Empires of the Sea - the Final Battle for the Mediterranean 1521-1580 (35 page)

Read Empires of the Sea - the Final Battle for the Mediterranean 1521-1580 Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #Military History, #Retail, #European History, #Eurasian History, #Maritime History

The fighting on the

Sultana

and the

Real

continued for over an hour. A second rush up the deck was again repulsed, but there was a gradual weakening of Ottoman firepower. Don Juan himself fought from the prow with his two-handed sword and received a dagger thrust in the leg. On the poop of his adjacent galley, the eighty-year-old Venier stood bareheaded and fired off crossbow bolts at turbaned figures as fast as his man could reload.

Bazán’s reinforcements were beginning to swing the battle, and the heavyweight galleasses came blasting back into the fray. Pertev Pasha’s ship had its rudder shot away; Pertev jumped ship into a rowing boat manned by a renegade and slipped off, the oarsman calling out in Italian, “Don’t shoot. We’re also Christians!” Pertev cursed Ali’s recklessness as he went. Ships were now closing in on the

Sultana,

snuffing out the supply of men able to reinforce Ali Pasha’s vessel. The pasha’s sons made a desperate attempt to help their father, but were repulsed. Colonna and Romegas captured one galley, then turned to consider the next target.

“What shall we go for next?” asked Colonna. “Take another galley or help the

Real

?” Romegas seized the tiller himself and turned the ship toward the

Sultana

’s right flank. Venier was closing in from the other side, sweeping the deck with fire. “My galley, with cannon, arquebuses, and arrows, didn’t let any Turk make it from the poop to the prow of the pasha’s ship,” he wrote. A third wave of men swept up the

Sultana

’s deck; a last-ditch stand was taking place at the poop deck behind makeshift barricades. Ali Pasha was still furiously dispatching arrows from his bow as the last defenses were blown away. Men were throwing themselves into the sea to avoid the hail of fire.

There are a dozen different accounts of Ali’s last moments, according different degrees of heroism to the pasha. Most probably the admiral, an easy target in his bright robes, was felled by an arquebus shot; a Spanish soldier hacked off his head and raised it aloft on a spear. There were shouts of “Victory!” as the league’s flag was run up to the masthead. Don Juan jumped onto the deck of the

Sultana,

but realizing the fight was over, retired to his own ship. Resistance on the

Sultana

collapsed. Ali’s head was taken to Don Juan, who according to some accounts was gravely offended that his adversary had been so ungallantly decapitated, and ordered the object to be thrown into the sea. The Spanish soldiers mopped up.

Ottoman resistance in the center began to collapse. Ali’s sons were captured on the flagship of Mehmet Bey; others surrendered or tried to flee. According to Caetani, the decks of both the

Real

and the

Sultana

had been reduced to a shambles: “On the

Real

there were an infinite number of dead.” On the

Sultana,

pitching on the slow sea with its crew decimated to the last man, “an enormous quantity of large turbans, which seemed to be as numerous as the enemy had been, rolling on the deck with the heads inside them.”

BUT FOR THE OTTOMANS

the battle was not yet lost. While both fleets were fully engaged at the center, there was still a possibility of snatching victory. Gian’Andrea Doria and Uluch Ali had been playing a game of cat and mouse on the seaward wing, still maneuvering for position an hour after the centers collided.

Doria was a figure of controversy and suspicion in the Christian fleet. His reluctance for this battle, his concern for his own galleys, and his innate caution became grounds for growing concern as Don Juan gazed up at the struggle unfolding to the south. It appeared from the central battle group that Doria was moving too far out to sea, as if trying not to engage. Don Juan dispatched a frigate to summon him back.

