Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir (15 page)

Read Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir Online

Authors: Jimmie Walker,Sal Manna

My job on

Good Times

was to get laughs. With the series dealing with so many very difficult subjects, J. J. was the comic relief, the color in the Evans family’s otherwise drab existence.

In sitcoms someone has to take the pie in the face. If no one takes the pie, there is no comedy. If every character is earnest, there is nothing to laugh at. Sometimes that character is the star, sometimes it is a lesser character, but his or her role is a constant—take the pie.

I Love Lucy

? Lucy.

Mary Tyler Moore

? Ted.

Honeymooners

? Norton.

All in the Family

? Meathead.

Seinfeld

? George.

The Andy Griffith Show

? Barney.

Taxi

? Louie.

Cheers

? Cliff.

M*A*S*H

? Klinger.

Friends

? Joey. There are exceptions—such as the

Cosby Show

of the ’80s. But just like with his stand-up, Cosby is in a class by himself.

On

Good Times

, J. J. took the pie. The writers did not have to elaborate. The script would read, “J. J. reacts,” and I would do my thing.

I was Kid Dyn-o-mite! But for some, including members of the cast, I was taking too much of the pie.

Bad times were about to come to

Good Times

.

6

I Am Not J. J.

THE BIGWIGS AT THE MOVIE AND TV STUDIOS WERE NOT AWARE OF it, but there were many, many days during the run of

Good Times

when there was more comedy talent on the bottom floor of my three-story condo on Burton Way in Beverly Hills than anywhere else in Hollywood.

Sitting on the couch would be David Letterman next to Jay Leno next to Paul Mooney. Snacking on the food might be Robert Schimmel, Richard Jeni, Louie Anderson, and Elayne Boosler. Young Byron Allen would be trying to ignore the fact that his mother was in the kitchen waiting to drive him home. There were others whose names would never be recognizable to the public because they were not star performers, such as Wayne Kline, Marty Nadler, Jeff Stein, Jack Handey, Steve Oedekirk, and Larry Jacobson, but who would soon write for some of the most popular sitcoms and late-night talk shows in television history. All of them—all then unknowns—would gather at my home from one to five times a week because they were on my writing staff, commissioned to pen jokes for my stand-up act.

I was good enough as a stand-up to, well, stand up on my own—without J. J. Don’t get me wrong. It was a combination of luck and being at the right place at the right time that brought me to J. J. and

Good Times

. I’m grateful for that. But I was and would continue to be a stand-up comic.

Building that career was where I put all my energies. So I was always in need of jokes. Wherever there are stand-up comedians, there are comedy writers who give them many of their jokes. There have been and remain few comics who write anywhere close to all of their own material—no matter what the public perception might be (Cosby, once again, being one of those exceptions). Being funny and new as often as you need to be on stage is just too hard.

Everywhere a comic goes, people come up and say, “I’ve got a joke for you.” They are almost always surprised when you do not seem that interested in hearing it. We are not trying to be rude, but we get a lot of jokes from a lot of people who make their living writing jokes. We hear jokes all day, every day. We do not need help with our jokes. We have help from the best comedy writers on the planet. They do this for a living.

To those who create it, comedy is not a joke. Comedy is serious. In my early days a Phil Foster might give me a line for my debut on the

Paar

show or friends like Landesberg or Nadler might feed me jokes over coffee at 2 a.m. at the Camelot. Thanks to a decent steady paycheck from

Good Times

I could afford to pay a staff of hungry writers. Thanks to the show, I was offered more and better-paying stand-up gigs too. I was off the chitlin’ circuit and into Mr. Kelly’s in Chicago, the hungry i in San Francisco, the Copacabana in New York. Except for one year during the show’s six seasons, I made more money from those gigs than from CBS. But the only way to keep up both the volume and the quality of the jokes I would lay on audiences was to have a staff of writers.

Success paid for them, but success also made them necessary. When no one knew who I was, much of my material came from observing everyday life. I could walk around in the general public and interact with people. But once I made a name for myself and was instantly recognizable, that was no longer possible. When you come into people’s living rooms every week and then they see you in person, they can’t believe you escaped from the TV! Instead of being able to listen in on conversations,

I

was the conversation. Instead of being the watcher, I was the watchee. I needed access to the eyes and ears of less visible comedians.

