Eat Him If You Like (4 page)

Read Eat Him If You Like Online

Authors: Jean Teulé

Having dared to think that the worst was over and everything would turn out fine, Alain began to realise that nothing was further from the truth.

âHold your horses! You can't do that!' exclaimed a

cheese-maker

from Jonzac.

âHe's the reason for our misfortune!' clamoured the crowd, giving voice to the cheese-maker's unspoken accusation.

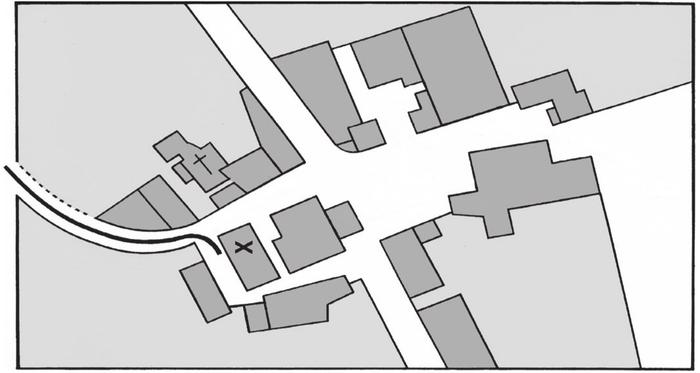

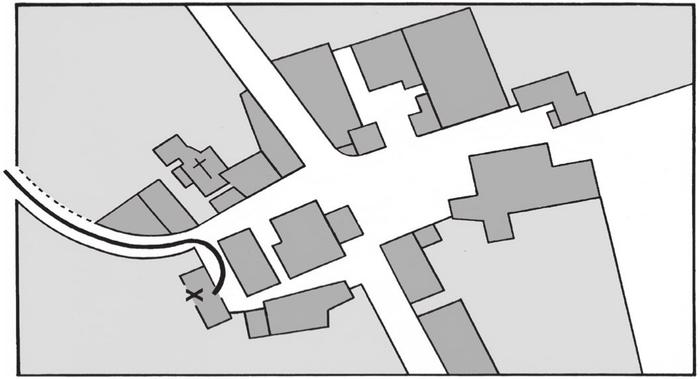

Angry men flocked over from the priest's garden, the donkey and pig markets, and the inns at the centre of the village. Rioters were spreading the news.

âWe found a Prussian at the fair!'

âA Prussian?'

Suddenly, insults rained down on Alain from all sides like a violent thunderstorm. He was afraid â this was not the roar of acclaim. They launched into a furious fresh attack, like an army. The men wore smocks and hats; the women had chignons, coarse skirts, and scarves on their heads.

âHurry, hurry! Get the Prussian! Get the Prussian!'

At the side of the road, people were stealing from the priest's wood pile in order to arm themselves with âstout sticks'. At least three hundred people had gathered, all with sticks, scythes and pitchforks. Once again, Alain was showered with blows. Bouteaudon, the Connezac miller, had his arms protectively round Alain. People hit him too and eventually he was forced to lay Alain on the ground.

The villagers' previous love and affection had turned to hate. Kneeling, Alain almost laughed to himself between the blows and his tears. It was as though earlier they had eased off the pressure for a moment, and granted his protectors some time, all the better to savour this renewed attack. Chaos reigned and there was a lust for blood.

âWe don't want a Judas in Hautefaye! He must be killed!'

The net of hostile rumours was closing in. It was easy to believe this was a game at the funfair â knocking down skittles, climbing the greasy pole, a carousel ride, a sack race, or a more modern velocipede race. Old Moureau left his cockerel-stoning stall and kicked Alain so violently in the head that he dislodged a clump of hair. He rejoined the others and showed them the tip of his bloodied shoe, covered in hair.

âBull's eye.'

âBravo, you've won a cockerel!' shouted the villagers.

âYou stupid old fool. You'd do better to think of the day when you'll have to account for yourself!' shouted Dubois, outraged, pointing his finger at the old man.

âThink what you will, good people, but things are not what they seem. I'm not a Prussian â¦' Alain reminded them in vain, struggling to sit up and protect his head. He was at the centre of a comedy of errors. Public condemnation wounded him with the prongs of pitchforks. What a regrettable state of affairs! Even fourteen-year-old Thibassou derived a perverse pleasure from hitting him, and he asked around for a big knife.

Alain's protectors struggled to help him over the few yards that now separated them from the narrow alley where the mayor's residence stood, opposite his smithy. The goat shed was just ahead.

âBernard Mathieu! Bernard Mathieu!'

