Weill “hadn’t as yet introduced ‘Tschaikovsky.’”

35

Weill’s musical manuscripts add credence to the letters and Gershwin’s annotations and reveal that when most of the Circus Dream nearly reached its final form, “The Saga of Jenny” was just taking shape. It is ironic that Gertrude Lawrence’s final number and Danny Kaye’s patter show stopper that directly preceded it were the only musical portions originally written for this dream. All the other musical material—with the exception of some recitative—was borrowed from earlier shows. Even the lyrics to “Tschaikovsky” were borrowed

unchanged from a 1924 poem published in “the then pre-pictorial, humorous weekly

Life

” that Ira published under the pseudonym Arthur Francis.

36

Weill’s 1935 London box office debacle,

A Kingdom for a Cow

, served as an important musical link between the German Weill and the American Weill. In his

Handbook

, Drew lists thirteen major instances of Weill’s recycling ideas from this most recent European venture into every American stage work from

Johnny Johnson

and

Knickerbocker Holiday

(two borrowings each) to

The Firebrand of Florence

.

37

The two

Kingdom for a Cow

borrowings in

Lady in the Dark

both occur in the Circus Dream: the opening circus march, “The Greatest Show on Earth,” and “The Best Years of His Life.” The single borrowing in

One Touch of Venus

occurs more obliquely in “Very, Very, Very.”

Of the

Kingdom for a Cow

borrowings in

Lady

and

Venus

“The Best Years of His Life” comes closest to quotation. In fact, Kendall Nesbitt’s melody in

Lady

is identical to the choral melody in the first act finale of

Kingdom

, and the rhythmic alterations are insubstantial. Weill takes significant transformational liberties, however, in adapting “Very, Very, Very” from

Kingdom

to

Venus

(where it is sung by Savory’s assistant, Molly). On this occasion Weill uses two recognizable but highly disguised melodic fragments of “Madame Odette’s Waltz” from the second act finale of

Kingdom

.