Emotional Design (19 page)

Authors: Donald A. Norman

The craft of filmmaking encompasses a wide variety of domains. All elements of a film make a difference: story line, pace and tempo, music, framing of the shots, editing, camera position and movement. All come together to form a cohesive, complex experience. A thorough analysis can, and has, filled many books.

All these effects work best, however, when they are unnoticed by the viewer.

The Man Who Wasn't There

(directed and written by the Coen brothers) was filmed in black and white. Roger Deakins, the cinematographer, stated that he wanted black and white rather than color so as not to distract from the story; unfortunately, he fell in love with the power of monochrome images. The film has wonderfully glorious shots, with high dark/light contrast, and in some places spectacular backlighting, all of which I noticed. This is a no-no in film: if you notice it, it is bad. Noticing takes place at the reflective (voyeur's) level, distracting you from that suspension of disbelief so

essential to becoming fully captured by the flow at the behavioral (vicarious) level.

The Man Who Wasn't There

(directed and written by the Coen brothers) was filmed in black and white. Roger Deakins, the cinematographer, stated that he wanted black and white rather than color so as not to distract from the story; unfortunately, he fell in love with the power of monochrome images. The film has wonderfully glorious shots, with high dark/light contrast, and in some places spectacular backlighting, all of which I noticed. This is a no-no in film: if you notice it, it is bad. Noticing takes place at the reflective (voyeur's) level, distracting you from that suspension of disbelief so

essential to becoming fully captured by the flow at the behavioral (vicarious) level.

The story line and engrossing exposition of

The Man Who Wasn't There

enhanced the vicarious pleasure of the film, but noticing the photography caused the voyeuristic pleasure to interrupt with internal commentary (“How did he do that?” “Look at the magnificent lighting,” and so on) and throw the vicarious pleasure off track. Yes, you should be able to go back afterward and marvel at how a film was done, but this should not intrude upon the experience itself.

Video GamesThe Man Who Wasn't There

enhanced the vicarious pleasure of the film, but noticing the photography caused the voyeuristic pleasure to interrupt with internal commentary (“How did he do that?” “Look at the magnificent lighting,” and so on) and throw the vicarious pleasure off track. Yes, you should be able to go back afterward and marvel at how a film was done, but this should not intrude upon the experience itself.

Overslept, woke at 8:00. Only time for a quick coffee before the carpool arrives. The kitchen is disgusting, didn't clean up after last night's little party. Need a bath, but no time (the bathroom's flooded anyway from the broken sink I never got around to fixing). Got to work late and in horrible shape, was demoted as a result. Got home at 5:00, the repo man promptly showed up and repossessed my television because I forgot to pay my bills. My girlfriend won't speak to me because she saw me flirting with the neighbor last night.

Did you realize that this quotation is the description of a game? Not only does it feel like real life, but a bad life at that. Why would anyone think it was a game? Aren't games supposed to be fun? Well, not only is it a description of a game, it is a best-selling one called “The Sims.” Will Wright, the designer and inventor of the Sims, explained that this was a typical day in the life of a game character, as developed by a beginning player.

The Sims is an interactive simulated-world game, otherwise known as a “God” game or sometimes “simulated life.” The player acts like a god, creating characters, populating their world with houses, appliances, and activities. In this game, the player does not control what the game characters do. Instead, the player can only set up the environment

and make high-level decisions. The characters control their own lives, although they have to live within the environment and high-level rules established by the player. The result is quite often not at all what their god intended them to do. The quotation is one example of a character unable to cope within the world its god created. But, says Wright, as the player's skill at creating worlds improves, the character might be able to spend the end of each day “sipping mint-juleps by the pool.”

and make high-level decisions. The characters control their own lives, although they have to live within the environment and high-level rules established by the player. The result is quite often not at all what their god intended them to do. The quotation is one example of a character unable to cope within the world its god created. But, says Wright, as the player's skill at creating worlds improves, the character might be able to spend the end of each day “sipping mint-juleps by the pool.”

Wright explains the problem like this:

The Sims is really just a game about life. Most people don't consciously realize how much strategic thinking goes into everyday, minute-to-minute living. We're so used to doing it that it submerges into our subconscious as a background task. But each decision you make (which door to go through? where to eat lunch? when to go to bed?) is calculated at some level to optimize something (time, happiness, comfort). This game takes that internal process and makes it external and visible. One of the first things players usually do in the game is to recreate their family, home, and friends. Then they're playing a game about themselves, sort of a strange, surreal mirror of their own lives.

Play is a common activity, engaged in by many animals and, of course, by us humans. Play serves many purposes. It probably is good practice for many of the skills required later in life. It helps children develop the mix of cooperation and competition required to live effectively in social groups. In animals, play helps establish their social dominance hierarchy. Games are more organized than play, usually with formal or, at least, agreed-upon rules, with some goal and usually some scoring mechanism. As a result, games tend to be competitive, with winners and losers.

Sports are even more formally organized than games, and at the professional level, are as much for the spectator as the player. As a result, an analysis of spectator sports is somewhat akin to that of movies, where the experience is vicarious and as a voyeur.

