Empires of the Sea - the Final Battle for the Mediterranean 1521-1580 (33 page)

Read Empires of the Sea - the Final Battle for the Mediterranean 1521-1580 Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #Military History, #Retail, #European History, #Eurasian History, #Maritime History

There are many different versions of what was said, but the party of prudence seems to have been represented by Pertev Pasha, “a man pessimistic by nature,” who pointed out that some of the Ottoman ships were short of men, and almost certainly by Uluch Ali. The weather-beaten corsair, badly scarred on the hand from a mutiny of his galley slaves, was by far the most experienced seaman in the room. He was fifty-two years old and had learned his trade at the side of Turgut. He was intensely feared by the Christians for his courage and cruelty; the previous year he had inflicted a rare humiliation on the galleys of the Maltese knights, and like all the corsairs who had mastered the art of survival, he weighed the odds carefully. It is highly unlikely that Uluch voted for battle. Their argument was clear: “The shortage of men is a reality. From this point of view, it’s best to remain in Lepanto harbor and fight only if the unbelievers come to us.” Others, such as Hasan Pasha, spoke for battle—the Christians were divided among themselves and were numerically inferior.

Ali Pasha’s final verdict was delivered in tones of high bravado. “What does it matter if in every ship there are five or ten men rowers short?” he roundly declared. “If God on high wants it, no harm can come to us.” But behind this display of disregard, there were the orders from Istanbul. According to the chronicler Pechevi, Ali went on, “‘I continually receive threatening orders from Istanbul, I fear for my position and my life.’ Having said this, the other commanders could not oppose him. In the end the decision was taken to go out and meet the enemy.” They went and readied their ships.

Uluch Ali

Toward the end of the day on October 6 the weather shifted. It was a flawless evening. “God showed us a sky and a sea as not to be seen in the finest day of spring,” the Christians recalled. By two the following morning, Sunday, October 7, their fleet was working its way toward the Gulf of Patras. In Lepanto harbor the rattle of anchor chains; one by one the Ottoman ships started to row out through the mouth of the gulf, leaving the protective security of their shore-based guns.

CHAPTER

20

“Let’s Fight”

Dawn to noon, October 7, 1571

Dawn. The wind from the east. A fine autumn day.

T

HE CHRISTIAN FLEET WAS IN THE LEE

of a small group of islands, the Curzolaris, that guard the Gulf of Patras and the straits to Lepanto from the north. Don Juan put scouts ashore to climb the hills and spy the sea ahead at first light. Simultaneously, lookouts from the lead ship’s crow’s nest sighted sails on the eastern horizon. First two, then four, then six. In a short time they could descry a huge fleet “like a forest,” scrolling up over the sea’s rim. As yet it was impossible to determine the number. Don Juan hoisted the battle signals; a green flag was run up and a gun fired. Cheering rang across the fleet as the ships rowed one by one between the small islands and debouched into the gulf.

Ali Pasha was fifteen miles away as the dawn broke and the enemy ships were spotted threading through the islands. He had the wind and the sun at his back; the crews were moving easily. At first he could see so few ships that it seemed to confirm Kara Hodja’s report about the inferior size of the Holy League’s fleet. They appeared to be heading west. Ali immediately assumed that they were trying to escape to open sea. He altered the fleet’s course, tilting southwest to stop the outnumbered enemy from slipping away. There was a feeling of anticipation in the galleys as they surged forward to the timekeeper’s drum. “We felt great joy and delight,” one of the Ottoman sailors later recalled, “because you were certainly going to succumb to our force.”

And yet there were twinges of unease among the men; a large flock of crows, black with ill omen, had tumbled and croaked across the sky as the fleet left Lepanto, and Ali knew that his boats were not confidently manned. Not all the men were happy at the prospect of a sea battle; in places, the number had been made up by compulsion from the area around Lepanto. As each half hour passed, the distant fleet seemed to grow. Far from escaping, they were fanning out. His first impression had been inaccurate; there were more ships than he had thought. Kara Hodja’s count had been wrong. He cursed, and adjusted his course again.

Ali’s initial shift of the tiller had sparked a parallel reaction in the Christian fleet—that the enemy was getting away—then a matching correction at the realization of the true size and intent of the enemy fleet. As the hours passed and the two armadas spread across the water, the full extent of the unfolding collision became apparent. Along a four-mile-wide front, two enormous battle fleets were drawing together in a closed arena of sea. The scale of the thing dwarfed all preconceptions. There were some 140,000 men, soldiers, oarsmen, and crew, in some 600 ships—something in excess of 70 percent of all the oared galleys in the Mediterranean. Unease turned to doubt. There were men on each side secretly appalled by what they saw.

