Einstein (105 page)

Authors: Walter Isaacson

Einstein went in to work at the Institute the next day, but he had a pain in his groin and it showed on his face. Is everything all right? his assistant asked. Everything is all right, he replied, but I am not.

He stayed at home the following day, partly because the Israeli consul was coming and partly because he was still not feeling well. After the visitors left, he lay down for a nap. But Dukas heard him rush to the

bathroom in the middle of the afternoon, where he collapsed. The doctors gave him morphine, which helped him sleep, and Dukas set up her bed right next to his so that she could put ice on his dehydrated lips throughout the night. His aneurysm had started to break.

24

A group of doctors convened at his home the next day, and after some consultation they recommended a surgeon who might be able, though it was thought unlikely, to repair the aorta. Einstein refused. “It is tasteless to prolong life artificially,” he told Dukas. “I have done my share, it is time to go. I will do it elegantly.”

He did ask, however, whether he would suffer “a horrible death.” The answer, the doctors said, was unclear. The pain of an internal hemorrhage could be excruciating. But it may take only a minute, or maybe an hour. To Dukas, who became overwrought, he smiled and said, “You’re really hysterical—I have to pass on sometime, and it doesn’t really matter when.”

25

Dukas found him the next morning in agony, unable to lift his head. She rushed to the telephone, and the doctor ordered him to the hospital. At first he refused, but he was told he was putting too much of a burden on Dukas, so he relented. The volunteer medic in the ambulance was a political economist at Princeton, and Einstein was able to carry on a lively conversation with him. Margot called Hans Albert, who caught a plane from San Francisco and was soon by his father’s bedside. The economist Otto Nathan, a fellow German refugee who had become his close friend, arrived from New York.

But Einstein was not quite ready to die. On Sunday, April 17, he woke up feeling better. He asked Dukas to get him his glasses, papers, and pencils, and he proceeded to jot down a few calculations. He talked to Hans Albert about some scientific ideas, then to Nathan about the dangers of allowing Germany to rearm. Pointing to his equations, he lamented, half jokingly, to his son, “If only I had more mathematics.”

26

For a half century he had been bemoaning both German nationalism and the limits of his mathematical toolbox, so it was fitting that these should be among his final utterances.

He worked as long as he could, and when the pain got too great he went to sleep. Shortly after one a.m. on Monday, April 18, 1955, the nurse heard him blurt out a few words in German that she could not

understand. The aneurysm, like a big blister, had burst, and Einstein died at age 76.

At his bedside lay the draft of his undelivered speech for Israel Independence Day. “I speak to you today not as an American citizen and not as a Jew, but as a human being,” it began.

27

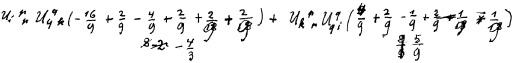

Also by his bed were twelve pages of tightly written equations, littered with cross-outs and corrections.

28

To the very end, he struggled to find his elusive unified field theory. And the final thing he wrote, before he went to sleep for the last time, was one more line of symbols and numbers that he hoped might get him, and the rest of us, just a little step closer to the spirit manifest in the laws of the universe.

EINSTEIN’S BRAIN AND EINSTEIN’S MIND

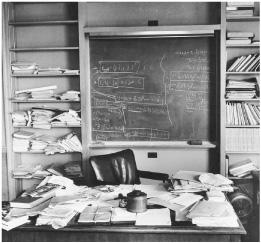

Einstein’s study, as he left it

When Sir Isaac Newton died, his body lay in state in the Jerusalem chamber of Westminster Abbey, and his pallbearers included the lord high chancellor, two dukes, and three earls. Einstein could have had a similar funeral, glittering with dignitaries from around the world. Instead, in accordance with his wishes, he was cremated in Trenton on the afternoon that he died, before most of the world had heard the news. There were only twelve people at the crematorium, including Hans Albert Einstein, Helen Dukas, Otto Nathan, and four members of the Bucky family. Nathan recited a few lines from Goethe, and then took Einstein’s ashes to the nearby Delaware River, where they were scattered.

1

“No other man contributed so much to the vast expansion of 20th

century knowledge,” President Eisenhower declared. “Yet no other man was more modest in the possession of the power that is knowledge, more sure that power without wisdom is deadly.” The

New York Times

ran nine stories plus an editorial about his death the next day: “Man stands on this diminutive earth, gazes at the myriad stars and upon billowing oceans and tossing trees—and wonders. What does it all mean? How did it come about? The most thoughtful wonderer who appeared among us in three centuries has passed on in the person of Albert Einstein.”

2

Einstein had insisted that his ashes be scattered so that his final resting place would not become the subject of morbid veneration. But there was one part of his body that was not cremated. In a drama that would seem farcical were it not so macabre, Einstein’s brain ended up being, for more than four decades, a wandering relic.

3

Hours after Einstein’s death, what was supposed to be a routine autopsy was performed by the pathologist at Princeton Hospital,Thomas Harvey, a small-town Quaker with a sweet disposition and rather dreamy approach to life and death. As a distraught Otto Nathan watched silently, Harvey removed and inspected each of Einstein’s major organs, ending by using an electric saw to cut through his skull and remove his brain. When he stitched the body back up, he decided, without asking permission, to embalm Einstein’s brain and keep it.