Of all the varieties of play, games, and sports, perhaps the most exciting new development is that of the video game. This is a new genre for entertainment: literature, film, game playing, sports, interactive novel, storytellingâall of these, but more besides.

Video games were once thought of as a mindless sport for teenage boys. No more. They are now played all around the world, including slightly more than half the population of the United States. They are played by everyone: from children to mature adults, with the average age of a player around thirty, and the gender difference evenly split between men and women. Video games come in many genres. In

The Medium of the Video Game

, Mark Wolf identifies forty-two different categories:

The Medium of the Video Game

, Mark Wolf identifies forty-two different categories:

Abstract, Adaptation, Adventure, Artificial Life, Board Games, Capturing, Card Games, Catching, Chase, Collecting, Combat, Demo, Diagnostic, Dodging, Driving, Educational, Escape, Fighting, Flying, Gambling, Interactive Movie, Management Simulation, Maze, Obstacle Course, Pencil-and-Paper Games, Pinball, Platform, Programming Games, Puzzle, Quiz, Racing, Role-Playing, Rhythm and Dance, Shoot 'Em Up, Simulation, Sports, Strategy, Table-Top Games, Target, Text Adventure, Training Simulation, and Utility.

Video games are a mixture of interactive fiction with entertainment. During the twenty-first century, they promise to evolve into radically different forms of entertainment, sport, training, and education. Many games are fairly elementary, simply putting a player in some role where fast reflexesâand sometimes great patienceâare required to traverse a relatively fixed set of obstacles in order to move up the levels either to obtain a total game score or to accomplish some simple goal (“rescue the beleaguered princess and save her kingdom”). But wait. The story lines are getting ever-more complex and realistic, the demands upon the player more reflective and cognitive, less visceral and fast motor responses. The graphics and sound are getting so good that simulator games can be used for real

training, whether flying an airplane, operating a railroad, or driving a race car or automobile. (The most elaborate video games are the full-motion airplane simulators used by the airlines that are so accurate that they enable pilots to be certified to fly passenger planes without ever flying the actual aircraft. But don't call these “games”; they are taken very seriously, and some of them can cost as much as the airplane itself.)

training, whether flying an airplane, operating a railroad, or driving a race car or automobile. (The most elaborate video games are the full-motion airplane simulators used by the airlines that are so accurate that they enable pilots to be certified to fly passenger planes without ever flying the actual aircraft. But don't call these “games”; they are taken very seriously, and some of them can cost as much as the airplane itself.)

Today's sales of video games approachâand, in some cases, surpassâbox-office receipts of movies. And we are still in the early days of video games. Imagine what they will be like in ten or twenty years. In an interactive game what happens in a story depends as much upon your actions as on the plot set up by the author (designer). Contrast this with a movie, where you have no control over the events. As a result, when experienced game players watch a movie, they miss this control, feeling as if they are “stuck watching a one-way plot.” Moreover, the sense of involvement, the flow state, is much more intense in games than in most movies. In movies, you sit at a distance watching events unfold. In a video game, you are an active participant. You are part of the story, and it is happening to you, directly. As Verlyn Klinkenborg says, “what underlies it all is that visceral sense of having walked through a door into another universe.”

The interactive, controlling part of video games is not necessarily superior to the more rigid, fixed format of books, theater, and film. Instead, we have different types of experiences, both of which are desirable. The fixed formats let master storytellers control the events, guiding you through the events in a carefully controlled sequence, very deliberately manipulating your thoughts and emotions until the climax and resolution. You surrender yourself quite voluntarily to this experience, both for the enjoyment and for the lessons that might be learned about life, society, and humanity. In a video game, you are an active participant, and as a result, the experience may vary from time to timeâdull, boring, frustrating during one session; exciting, invigorating, rewarding during another. The lessons to be learned will vary depending upon the exact sequence of events that occurred and

whether or not you were successful. Books and films clearly have a permanent role in society, as do games, video or otherwise.

whether or not you were successful. Books and films clearly have a permanent role in society, as do games, video or otherwise.

Books, theater, movies, and games all occupy a fixed period of time: there is a beginning, then an end. This is not so of life. Sure, birth marks the beginning and death the end, but from your everyday perspective, life is ongoing. It continues even when you sleep or travel. Life cannot be escaped. When you go away, you return to find out what has transpired in your absence (during those moments when you were not in touch via messaging, email, or telephone). Video games are becoming like life.

Video games used to involve single individuals. This will always be a viable genre, but more and more, these games are involving groups, sometimes scattered across the world, communicating through computer networks. Some are on-line, real-time activities, such as sports, games, conversations, entertainment, music, and art. But some are environments, simulated worlds with people, families, households, and communities. In all of these, life goes on even when you, the player, are not present.

Some games have already tried to reach out toward their human players. If you, the player, create a family in a “god” game, nurturing your invented characters over an extended duration, perhaps months or even years, what happens when a family member needs help while you are asleep, or at work, school, or play? Well, if the crisis is severe enough, your game-family member will do just what a real family member would do: contact you by telephone, fax, email, or whatever form works. Someday one might even contact your friends, asking for help. So don't be surprised if a co-worker interrupts you in an important business meeting to say that your game character is in trouble: it is in urgent need of your assistance.