More likely Doria had understood from the start the gravity of his position and was working furiously to avoid being caught out. Uluch Ali had more ships; the possibility of outflanking the Christians was considerable. If the Ottomans could outdistance him on the outer wing, they could decimate their enemy from behind. Uluch Ali slid his squadron farther and farther south, pulling Doria with him and enlarging the space between the Christian center and its right wing. A gap opened up, a thousand yards wide. Some of the Venetian ships, fearing treachery by Doria, turned back, fragmenting his line. Uluch Ali, who “could make his galley do what a rider could do with a well-trained horse,” was working with conscious intent. A shrill blast on the whistle and a section of his squadron spun about and headed for the gap, now outflanking Doria on the inside. The Genoese admiral had been out-played. Before he could react, the Ottomans were bearing down on the flank of the Christian center.

IT WAS A BRILLIANT MANEUVER

and a sudden reversal of fortune. Uluch had engineered the kind of broken mêlée the Ottomans wanted to fight. With the wind now behind him, Uluch and his corsairs caught a batch of scattered ships at a serious disadvantage. Ahead of him were the Venetian galleys from Doria’s wing, isolated and in disarray, then the small group of Sicilian galleys, and three vessels flying the familiar white cross on a red ground—Uluch’s most hated enemy, the Maltese galleys of the Knights of Saint John. These detachments were hopelessly outnumbered and already exhausted from the fight. It was now three, four, five to one. Uluch “delivered an immense carnage on these ships.” Seven Algerian ships fell on the Maltese galleys, raking them with a hail of bullets and arrows. The heavily armored but hopelessly outnumbered knights went down fighting. The Spanish knight, Geronimo Ramirez, riddled with arrows like some Saint Sebastian, kept boarders at bay until he fell dead on the deck; the flotilla commander, Prior Pietro Giustiniani, wounded by five arrows and taken alive, was the last man standing on a vessel otherwise devoid of life. The Sicilian galleys pulled up to help but were immediately engulfed in a storm of fire; the

Florence

was overrun by a galley and six corsair galliots; every soldier and Christian slave was killed. On the

San Giovanni

a row of chained corpses slumped at the oars; the soldiers were all dead and the captain felled by two musket balls. There were no survivors on the Genoese flagship of David Imperiale or on five of the Venetian galleys. The flagship of Savoy would be found later drifting on the water, totally silent, not a man left to tell the tale.

There were extraordinary moments of thoughtless bravery on these stricken Christian ships. The young prince of Palma boarded a galley single-handed, fought the crew back to the mainmast, and lived to tell the tale. On the stricken

San Giovanni,

the Spanish sergeant Martin Muñoz, lying below with fever, heard the enemy clattering up the deck overhead, and leaped from his bed determined to die. Sword in hand, he hurled himself at the assailants, killed four, and drove them back before collapsing on a rowing bench, studded with arrows and with one leg gone, calling out to his fellows “Each of you do as much.” On the

Doncella,

Federico Venusta had his hand mutilated by the explosion of his own grenade. He demanded a galley slave cut it off. When the man refused, he performed the operation himself and then went to the cook’s quarters, ordered them to tie the carcass of a chicken over the bleeding stump, and returned to battle, shouting at his right hand to avenge his left. A man hit in the eye by an arrow plucked it out, eyeball and all, tied a cloth around his head, and fought on. Men grappling their assailants on deck dragged them overboard to drown together in the bloody sea. The

Christ over the World,

surrounded and overrun, blew itself up, taking the encircling galleys with it.

Despite this resistance, Uluch Ali was tearing a hole in the Christian line, collecting prizes as he went. He took in tow the Maltese flagship, strewn with dead bodies, as a trophy for the sultan. A little sooner and he might well have tipped the battle, but with the Ottoman center now collapsing, his chance was ebbing away. Doria regrouped to attack Uluch’s ships from one side; Colonna, Venier, and Don Juan brought their galleys around to confront him from the other. The wily corsair certainly had no intention of dying in a lost cause; he cut the towrope on the Maltese flagship, leaving the wounded Giustiniani to tell the tale but prudently taking its standard as a trophy. Steering to the north with fourteen galleys, he slipped off.