Three steps led up to the door of the house, which served as the town hall on council evenings and election days. The door opened and a burly man in his sixties emerged, chewing and wiping his hands on his tricolour sash, tied round his chest much like a napkin. He paused and observed Antony and Dubois with a frown as they brought Alain towards him.

âYour Worship, Your Worship! Look how people are attacking Monsieur de Monéys! We must protect him! Let him in!'

Suddenly the crowd surged into the lane, with hundreds of people clamouring to assault Alain amid a torrent of abuse. Faced with their caterwauling and whistling, Bernard Mathieu hurriedly turned and went back up the steps.

Mazerat lost patience with the mayor's dithering.

âMayor, do something quickly! These men are mad! You know Monsieur de Monéys!'

âI know him, I know him ⦠He's not from the village.'

Alain tried to protect himself with his forearms but, standing there forlornly in his tattered clothes, he did not have the strength.

âBut, Bernard Mathieu, you must help us save him. What will happen if you don't?'

âWhat do you expect me to do with no police back-up? Who are these folks attacking him? Outsiders?' stuttered the mayor.

âYou know them all! Look, there's Campot, Léchelle, Frédérique and everyone else. Order them to leave Alain alone.'

âHey! You there! It's over. Do you hear me? Leave this man alone. If he needs punishing, call in the law,' said Bernard Mathieu, descending two steps.

âWe are the law!' shouted Roumaillac.

âA law of fools!' commented Antony.

âYour Worship, I implore you, let him in!' begged Mazerat.

But the mayor's wife at the open window by the front door refused.

âSo that they can come and smash our crockery? Whatever next? Bernard, come back and finish your dinner!' she commanded, resting her hands on the shoulders of her eight-year-old granddaughter, who was sobbing in panic at the sight of the fists and sticks raining down on Alain in a swirl of light, dust and mist.

âAlain, go and play somewhere else; you're making my little granddaughter cry,' requested the mayor, ever the attentive grandfather.

âI don't believe it. The mayor ⦠This is outrageous,' said Bouteaudon, devastated.

âWhat are you going to do, Bernard?' asked Antony.

âFinish my supper.'

Alain looked over at the dwelling he was not allowed to enter. Behind the mayor, he could make out one bed, a broken sideboard and four chairs. The curtains at the window had once been white but were now spattered with squashed bugs. Hautefaye's mayor closed the door on the ugly, faded decor. A key turned twice in the lock. The mayor's moustachioed nephew, Georges, who was a baker in Beaussac, banged on the shutters that his aunt had just closed.

âAunt! Uncle! Open up, if only for Monsieur de Monéys! We must protect him!'

âIt's none of our business!'

Driven back against the wall, Alain appealed softly to the brutes.

âMy friends, you're mistaken. I'm ready to suffer for France â¦'

âYou'll suffer all right; we'll make sure you suffer!' said François Chambort, a blacksmith from Pouvrières, grabbing Alain by the hair. As children, they had fished for crayfish together. Alain was hurt to see his former playmate hatching some grisly plan right in front of his eyes, something vicious and relentless. François blew noisily on his hat and commanded in a cattle drover's voice, âTake the Prussian

over the road to the smithy! I know what we can do! We can tie him to the frame and shoe him like a horse!'

The Campot brothers dragged Alain to the smithy. Buisson and Mazière kicked him in the shins to hurry him along. Chambort was shouting out orders. The crowd surged forward.

âCastrate him while you're at it, the son of a bitch. Then he won't defile our women,' bayed Madame Lachaud.

They successfully manoeuvred Alain between the four posts of the frame used to restrain horses. Lying on his back between the wooden bars, his hands and feet bound, Alain shouted feebly, âLong live the Emperor!' Men surrounded him, pressing in. The ordeal was endless. Straps and ropes were tightened, constricting his chest and throat. He choked. He struggled, his legs flailing wildly. Duroulet, a labourer

from Javerlhac, pulled off Alain's brown boots and another man removed his purple silk socks. In the crowd, Lamongie â a stocky farmer with ginger hair â was brandishing a huge pair of pliers. Alain had known him as a boy; they had raided magpies' nests together.

âWe'll clip the Prussian's hooves for him!' he said.

A puffed-up turkey fled between people's legs, flapping its wings. Lamongie gripped the lower part of Alain's big toe with his pincers and pulled as though he were extracting a nail from a wall. He staggered backwards, holding the toe in his pincers. Alain howled. The crowd sniggered. Chambort took Lamongie's place and held a horseshoe to the sole of Alain's lame foot. Suddenly, he banged in a nail with a single stroke, shattering his heel. The other

twenty-six

bones in Alain's foot seemed to splinter too. The pain rose to his knee, his groin and then tore into his chest, suffocating him. His shoulders tensed and he thought his head would explode. Chambort nailed a second shoe to the other foot. Alain's head jerked backwards, his eyes rolling. Memories surged into his mind. He felt like a ship being stormed by pirates shouting, âDirty beast!'