I knew Leno from our days in New York. He had moved to the West Coast and was establishing a beachhead at the Comedy Store. But no one was being paid there. He could pick up $150 a week working on jokes for me. He also told me about a friend of his, Gene Braunstein, a former classmate at Emerson College in Boston where their comedy team Gene and Jay played area coffeehouses. Leno asked if Gene could join our meetings and I said yes. Braunstein aka the Mighty Mister Geno quickly became my comedy coordinator.

I received my

Good Times

script on a Thursday or Friday. Mister Geno and I would get together on Saturday morning and run it for two or three hours—however long it took for me to memorize my lines. I wanted to have the script down pat so when I did my stand-up that night at the Store, I would not be distracted worrying about my “other job,” the one at CBS.

During the week, as soon as I left the

Good Times

set in the afternoon, I jumped into my car and headed for a Chinese take-out place, where I would grab some food and phone Mister Geno. I would tell him I was on my way and then call one or more girlfriends to pick up pizzas, sandwiches, and sodas for everyone.

The writers arrived around five or six o’clock. At times there would be nearly two dozen of them in the room. The better writers were invited nearly every weekday, the lesser ones just once a week. The goal was for each of them to bring in twenty jokes. One by one they would pitch me their best ones. Most of the time it was every joke for itself. Sometimes I asked in advance for material on a particular subject, such as television commercials. Or I’d start a meeting with, “Did you see that on the news? We need to come up with stuff on that.” Mitchell Walters, who was one of the Outlaws of Comedy with Sam Kinison, once said, “Damn man, this place is packed. Pretty soon we’ll be having meetings at Dodger Stadium. You’d hear over the loudspeaker: ‘Anyone with material on the economy report to second base!’”

I had a guideline sheet I gave prospective writers:

AREAS TO AVOID:

ALL MATERIAL MUST BE AS NONETHNIC AS POSSIBLE

1.

NO religious jokes

2.

NO ethnic humor (especially NO black humor)

3.

NO abortion, Kotex, dildo, vibrator, prophylactic jokes, dick jokes

4.

NO

“GOOD TIMES”

jokes

5.

NO ghetto humor

6.

NO bathroom humor

Allan Stephan, another of Kinison’s Outlaws, would pitch jokes that were too dirty or too rough. When he saw the guidelines, he said, “What jokes

does

this guy do?”

Along with telling writers what not to submit, the guideline sheet did list subjects I wanted jokes for: the economy, women’s rights, family, parents, kids, doctors, lawyers, mechanics, dating, marriage, divorce, school, television shows and commercials, smoking, driving a car, diets and exercise, the post office, white-collar crime, and more.

We did not take a poll or a vote on each joke, but there would be a general reaction. If it was positive and I liked it too, I told Mister Geno to write down the joke in his notebook. If there was a lot of grunting and “That sucks!” or I said “No way,” the joke was tossed and we moved on. But any critic had to be a little careful—their joke might be next on the firing line. Later, Mister Geno typed up a run-down of the finalists, and at the beginning of the next meeting he passed those sheets around. Often it would be Leno who would say, “Know what might make that work” and offer a fix on jokes that needed improvement.

That room was like the Roman Coliseum of Comedy, except everyone sat on leather couches and the only blood was from egos being stabbed. The writers were incredibly competitive. Their self-esteem was on the line and so too was money. Although I paid many of them on a weekly basis, others would get paid only if I bought a joke, usually for $25. They could be vicious with each other, much like when we hung out at the Camelot in New York or, now in LA, at the Jewish restaurant Canter’s or Theodore’s coffeehouse.

They would even go after me, the guy writing their checks! Jeff Stein, who partnered with Frank Dungan for what I referred to as Frank’n’ Stein the Monster Comedy Writing Team, would gripe to me when I turned down one of his jokes: “You don’t like that joke because you’re not funny! That’s why you’re not getting the laughs you think you should get.”