The Christian ships turned to mopping up and looting. The battlefield was a devastated scene of total catastrophe. For eight miles guttering vessels burned on the water; others floated like ghost ships, their crews all dead. The surviving Muslims fought courageously to the last. There were moments of grotesque comedy. Some ships refused to surrender; running out of missiles, they picked up lemons and oranges and hurled them at their attackers. The Christians, wrote Diedo, “out of disdain and ridicule, retaliated by throwing them back again. This form of conflict seems to have occurred in many places towards the end of the fight, and was a matter for considerable laughter.” Elsewhere men still thrashed and fought in the water, clung to spars, or casually drowned. Chroniclers struggled to convey the scale of the carnage. “The greater fury of the battle lasted for four hours and was so bloody and horrendous that the sea and the fire seemed as one, many Turkish galleys burning down to the water, and the surface of the sea, red with blood, was covered with Moorish coats, turbans, quivers, arrows, bows, shields, oars, boxes, cases, and other spoils of war, and above all many human bodies, Christian as well as Turkish, some dead, some wounded, some torn apart, and some not yet resigned to their fate struggling in their death agony, their strength ebbing away with the blood flowing from their wounds in such quantity that the sea was entirely coloured by it, but despite all this misery our men were not moved to pity for the enemy…. Although they begged for mercy they received instead arquebus shots and pike thrusts.” There was looting on a grand scale. Men put out rowing boats to fish the dead out of the water and rob them; “the soldiers, sailors and convicts pillaged joyously until nightfall. There was great booty because of the abundance of gold and silver and rich ornaments that were in the Turkish galleys, especially those of the pashas.” Aurelio Scetti took two Moorish prisoners in the hope of securing his subsequent release from the galleys; he would live to be disappointed.

It was a scene of staggering devastation, like a biblical painting of the world’s end. The scale of the carnage left even the exhausted victors shaken and appalled by the work of their hands. They had witnessed killing on an industrial scale. In four hours 40,000 men were dead, nearly 100 ships destroyed, 137 Muslim ships captured by the Holy League. Of the dead, 25,000 were Ottoman; only 3,500 were taken alive. Another 12,000 Christian slaves were liberated. The defining collision in the White Sea gave the people of the early modern world a glimpse of Armageddon to come. Not until Loos in 1916 would this rate of slaughter be surpassed. “What has happened was so strange and took on so many different aspects,” wrote Girolamo Diedo, “it’s as if men were extracted from their own bodies and transported to another world.”

The day drew to its mournful close; the bloody water, heaving thickly with the matted debris of the battle, reddened in the sunset. Burning hulks flared in the dark, smoking and ruined. The wind got up. The Christian ships could barely sail away, according to Aurelio Scetti, “because of the countless corpses floating on the sea.” The survivors left with pitiful shouts from the water still ringing in their ears. “Even though many Christians were not dead, nobody would help them.” As the winners sought secure anchorages on the Greek shore, a storm churned the surface of the sea, scattering the debris, as if the ocean were wiping the battlefield away with a great hand.

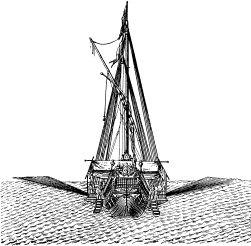

Galley from the stern

THE OTTOMAN CHRONICLER PECHEVI

wrote his own obituary for the battle. “I saw the wretched place where the battle took place myself…. There has never been such a disastrous war in an Islamic land, nor in all the seas of the world since Noah created ships. One hundred eighty vessels fell into enemy hands, along with cannon, rifles, other war resources and materials, galley slaves, and Islamic warriors. All other losses were proportional. There had been one hundred twenty men in even the smallest ships. With this, the total reckoning of men lost was twenty thousand.” And Pechevi was undercounting.

It was Cervantes, hit in the chest by two arquebus shots and permanently maimed in the left hand, who summed up the Christian mood. “The greatest event witnessed by ages past, present and to come,” he wrote.