Pertev Pasha, general of the Ottoman troops, tried to persuade Ali to feign a retreat into the narrowing funnel of the gulf, under the shelter of Lepanto’s guns. It was a course of action the admiral’s orders and his sense of honor could not permit; he replied that he would never allow the sultan’s ships even to appear to be taking flight.

There was equal concern in the Christian camp; it was becoming increasingly clear with every successive sighting from the crows’ nests that the Ottomans had more ships. Even Venier, the grizzled old Venetian, suddenly fell quiet. Don Juan felt compelled to hold yet one more conference on the

Real.

He asked Romegas for his opinion; the knight was unequivocal. Gesturing at the huge Christian fleet around the

Real,

he said: “Sir, I say that if the emperor your father had once seen such a fleet as this, he wouldn’t have stopped until he was emperor of Constantinople—and he would have done it without difficulty.”

“You mean we must fight, then, Monsieur Romegas?” Don Juan checked again.

“Yes, sir.”

“Very well, let’s fight!”

There was still an attempted rearguard action by those who remembered Philip’s cautious instructions, but it was now too late. Don Juan’s mind was set. “Gentlemen,” he said, turning to the men assembled in his sea cabin, “this is not the time to discuss, but to fight.”

BOTH FLEETS BEGAN

to fan out into line of battle. Don Juan’s plans had been laid in early September and carefully practiced. They drew on the advice in one of Don Garcia’s letters: to divide the fleet into three squadrons. The center, commanded by Don Juan in the

Real

and closely supported by Venier and Colonna, consisted of sixty-two galleys. On the left wing, the Venetian Agostino Barbarigo with fifty-seven galleys, on the right, Doria with fifty-three. Backing up this battle fleet was a fourth squadron, the reserve, lead by the experienced Spanish seaman Álvaro Bazán, with thirty galleys; his brief was to hurry to the aid of any part of the line that crumbled.

It had been Don Juan’s policy to mix up the contingents to limit the possibility of defection by any one national group and to bind them together; the experience of Preveza lay behind this plan. Nevertheless, the mix had been weighted in various places to fulfill different roles. Forty-one of the fifty-seven galleys on the left wing were lighter, more maneuverable Venetian galleys, whose function was to operate hard up against the shore, following advice from Don Garcia that “if this happens in enemy country, it should take place as close to land as possible, to make it easy for their soldiers to flee from their galleys.” The heavier Spanish galleys occupied the center and the right, where the fight might be more bludgeoning.

The wind was blowing briskly against the Christian ships as they struggled to get themselves into line; Doria’s galleys on the right had to travel farthest to take up their positions. It was a difficult exercise, conducted in slow motion. “One could never get the lighter galleys properly lined up,” Venier recalled, “and it caused me a lot of problems.” It took three hours for the Christians to sort themselves out.

Ali Pasha’s task was made easier by the following wind but his arrangement was broadly similar. The admiral took the center of the battle fleet in his flagship, the

Sultana,

diametrically opposite the

Real;

his right wing was commanded by the bey of Alexandria, Shuluch Mehmet, and his left by Uluch Ali, opposite Doria. As the fleets wheeled and turned, it slowly became clear to the Genoese admiral that he was badly outnumbered. Uluch Ali had sixty-seven galleys and twenty-seven smaller galliots, drawn up in a double line. Doria had just fifty-three. The discrepancy had the potential for serious trouble.

Where Don Juan was trying to hold a straight line, the Ottomans favored the crescent. It had both a symbolic function as the crescent moon of Islam and a tactical one. Both sides had a clear understanding of the realities of galley warfare. All the offensive capabilities of the galley lay in its bows; the three or five forward-facing guns were effective only within a narrow arc of fire, and the bows were the only place where fighting men could gather in any number. The conventional tactics were to sweep the opponent’s deck with cannon fire, arquebus shot, and arrows, then to ram it with the beaked boarding bridge and pour on board. Galley hulls are fragile shells, horribly vulnerable to impact or shot. To be caught sideways or from behind by another galley was to be left literally dead in the water. Ali’s crescent was designed to outflank and encircle the less numerous enemy, then to break up his ranks in a mêlée where the more maneuverable Muslim vessels might catch the ships sideways and pick them off.

FOR BOTH SIDES THE INTEGRITY

of the line abreast was crucial. However, for Don Juan, whose galleys were weightier and more ponderous, the principle of mutual support was a matter of life and death. Each galley needed to be a hundred paces apart—sufficiently distant to prevent a clash of oars but close enough to prevent an enemy from inserting himself into the ranks. For the same reason, it was critical that they remained in line. Too far ahead, a galley could be isolated and picked off; lagging too far back, the enemy could again insert himself into the line and cause havoc. Once holes were picked in the fabric of the battle formation, it became a dangerous game of chance, but to maintain this matrix of order across a four-mile front required extraordinary skill. Seen from the perspective of a bird circling lazily in the higher air, the effects were quite clear. The Christian fleet continually expanded and contracted in and out like an accordion while its line abreast rippled back and forward in sinuous curves as the ships kept trying to adjust their relative positions outward from the

Real

at the center.