Yes, video games are an exciting new development in entertainment. But they may turn out to be far more than entertainment. The artificial may cease to be distinguishable from the real.

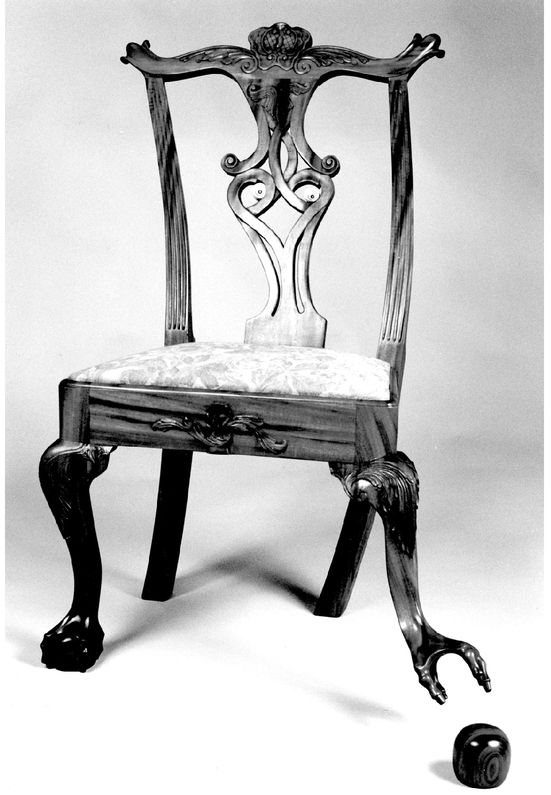

FIGURE 5.1

Oops! Uh oh, the poor chair.

Oops! Uh oh, the poor chair.

It lost its ball, and it doesn't want anyone to know! Look how quietly it's sneaking out its foot, hoping to get it back before anyone notices.

(Renwick Gallery; image courtesy of Jake Cress, cabinetmaker.)

CHAPTER FIVE

People, Places, and Things

“UH OH, THE POOR CHAIR has lost its ball and doesn't want anyone to know.” To me, the most interesting thing about the chair in

figure 5.1

is that my reaction upon viewing “the poor chair” is perfectly sensible. Certainly I don't believe the chair is animate, that it has a brain, let alone feelings and beliefs. Yet there it is, clearly sneaking out its foot, hoping nobody will notice. What is going on?

figure 5.1

is that my reaction upon viewing “the poor chair” is perfectly sensible. Certainly I don't believe the chair is animate, that it has a brain, let alone feelings and beliefs. Yet there it is, clearly sneaking out its foot, hoping nobody will notice. What is going on?

This is an example of our tendency to read emotional responses into anything, animate or not. We are social creatures, biologically prepared to interact with others, and the nature of that interaction depends very much on our ability to understand another's mood. Facial expressions and body language are automatic, indirect results of our affective state, in part because affect is closely tied to behavior. Once the emotional system primes our muscles in preparation for action, other people can interpret our internal states by looking at how tense or relaxed we are, how our face changes, how our limbs moveâ

in short, our body language. Over millions of years, this ability to read others has become part of our biological heritage. As a result, we readily perceive emotional states in other people and, for that matter, anything that is at all vaguely lifelike. Hence our reaction to

figure 5.1

: the chair's posture is so compelling.

in short, our body language. Over millions of years, this ability to read others has become part of our biological heritage. As a result, we readily perceive emotional states in other people and, for that matter, anything that is at all vaguely lifelike. Hence our reaction to

figure 5.1

: the chair's posture is so compelling.

We have evolved to interpret even the most subtle of indicators. When we deal with people, this faculty is of huge value. It is even useful with animals. Thus, we can often interpret the affective state of animalsâand they can interpret ours. This is possible because we share common origins for facial expression, gesture, and body posture. Similar interpretations of inanimate objects might seem bizarre, but the impulse comes from the same sourceâour automatic interpretive mechanisms. We interpret everything we experience, much of it in human terms. This is called anthropomorphism, the attribution of human motivations, beliefs, and feelings to animals and inanimate things. The more behavior something exhibits, the more we are apt to do this. We are anthropomorphic toward animals in general, especially our pets, and toward toys such as dolls, and anything we may interact with, such as computers, appliances, and automobiles. We treat tennis rackets, balls, and hand tools as animate beings, verbally praising them when they do a good job for us, blaming them when they refuse to perform as we had wished.

Other books

The Artificial Silk Girl by Irmgard Keun

Feint of Heart by Aimee Easterling

Graveminder by Melissa Marr

Fight for Her#3 by Jj Knight

Unseen Academicals by Terry Pratchett

The Last Kiss by Murphy, M. R.

The Amber Room by Berry, Steve

A Pain in the Tuchis: A Mrs. Kaplan Mystery by Mark Reutlinger

The Unseen by Hines

The Transmigration of Bodies by Yuri Herrera