Dream boogie: the triumph of Sam Cooke (97 page)

Read Dream boogie: the triumph of Sam Cooke Online

Authors: Peter Guralnick

Tags: #African American sound recording executives and producers, #Soul musicians - United States, #Soul & R 'n B, #Composers & Musicians, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #BIO004000, #United States, #Music, #Soul musicians, #Cooke; Sam, #Biography & Autobiography, #Genres & Styles, #Cultural Heritage, #Biography

Sam was clearly delighted with the song’s evolution, but Bobby felt sick about it, and his brothers weren’t about to let him forget his turncoat role. “You always talking about Sam, he can’t do no wrong with you,” they said, and all Bobby could think to offer in response was that since Sam hadn’t used any of their lyrics, just a groove that could have fit into any song, you couldn’t really call it stealing. But that just inflamed them all the more. “Yeah, he’s got your ticket, Bob,” Cecil, the youngest brother, said sarcastically, and Bobby didn’t even bother to reply. There was no point in arguing. Maybe Sam and Alex really would turn the Valentinos’ next record, “It’s All Over Now,” into a big pop hit. But then, almost before he knew it, Bobby was caught up in rehearsals for the Copa.

They started out in the half studio Sam had crammed into the little house that he used as a retreat back by the carport. Sam had hired a new bass player, Harper Cosby, to replace Chuck, because Chuck wouldn’t fly anymore after a rocky plane ride into New York for an all-star show at the Paramount Theater at the end of March. Otherwise, the nucleus remained the same, with Clif the unquestioned leader, Bobby installed as second guitarist on a permanent basis with the band’s bass slot finally filled, and June flying in from New Orleans for the start of what would soon become five- or six-days-a-week all-day sessions.

There was just about enough room in the little outbuilding for a couple of amps, a drum set, and five people breathing each other’s air. Sam’s attitude was clearly different than at the start of any other tour. They tried one number after another, going over each one until they were locked in so tight they could practically play the song backward. Gradually a repertoire began to emerge. To Clif’s surprise, “When I Fall in Love,” Nat “King” Cole’s 1957 hit, which Sam had originally recorded for his second Keen album, was one of the centerpieces of the set. Clif had first seen it as “a complete one-eighty from [Sam’s] style,” but he had proven that he had a feeling for the song, and now, with that feeling deepened, Clif was finally convinced it wasn’t “a copy of anybody, it [was] strictly an original.”

They worked on familiar showbiz standards like “Bill Bailey” and “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out,” experimented with current folk and country favorites like “All My Trials” and “500 Miles,” and generally woodshedded as Clif guided the band and provided Bobby with firm direction behind Sam’s vocals. “He really knew Sam, and he knew how to keep control of the whole thing. I mean, I could play that cute shit, if Sam hit a note I would hit it right behind him, but Clif held the whole group together so you could have that little cuteness in there. He used to always say, ‘All that little cute-ass shit you playing, just watch me.’ Because I was ad-lib, ad-lib, ad-lib, and he came up from another era.”

The new bass player, whom Bobby dubbed “Hoppergrass” both as a play on his name and because he reminded everybody of a grasshopper with his nervous ways, was working out fine. He played strictly stand-up, but that was Sam’s preference. Nobody got to know him all that well. He never really seemed to relax, and he constantly muttered to himself as he played, but everybody liked the way he spaced his notes, and Sam put an end to all speculation with the pronouncement: “This fucker can play.”

Linda wandered out sometimes to listen to them rehearse. Her daddy would wink at her as he cued the musicians with a snap of his fingers or a shake of his head, and she knew without his ever saying a word how much the Copa meant to him. “It was very, very important. He had in mind how it was gonna go, but he had to make sure it went that way. So he was very, very focused and very, very intense.”