Ali Pasha had the same problem. The outer horns of his crescent threatened to get too far ahead, an arrangement that could lead to disaster: unsupported, they would be quickly picked off. It was the sheer size of the fleets and the rippling effect of lag times as each ship kept adjusting its position that made these formations so difficult to maintain. Finding the crescent too hard to orchestrate, Ali switched his deployment to a flat line in three divisions that mirrored his opponent’s formation, with the

Sultana

as the front marker; no ship’s commander was to pull ahead, under pain of death. The two fleets closed at a walking pace as they struggled to keep their shape.

What the Christians lacked in maneuverability they made up in firepower. The Spanish Western-style galleys were weightier than their opponents’ and packed a heavier punch. The Christian ships, on average, possessed twice the number of artillery pieces; used judiciously, they could inflict grievous blows. As the slow miles shrank, Ali’s lookouts could see that the Christian center was packed with these heavier Spanish galleys. If not disrupted and outflanked by the Ottoman wings, these could bludgeon his center. This started to cause Ali concern.

And the Christians had been innovating. At Doria’s suggestion Don Juan had ordered his commanders to shear off the rams from the front of their ships. These structures were more ornamental than practical; their removal permitted the guns to be trained lower and to hit the enemy at close range. Galleys could close the last hundred yards faster than gunners could reload, so there would be only one shot. Don Juan was determined to follow Don Garcia’s advice: to keep his nerve and his fire until the last minute, when the enemy was bearing down. He did not want his shots whistling harmlessly overhead. At the same time he ordered nets to be strung along the sides of the ships to entangle and impede would-be boarders.

But it was the Venetians who brought the most radical innovation to the fleet that was now lumbering forward. They had stored for future use the performance of their heavily armed galleon at Preveza in 1538; it had inflicted considerable damage on Barbarossa’s galleys and held them off all day. When the Venetians cranked the arsenal shipyard up for war, they dusted off the hulls of six of their merchant great galleys, cumbersome heavyweight oared ships once used for the now-defunct trade with the Eastern Mediterranean. These galleasses, as they called them, had been reconditioned, heavily gunned, and bulwarked with defensive superstructures. On the morning of October 7 galleys were laboriously towing these floating gun platforms up ahead of the line. The Venetians had a definite purpose in mind.

IT WAS A SUNDAY MORNING.

Far away in Rome, Pius was conducting a fervent mass for Christian victory. In Madrid, Philip went on signing documents and dispatching memoranda to all parts of his farflung empire in between church services. Selim was departing from Istanbul for his capital at Edirne with the usual pomp of a sultan’s progress: a splendid cavalcade of jingling cavalry and plumed janissaries, pages, scribes, civil servants, dog handlers, cooks, and harem favorites. The departure was marked by ill omens: Selim’s turban slipped off twice, and his horse fell; a man hurrying to help him had to be hanged for touching the sultan’s person.

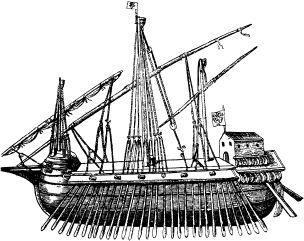

Venetian galleass

In the Gulf of Patras, sometime around midmorning, the wind that had been blowing strongly from the east since dawn, faltered and died. The sea glassed, just a light breeze from the west at Don Juan’s back. The Ottoman fleet promptly dropped its sails; conditions eased for the oarsmen in the Christian fleet. It was taken as a good sign—a wind from God.

Pius had invested the Holy League venture with enormous Christian hope. The banners, the church services, the papal blessings as the ships left port had imparted to the expedition all the religious fervor of a crusade. The pope had asked Don Juan to ensure his men “lived in virtuous and Christian fashion in the galleys, not playing [gambling] or swearing.” Requesen’s private response had been muted. “We will do what we can,” he murmured, casting his eye over the hard-boiled Spanish infantry and the subspecies of Christian humanity chained to the rowing benches. Don Juan had thought it useful to hang a few blasphemers in front of the papal legate at Messina to encourage virtuous behavior. Moral purpose was critical to the success of the whole endeavor. There were priests on every ship; thousands of rosaries were handed to the men; services were held daily. Now, as everyone could see their fate drawing toward them over the calm sea, sober religious dread seized the Christian fleet. Mass was said on every ship with the reminder that there would be no heaven for cowards. The men were confessed of their sins. Immediately afterward, drums and trumpets sounded with cries of “Victory and long live Jesus Christ!”