His body was weak and weary and his heels throbbed. The noise was deafening. His flesh was turning a ghastly colour. Alain was living a nightmare. The behaviour of his fellow creatures plunged him into despair. Earlier, on his way to the fair and unaware of the horrific fate that awaited him, he had been lost in the most wonderful reverie. Now, even the devil would have cried for mercy on seeing several of Alain's toes fly from Lamongie's pliers and hurtle through the air.

The schoolmaster's wife was pulling faces at the window, sticking out her tongue and slobbering on the grimy glass.

âHurry!' shouted a voice. âHurry, drinks are on the priest! We've finished off the cheap communion wine, so now he's bringing vintage bottles up from the cellar. Everyone's invited!'

âFirst I must finish clipping the Prussian's hooves,' said Lamongie.

âWe'll come back! Come and have a drink. Let him suffer. He won't go far trussed up like that. Volunteers can keep watch by the door while we wet our whistles. The priest has even opened his house and the church to hold more people. Come sit on the altar and get sozzled!'

The crowd went off, leaving Alain. He heard the door creak behind them. Five men, who must have crept around the outside of the smithy, stole into the room. There they found Alain covered in blood, still tied up, with horseshoes on his feet. He had no toes on his right foot. He was sure they would no longer want him in the army now, even on the Lorraine front. The men who had been keeping watch left to get drunk with the others.

Mazerat and the mayor's nephew made the most of the guards' absence. âQuick, let's free him. Those fools haven't tied him up properly.'

Mazerat opened a penknife and sawed at the knots. Distraught, Antony propped Alain up and supported his bleeding head, cradling him and trying to comfort him, as far as it is possible to comfort a man in such a predicament.

âHold firm, Alain! We'll get you out of here.'

âIs that you, Pierre?'

âYes, it's me. They're monsters. They should be locked up.'

âThey know not what they do.'

Bouteaudon crouched down and cupped Alain's face in his gentle miller's hands. Miraculously, Alain seemed to be smiling. Dubois took out a handkerchief and dabbed at Alain's brow, which was covered in sweat and dust. He even wiped the dried blood from Alain's eyes, so that he could open them again. Alain was finding it difficult to catch his breath, but the presence of his solicitous friends gave him new hope.

âWe must tell my mother that I'll be back later than expected â¦'

Antony looked at him sadly. He was a good, simple man and a loyal friend, and it pained him to see Alain being treated this way. Suddenly young Thibassou burst into the smithy. He grabbed a large knife from the workbench and ran off towards the church, shouting, âQuick! Quick! They've freed the Prussian!'

Mazerat and Bouteaudon slipped their heads under Alain's armpits to support him.

âThat little bastard! Where can we take Monsieur de Monéys?' they groaned.

âTo Mousnier's place,' suggested Antony. âWhen he had to do some work on the inn, Alain lent him the money he needed interest free. He'll take him in.'

But they had barely left the smithy, heading for the town centre, when the mob arrived from the vicarage and barred their path.

âLeave him to us!' they shouted.

âThis is Alain de Monéys!' Dubois reminded them. âHe has never wronged anyone! He's the only man in these parts who'll let you gather wood in his forests if you're short for the winter! And you can run after hares in his meadows without him setting his dogs on you!'

âShut up, idiot!' bellowed Antoine Léchelle, grabbing Dubois by his shirt.

âCut off his balls!' shrieked Madame Lachaud. Arms knocked Alain to his knees just below the mayor's window, which opened. The son of the Fayemarteau roofer, whom Alain had wanted to hire, whacked him in the face with a stick.

âRoland! You've just hit your father's friend!' exclaimed Antony.

âMy father has no Prussian friends! Oh, look, here he is. Tell them, Father!'

His father, drunk on holy wine, raised his iron bar. Alain looked at him and said, âPierre Brut, it's me, I was hoping you would fix a barn roof â¦' But the roofer was deaf and blind to his pleas and hit him with all his strength. Others lashed his back and legs. With horseshoes on his feet and several toes missing, he stumbled and collapsed under the hail of metal blows.

âSee the Prussian dance!' jeered the mob.

The mayor's nephew once again implored his uncle to give Alain shelter. From the window, Bernard Mathieu pointed to the sheep barn at the end of the lane.

âPut him in there. He'll be just as comfortable there as in my house until you can take him back to Bretanges.'