Sam said he was going to get Sammy Davis Jr.’s arranger, Morty Stevens, to write the arrangements for the Copa orchestra. Not René? Bobby asked with some surprise. No, Sam said, Morty had the experience, Morty had

Copa

experience—if Sammy used him, he had to be the best. The only arrangement of René’s that they would keep was “A Change Is Gonna Come,” and Sam doubted they would use that. In fact, he told Bobby, he was planning to include very few of his hit songs—not “Bring It On Home to Me” or “Having a Party” or “Ain’t That Good News” or even “Nothing Can Change This Love.” When Bobby protested that these were the songs that always got the best audience response, Sam gave him a lesson in geography as well as demographics. “He said, ‘I want to be black. I’m not going to desert my people. But to cross over, you must appeal to that market.’ I said, ‘What’s so important about that fucking market?’ He said, ‘Bobby, you listen to the [r&b] radio station. When you turn the corner, that station will go off the air, and you go right to a pop station. That’s how powerful it is. And white people are not gonna come to the black side of town.’” “Twistin’ the Night Away,” with its little cute story, was the kind of song that always went over with white audiences; “Chain Gang” could work in a medley; and “You Send Me” was the one song that everybody remembered. But he was insistent: “You have to be all around, you have to be universal.”

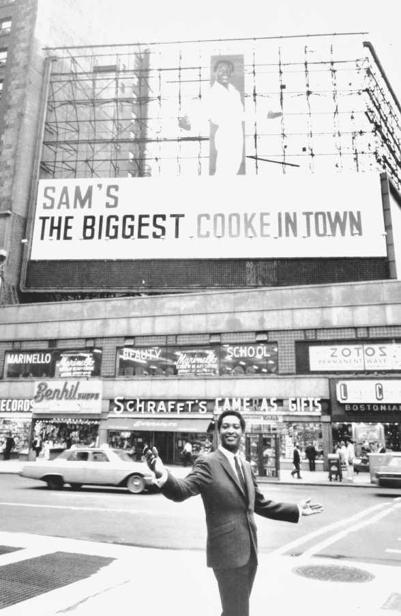

As they got closer to the opening, they moved into a little studio to rehearse, with Gerald Wilson’s band playing Morty Stevens’ arrangements. Nobody liked the new sound. It was loud and brassy, and it felt like there just wasn’t enough room for Sam. None of them said anything, though, because Sam acted so confident, and nobody wanted to disturb his mood. “I’m gonna kill them fuckers,” he said over and over again, and there seemed no reason to disbelieve him. One day he and June were standing out under the carport having a smoke, and he told June about the billboard Allen was putting up in Times Square. “I said, ‘Man you’re bullshitting me.’ He said, ‘I’m going to have my picture right up there on the building.’ I said, ‘Bullshit.’ He said, ‘Wait’ll you fuckers all see.’”

It seemed strange to still be at home when normally he would be out making money, while the weather was good and people had money in their pockets. But he stuck to his rigid daily schedule of rehearsals, and at night he rambled. The Upsetters were at the California Club off and on for close to a month, staying at the Hacienda Motel on Figueroa, out by the airport. The Sims Twins had a regular gig at Bill Goin’s Newly Decorated Sands Cocktail Lounge and Steak House just a few blocks from the motel, and Johnnie Morisette, too, played the Sands on occasion. Sam and former Pilgrim Travelers bass singer George McCurn (“Oopie”) frequently finished an evening of club-hopping out at the Sands before going on to the Hacienda to party with the band. Earl Palmer, the drummer and L.A. session mainstay who had played behind Sam from his first pop session on, viewed Sam’s attraction to the street with increasing concern. He himself had grown up in the New Orleans demimonde, and he knew all the players in the game, but he wasn’t convinced that Sam did. And he was beginning to feel like Sam was drifting more and more toward the kind of people that could do him no good. He didn’t say anything because, for one thing, he didn’t know Sam that well outside the studio. And even if he had, you didn’t ever try to tell Sam anything. Not even J.W. confronted Sam directly, though Earl would have been the first to concede he possessed greater powers of persuasion than most.

Sam was still seeing the girl he had met with Crume; there was never any shortage of girls within the easy radius of his smile, and he continued to relish the excitement that came from being always on the prowl, the sense of anticipation that never failed to kick in at the thought of meeting someone new. Barbara no longer even bothered to hide her contempt. She had acquired a “friend guy” she had begun to see with increasing indiscretion, a bartender at the Flying Fox and a well-known player. She was even brazen enough to invite him out to the house on occasion when Sam was out of town, sitting around the pool with him, kissing and holding hands with the kids right there. It was a nice arrangement, she liked to say, but it was strictly an arrangement. She told her husband she was going out with her sister, just like he told her he was going out with the guys. There was nothing Sam could say to her. He understood what she was doing, but he couldn’t stop her any more than he could stop himself. Everyone looked at him like he was their fucking savior, everywhere he went he was an object of admiration and adoration—and yet he couldn’t muffle the growing discontent, the helplessness he felt at his inability to control not so much the world around him as his private world, the inner world that was revealed to no one but him.