CHAPTER

22

Other Oceans

1572–1580

A

T ELEVEN A.M.

on October 19 a single galley came rowing into the Venetian lagoon. A ripple of alarm spread among those standing on the water’s edge of the piazzetta of Saint Mark. The vessel appeared to be manned by Turks, yet it came confidently forward. Nearer, the swelling crowd could discern Ottoman banners trailing from its stern; then the bow guns fired a bursting victory salute. News of Lepanto swept through the city. No one had risked more, played for higher stakes, or experienced such extremes of emotion as the Venetians. They had seen Ottoman warships in their lagoon, watched the ransacking of their colonies, lost Cyprus, and endured the terrible fate of Bragadin. Venice exploded with pent-up emotion. There were bells and bonfires and church services. Strangers hugged in the street. The shopkeepers hung notices on their doors—

CLOSED FOR THE DEATH OF THE TURK

—and shut for a week. The authorities flung open the gates of the debtors’ jail and permitted the unseasonal wearing of carnival masks. People danced in the squares by torchlight to the squeal of fifes. Elaborate floats depicting Venice triumphant, accompanied by lines of prisoners in clanking chains, wound through Saint Mark’s square. Even the pickpockets were said to take a holiday. All the shops on the Rialto were decorated with Turkish rugs, flags, and scimitars, and from the seat of a gondola you could gaze up at the bridge where two lifelike turbaned heads stared at each other, looking as if they had been freshly severed from the living bodies. The Ottoman merchants barricaded themselves in their warehouse and waited for the city to calm down. Two months later, in an unaccustomed fit of religious zeal, the Venetians remembered the butcher who had taken his knife to Bragadin, and expelled all the Jews from their territories.

Each of the main protagonists reacted to the news in his own way. According to legend, the pope had already been apprised of the outcome by divine means. At the moment Ali Pasha fell to the deck, the pope was said to have opened his window, straining to catch a sound. Then turned to his companion and said, “God be with you; this is no time for business, but for giving thanks to God, for at this moment our fleet is victorious.” None had worked harder for this outcome. When word reached him by more conventional means, the old man threw himself to his knees, thanked God, and wept—then deplored the exorbitant waste of gunpowder in firing off celebratory shots. For Pius, it was the justification of his life. “Now, Lord,” he murmured, “you can take your servant, for my eyes have seen your salvation.” Philip was at church when the news reached him in Madrid. His reaction was as phlegmatic as Suleiman’s after Djerba: “He didn’t show any excitement, change his expression or show any trace of feeling; his expression was the same as it had been before, and it remained like that until they finished singing vespers.” Then he soberly ordered a Te Deum.

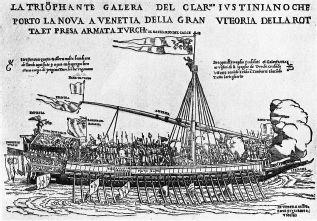

Carrying the news to Venice

LEPANTO WAS EUROPE’S TRAFALGAR,

a signal event that gripped the whole Christian continent. They celebrated it as far away as Protestant London and Lutheran Sweden. Don Juan was instantly the hero of the age, the subject of countless poems, plays, and news sheets. The papacy declared October 7 henceforward to be dedicated to Our Lady of the Rosary. James VI of Scotland was moved to compose eleven hundred lines of Latin doggerel. The Turkish wars became the fit subject for English dramatists—Othello returns from fighting “the general enemy Ottoman” on Cyprus. In Italy, the great painters of the age set to on monumental canvases. Titian has Philip holding his newborn son up to winged victory while a bound captive kneels at his feet, his turban rolling on the floor, and Turkish galleys explode in the distance. Tintoretto portrays Sebastiano Venier, gruff and whiskery in black armor, gripping his staff of office before a similar scene. Vasari, Vicentino, and Veronese produce huge battle scenes of tangled fury, full of smoke, flame, and drowning men, all lit by shafts of light from the Christian heaven. And everywhere, from Spain to the Adriatic, church services, processions of victors and captive Turks, weeping crowds, and the dedication of Ottoman battle trophies. Ali Pasha’s great green banner hung in the palace in Madrid, another in the church at Pisa; in the red-tiled churches of the Dalmatian coast they displayed figureheads and Ottoman stern lanterns and lit candles in memory of the part their galleys played on the left wing.