The next morning, in a fifth-grade class at a Princeton school, the teacher asked her students what news they had heard. “Einstein died,” said one girl, eager to be the first to come up with that piece of information. But she quickly found herself topped by a usually quiet boy who sat in the back of the class. “My dad’s got his brain,” he said.

4

Nathan was horrified when he found out, as was Einstein’s family. Hans Albert called the hospital to complain, but Harvey insisted that there may be scientific value to studying the brain. Einstein would have wanted that, he said. The son, unsure what legal and practical rights he now had in this matter, reluctantly went along.

5

Soon Harvey was besieged by those who wanted Einstein’s brain or a piece of it. He was summoned to Washington to meet with officials of the U.S. Army’s pathology unit, but despite their requests he refused to show them his prized possession. Guarding it had become a mission.

He finally decided to have friends at the University of Pennsylvania turn part of it into microscopic slides, and so he put Einstein’s brain, now chopped into pieces, into two glass cookie jars and drove it there in the back of his Ford.

Over the years, in a process that was at once guileless as well as bizarre, Harvey would send off slides or chunks of the remaining brain to random researchers who struck his fancy. He demanded no rigorous studies, and for years none were published. In the meantime, he quit Princeton Hospital, left his wife, remarried a couple of times, and moved around from New Jersey to Missouri to Kansas, often leaving no forwarding address, the remaining fragments of Einstein’s brain always with him.

Every now and then, a reporter would stumble across the story and track Harvey down, causing a minor media flurry. Steven Levy, then of

New Jersey Monthly

and later of

Newsweek,

found him in 1978 in Wichita, where he pulled a Mason jar of Einstein’s brain chunks from a box labeled “Costa Cider” in the corner of his office behind a red plastic picnic cooler.

6

Twenty years later, Harvey was tracked down again, by Michael Paterniti, a free-spirited and soulful writer for

Harper’s,

who turned his road trip in a rented Buick across America with Harvey and the brain into an award-winning article and best-selling book,

Driving Mr. Albert.

Their destination was California, where they paid a call on Einstein’s granddaughter, Evelyn Einstein. She was divorced, marginally employed, and struggling with poverty. Harvey’s perambulations with the brain struck her as creepy, but she had a particular interest in one secret it might hold. She was the adopted daughter of Hans Albert and his wife Frieda, but the timing and circumstances of her birth were murky. She had heard rumors that made her suspect that possibly, just possibly, she might actually be Einstein’s own daughter. She had been born after Elsa’s death, when Einstein was spending time with a variety of women. Perhaps she had been the result of one of those liaisons, and he had arranged for her to be adopted by Hans Albert. Working with Robert Schulmann, an early editor of the Einstein papers, she hoped to see what could be learned by studying the DNA from Einstein’s brain.

Unfortunately, it turned out that the way Harvey had embalmed the brain made it impossible to extract usable DNA. And so her questions were never answered.

7

In 1998, after forty-three years as the wandering guardian of Einstein’s brain, Thomas Harvey, by then 86, decided it was time to pass on the responsibility. So he called the person who currently held his old job as pathologist at Princeton Hospital and went by to drop it off.

8

Of the dozens of people to whom Harvey doled out pieces of Einstein’s brain over the years, only three published significant scientific studies. The first was by a Berkeley team led by Marian Diamond.

9

It reported that one area of Einstein’s brain, part of the parietal cortex, had a higher ratio of what are known as glial cells to neurons. This could, the authors said, indicate that the neurons used and needed more energy.

One problem with this study was that his 76-year-old brain was compared to eleven others from men who had died at an average age of 64. There were no other geniuses in the sample to help determine if the findings fit a pattern. There was also a more fundamental problem: with no ability to trace the development of the brain over a lifetime, it was unclear which physical attributes might be the

cause

of greater intelligence and which might instead be the

effect

of years spent using and exercising certain parts of the brain.

A second paper, published in 1996, suggested that Einstein’s cerebral cortex was thinner than in five other sample brains, and the density of his neurons was greater. Once again, the sample was small and evidence of any pattern was sketchy.

The most cited paper was done in 1999 by Professor Sandra Witelson and a team at McMaster University in Ontario. Harvey had sent her a fax, unprompted, offering samples for study. He was in his eighties, but he personally drove up to Canada by himself, transporting a hunk that amounted to about one-fifth of Einstein’s brain, including the parietal lobe.

When compared to brains of thirty-five other men, Einstein’s had a much shorter groove in one area of his inferior parietal lobe, which is thought to be key to mathematical and spatial thinking. His brain was

also 15 percent wider in this region. The paper speculated that these traits may have produced richer and more integrated brain circuits in this region.

10

But any true understanding of Einstein’s imagination and intuition will not come from poking around at his patterns of glia and grooves. The relevant question was how his

mind

worked, not his brain.

The explanation that Einstein himself most often gave for his mental accomplishments was his curiosity. As he put it near the end of his life, “I have no special talents, I am only passionately curious.”

11

That trait is perhaps the best place to begin when sifting through the elements of his genius. There he is, as a young boy sick in bed, trying to figure out why the compass needle points north. Most of us can recall seeing such needles swing into place, but few of us pursue with passion the question of how a magnetic field might work, how fast it might propagate, how it could possibly interact with matter.