I

T WAS A TIME OF MARRIAGES. J.W.

unexpectedly got married to Carol Ann Crawford, the young woman with whom he had been keeping company for over a year. She had realized she was pregnant only after returning to Hawaii in February, and she and Alex slipped away to Vegas on May 18, a week before her twenty-second birthday, for a quiet ceremony that not even Sam and Barbara attended. They showered the newlyweds with gifts, though, and congratulated Alex on his good fortune—imagine a silver-haired old man who had just celebrated his fiftieth birthday getting such a combination of youth, charm, and beauty—and everyone agreed he had never seemed happier.

Lou Adler married the actress and singer Shelley Fabares three weeks later, in a fancy ceremony at the Bel Air Hotel. Herbie Alpert was there, along with Lou Rawls, Oopie, Alex, recording engineer Bones Howe, and many of their friends going back to the early days at Keen. The bride’s party was dressed in cool mint green, and Sam fronted an all-star group of Johnny Rivers on guitar, Phil Everly on bass, and Jerry Allison, an original member of Buddy Holly’s Crickets, on drums for a brief but memorable guest set.

Sam sold the Maserati and bought a tomato-red Ferrari to replace it. He consistently lost to J.W. in chess and took up archery, while desultorily continuing to pursue Alex’s favorite hobby, tennis. It was golf, though, he told Bobby, that was the key to business success. “Do you know how many deals are made on the golf course?” Sammy Davis Jr. had said to him. So he went out and bought shoes and clubs, a whole golfing outfit, though he never got very far in learning the rudiments of the game.

W

ITH THE COPA OPENING

just three weeks away, Allen finally formalized his arrangement with GAC. He extended the new deal with BMI, too, by which Kags would be credited with 38 percent beyond the prevailing royalty rate from the first dollar. Despite his rapidly expanding business interests in England, his principal focus remained on Sam. RCA had kept up its end of the bargain with a big push on for Sam’s new album,

Ain’t That Good News,

and his latest single release, “Good Times” and “Tennessee Waltz,” which, with close to half a million orders, was easily outpacing the disappointing sales of the last. The twenty-by-one-hundred-foot billboard that Allen had commissioned was scheduled to go up over Schrafft’s, on the corner of Broadway and Forty-third Street, on June 15, posing the teaser, “WHO’S THE BIGGEST COOK IN TOWN?” Three days later, the question would be answered, as Sam flew into the city for a noon press conference to mark the raising of the second stage of the sign: a forty-foot, fifteen-hundred-pound cutout of Sam in five sections, which with its pedestal raised the billboard to a height of seventy feet (“the tallest figure of an entertainment personality ever to be erected in the Times Square area,” read the publicity release) and would be illuminated with “sufficient lamps to produce 20,000 watts, or enough current to keep a household refrigerator operating continuously for four years.” “SAM’S THE BIGGEST COOKE IN TOWN,” read the accompanying message.

Times Square, June 18, 1964.

Courtesy of ABKCO

All of the trades, and most of the dailies, were present to cover the event. “Technical difficulties kept the figure from being raised on . . . schedule,” reported

Record World,

“but that didn’t keep the conference from getting off the ground. Sam took the opportunity to talk about himself, his interests and his plans for the future.” He spoke of his songwriting, SAR’s young artists, and his own ambitions to travel abroad and create a one-man show. “Closing the meeting with a glance out the window to see how the sign painters were progressing, Sam said, ‘I want to be good.’”

He was somewhat less delphic in a late-night meeting with a British reporter at the bar of the Warwick Hotel, where, according to

Melody Maker

correspondent Ray Coleman, he was drinking Bloody Marys and the bartenders all knew him. He was in New York, he said, lighting a menthol-tipped cigarette, “to fix everything up for my two weeks at the Copacabana. . . . I want to envelop another area of entertainment which I haven’t exploited to its fullest capacity.” In his seven years in the business, he had so far appealed primarily to the young, but now that his fans had grown up, he said, he wanted to “mix the old materials with the new—a very careful blend of songs which I’m working on.” He started talking about how he was going to begin introducing “more sophisticated things,” but then, before Coleman knew it, “Sam was talking of the British pop invasion of the States.