In the wake of all this euphoria there were small acts of chivalry. Don Juan was said to have been personally upset by Ali Pasha’s death; he recognized in the kapudan pasha a worthy opponent. It is an ironic note that these two most humane commanders, bound by a shared code of honor, had contrived such great slaughter. In May 1573, Don Juan received a letter from Selim’s niece—the sister of Ali’s two sons—to beg for their release. One had died in captivity; the other Don Juan returned, along with the gifts she had sent and a touching reply. “You may be assured,” he wrote, “that, if in any other battle he or any other of those belonging to you should become my prisoner, I will with equal cheerfulness as now give them their liberty, and do whatever may be agreeable to you.” This prompted a response from the sultan in person, still, as ever, “Conqueror of Provinces, Extinguisher of Armies, terrible over lands and seas,” to Don Juan, “captain of unique virtue [courage]…. Your virtue, most generous Juan, has been destined to be the sole cause, after a very long time, of greater harm than the sovereign and ever-felicitous House of Osman has previously received from Christians. Rather than offence, this gives me the opportunity to send you gifts.”

Others were harder-hearted. The Venetians understood that naval supremacy rested less in ships than in men. To the pope’s horror, they sent Venier urgent orders to kill all the skilled Ottoman mariners in his power “secretly, in the manner that seems to you most discreet,” and requested that Spain do the same. With such measures they hoped and believed that the maritime power of the Turk had been decisively broken: “It can now be said with reason that their power in naval matters is significantly diminished.”

In time the Venetians discovered that the tough-minded Ottomans were not shattered by this shattering defeat. The tone was set by Mehmet, Ali’s seventeen-year-old son, two days after the battle. In captivity, he met a Christian boy who was crying. It was the son of Bernardino de Cardenas, mortally wounded at the prow of the

Real.

“Why is he crying?” asked Mehmet. When he was told the reason, he replied, “Is that all? I have lost my father, and also my fortune, country, and liberty, yet I shed no tears.”

Selim was in Edirne when news of the disaster reached him. According to the chronicler Selaniki, he was initially so deeply affected that he did not sleep or eat for three days. Prayers were recited in the mosques and there was fear verging on panic in the streets of Istanbul that, with its fleet destroyed, the city could be attacked by sea. It was a moment of crisis for the sultanate, but its response, under the assured guidance of Sokollu, was prompt. Selim hurried back to Istanbul; his presence, as he rode through the streets with the vizier at his side, seems to have stabilized the situation.

The Ottomans came to use a euphemism for this heavy defeat: the battle of the dispersed fleet. Uluch Ali’s initial report had tried to soften the blow by suggesting that the navy had been scattered rather than annihilated. “The enemy’s loss has been no less than yours,” he wrote to the sultan. As the full scale of the catastrophe sank in, it was received with acceptance, as Charles had taken the shipwreck at Algiers. “A battle may be won or lost,” Selim declared. “It was destined to happen this way according to God’s will.” Sokollu wrote to Pertev Pasha, one of the few leaders to escape with his life (though not with his position), in a similar vein. “The will of God makes itself manifest in this way, as it has appeared in the mirror of destiny…. We trust that-all-powerful God will visit all kinds of humiliation on the enemies of the religion.” It was a setback, not a catastrophe. The Turks even tried to find positives in God’s scourge, quoting a sura of the Koran, “But it may happen that you hate a thing which is good for you.” Yet within the sultan’s domain there could be no clear analysis of the underlying causes. All blame was heaped on the dead Ali Pasha, the admiral who “had not commanded a single rowing boat in his life.” The true reasons for the defeat—the attempt to overmanage the campaign from Istanbul, the struggle for power between the court factions under a weak sultan, the motives for appointing Ali Pasha—these remained hidden. Sokollu himself was suspiciously implicated in these dealings but the subsequent crisis only served to demonstrate his ability and strengthen his grip on power. He moved swiftly and efficiently to manage the situation; orders and requests for information were fired off to the governors of Greek provinces; Uluch Ali was appointed de facto kapudan pasha—all other potential candidates were dead.