You had to have a thick skin to absorb all the hits. It also helped to be vocal and forceful to push your jokes ahead, to fight for them to get noticed and appreciated. But slugging it out like that was not part of Letterman’s self-effacing personality.

I first saw him at the Store not long after he drove out from Indianapolis in 1975 in his red truck and sporting a bushy reddish beard. I thought he had some good quirky ideas but also felt that he probably was not going to be a tremendous stand-up. He was too uncomfortable on stage in the stand-up format. Maybe, I thought, he could be a host of a talk show or game show. George Miller, who roomed with Dave and was another comic I had become friends with, vouched for him, saying, “I think this guy is funny.” When I asked Dave to join our writers’ meetings, he was very happy. Our sessions were becoming legendary, and he admired many of those in the room—none more than Leno. He was thrilled just to be around those guys.

His wife, Michelle, came with him to LA, but she eventually returned home. When he told me they had split, I said he should get a divorce rather than leave the relationship unresolved.

“You never know what could happen,” I warned him as he sat in my townhouse. He looked at me innocently and asked, “What could happen?” I had my lawyer, Jerry, explain to him what he could lose if suddenly he hit in Hollywood. Jerry then helped Dave get his own lawyer and the resulting divorce was without hostility.

I put him on salary at $150 a week even though he thought he was ill equipped to write for a black comic. He has been quoted as saying, “[Jimmie] wanted me to write jokes with a black point of view. He was the first black person I had ever seen.” That was an exaggeration. In truth he didn’t have any problem coming up with “black jokes,” as shown by these he brought to our meetings:

Birth control is one of the big problems in the ghetto. When I was a kid going out with girls, they would always say, “If you try to make love to me, are you going to use contraception?” I was never sure what that meant, so I’d say, “Hell, I’ll use hypnotism if I have to.”

(December 14, 1975)

You see where police broke up a homosexual slave ring? We had homosexuals back in the old plantation days too. You could always spot the gay slaves. They were the ones picking daisies.

(March 19, 1976)

I used to be real interested in camping. I’d find out when ya’ll were away on a camping trip, then I’d come over and do a little shopping.

(April 12, 1976)

Among his nonethnic submissions was a doctor joke you could almost hear Rodney Dangerfield do:

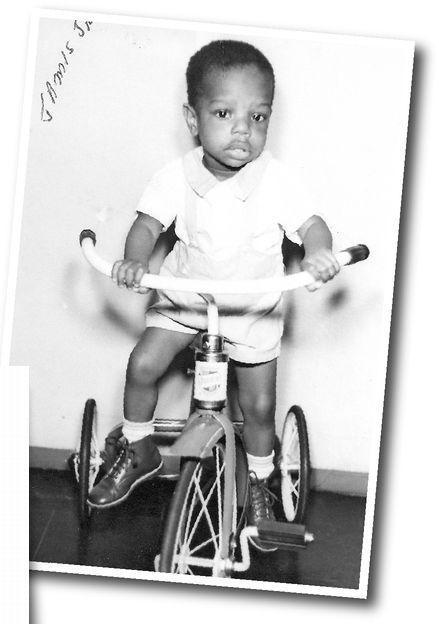

On my tricycle at eighteen months old, probably for the last time because I never learned to ride a bike!

Courtesy Jimmie Walker

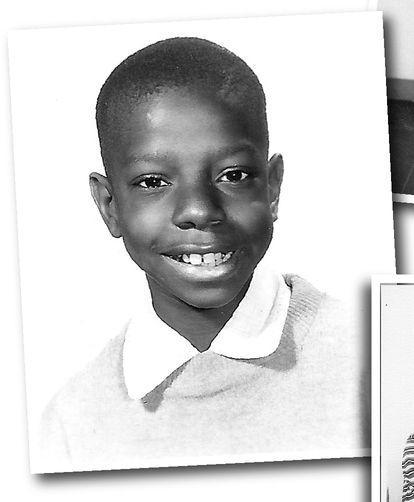

A typical class photo. No inkling of a road comic in the making.

Courtesy Jimmie Walker