By the time Uluch Ali sailed back into Istanbul, he had managed to scrape together eighty-two galleys along the way to make some sort of show, and he flew the standard of the Maltese knights as a battle trophy. This display was pleasing enough to Selim for him not only to spare Uluch’s life but also to confirm the corsair as kapudan pasha—admiral of the imperial navy. And as if to signal a great triumph, the sultan also conferred an honorific name on his commander. Henceforth Uluch was to be known as Kilich (sword) Ali. The knight’s banner was hung in the Aya Sofya mosque as a token of victory. And the Ottoman administration, now under the undisputed control of Sokollu, swung into furious action. Over the winter of 1571–1572, the enlarged imperial dockyards completely rebuilt the fleet in an effort worthy of Hayrettin. When Kilich expressed concern that it might be impossible to fit the ships out properly, Sokollu gave a sweeping reply. “Pasha, the wealth and power of this empire will supply you, if needful, with anchors of silver, cordage of silk, and sails of satin; whatever you want for your ships you have only to come and ask for it.” In the spring of 1572, Kilich sailed out at the head of 134 ships; they had even produced eight galleasses of their own, though they never got the hang of managing them. So rapid was this reconstruction that Sokollu could taunt the Venetian ambassador about their relative losses at Cyprus and Lepanto: “In wrestling Cyprus from you we have cut off an arm. In defeating our fleet you have shaved our beard. An arm once cut off will not grow again, but a shorn beard grows back all the better for the razor.”

And almost immediately the Holy League started to falter. It had recognized the importance of consolidating its victory but proved unable to do so. There was bickering over booty. Then Pius died the following spring. He was spared the gradual collapse of his Christian enterprise. During the campaigning season of 1572, Philip kept his fleet at Messina and Don Juan cooling his heels, preferring a strike in North Africa to further war in the east. Colonna and the Venetians dispatched a substantial fleet anyway to confront the Ottomans off the west coast of Greece, but Kilich was too wily to be caught and did what Ali Pasha should have done: kept his ships in a secure anchorage and let his opponents waste their strength. The following year Don Juan did at least sail to the Maghreb and take back Tunis, but by this time Venice could no longer sustain the fight; in March 1573 they had signed a separate peace with Selim, ceding territory and cash to the sultan on highly unfavorable terms. Philip received the news with “a slight ironical twist of his lips.” Then he smiled to himself. He was blamelessly rid of the expense of the league and the troublesome Venetians; it was their ambassador who was forcibly ejected from the room by the furious Pope Gregory XIII. In 1574 even Don Juan’s triumph at Tunis turned to dust. Kilich Ali sailed to the Maghreb with a larger fleet than either side had mustered at Lepanto and took the city back. He returned to Istanbul with guns firing and captives on the deck; it was like the old days again. The Ottomans were as strong in North Africa as ever; Selim’s mastery of the White Sea seemed to have been fully restored.

NOW THAT THE EXPLOSIVE FEELINGS

that Lepanto released in Europe have been largely forgotten—the pope returned the Ottoman flags to Istanbul in 1965—some modern historians have tended to play down the significance of the battle. What seemed at the time to be Europe’s iconic sea battle that would determine the contest for the center of the world is no longer viewed as a pivotal event like the Battle of Actium fought in the same waters fifteen hundred years earlier to decide control of the Roman Empire, nor that of Salamis, which shattered the Persian advance into Greece. In modern times Lepanto has been labeled “the victory that led nowhere,” on the Christian side a fluke, on the Ottoman side an aberration soon mended. Like the battlefield itself, the Battle of Lepanto appears to have been swallowed by time and the devouring sea.