Dream boogie: the triumph of Sam Cooke (92 page)

Read Dream boogie: the triumph of Sam Cooke Online

Authors: Peter Guralnick

Tags: #African American sound recording executives and producers, #Soul musicians - United States, #Soul & R 'n B, #Composers & Musicians, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #BIO004000, #United States, #Music, #Soul musicians, #Cooke; Sam, #Biography & Autobiography, #Genres & Styles, #Cultural Heritage, #Biography

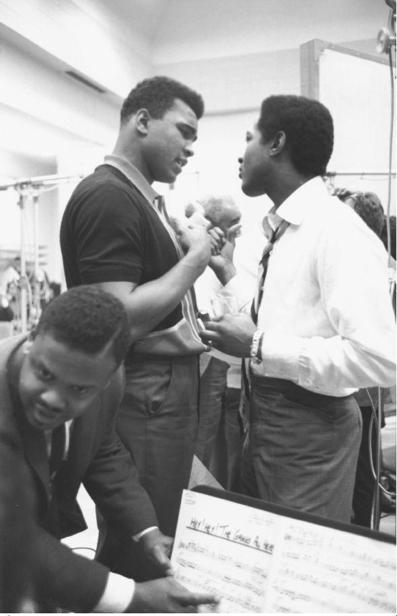

“Hey, Hey, the Gang’s All Here,” March 3, 1964.

Courtesy of Sony Legacy

To Luigi it was business as usual. He and his partner and cousin, Hugo Peretti, were nearing the end of their run at RCA—their contract was about to expire in March, and they were increasingly frustrated by what they considered the label’s refusal to move on their a&r recommendations (“We said to [RCA president] Marek once, ‘You ruin everybody you buy’”). But Sam seemed exactly the same, cheerful, focused, full of ideas. Luigi knew all about the drowning death of the son, but he didn’t say anything about it, and Sam didn’t say anything, either. That was just the way he was. It was Barbara who was the problem. She sat in the back of the control room, sullen and distracted, visibly out of it in a way that no one could miss. Sam seemed to ignore her for the most part. There were moments, Luigi noticed, when he appeared lost in thought, but then he’d come right out of it—he was, as always, in perfect control of himself and his surroundings.

He could, of course, have been thinking of a lot of things. He might have been frustrated at his inability to get “Good Times” just the way he wanted it. Barbara’s presence could well have unsettled him, for all of his studiedly calm demeanor. But mostly he relished the idea of finally being in control—what would make this session different, Allen had told him over and over, was that now he was finally working for himself. He could do whatever he wanted, and contractually he could take any length of time to do it. Which perhaps explained his and René’s slight departure from their usual working methods. At the end of the evening, he was no more discouraged than if he had been working out a song at home: he was simply focused on the two sessions coming up the following evening.

He kicked off the six o’clock session with a number he had begun in the car with Bobby Womack while they were out on tour the previous fall. He still hadn’t fully worked it out and did only one complete take, a kind of glorified demo, with flute, banjo, and marimba supplying a gentle, clippity-clop sound. “When I go to sleep at night,” he sang:

I add up my day

Trying to recall the things I’ve done

And debts I have to pay

For that is one thing

That I know

What you reap is what you sow

And then in a chorus that seemed to reflect almost unintentionally the challenge of applying Old Testament lessons in an existential age, he offered the only hope he could summon up:

Keep movin’ on, keep movin’ on

Life is this way

Keep movin’ on, keep movin’ on

E-v-e-ry day.

The same wistful mood, and same flute obbligato (“That’s another Italian!” Luigi volunteered in response to Sam’s use of the term), were carried over into the next number, “Memory Lane,” the song J.W. had sung to Allen in New Orleans. “One-take Cooke,” Sam called out cheerfully after a few takes, and then he returned to “Good Times,” continuing to experiment with different approaches until he finally got the sound he wanted on the twenty-fifth take.

The ten o’clock session might just as well have been planned for another artist. Against Clif and Alex’s advice, Sam had hired Joe Hooven, the arranger they had used for Mel Carter’s lavishly orchestrated SAR sessions, to write the charts for the four songs he had left to do. From Clif’s point of view, Hooven’s arrangements “just kind of overpowered Sam,” but it was almost as if Sam was insistent on making the point “Look at me. I can do anything. Don’t corner me off.”

He started with “Basin Street Blues,” a number virtually defined by Louis Armstrong, sailing through it with all the confidence of someone who, he once told a disbelieving Bobby Womack, had modeled his vocal style on the gravel-voiced trumpet player. (“Listen to us both,” he had said. “Don’t listen to his voice, listen to his phrasing. It’s like a conversation, it’s real.”) He showed equal confidence in his approach to both “Home,” an Irving Berlin composition made popular by Armstrong and Nat “King” Cole, and “No Second Time,” a melancholy new composition by Clif, then finished off the session with a beautifully articulated, carefully precise, and somewhat stilted recitation of “The Riddle Song,” in which, for all of the pathos of the lyrics, just as little was revealed as in his television performance of the same song two weeks earlier.

But the evening was still not over. It was one o’clock in the morning, and Sam’s voice was getting frayed, but he returned once more to “Good Times,” overdubbing a couple of deliberately unsynchronized harmony parts as a sketch for one final pass at the song. Allen had told him, “Take your time for once. Don’t do another shitty album,” and it had really pissed him off at the time. What the fuck did Allen know about making a record? But with these sessions he had done just what Allen said.

H

E AND BARBARA

threw a small Christmas get-together for their friends. Alex’s girl, Carol, was back from Hawaii, where she had been working on the start-up of a new magazine called

Elegant,

and Sam and Barbara teased Alex that he had better make his move soon. You know, they said, he was nearly fifty, and as cool and hip as he might think he was, not every beautiful, young twenty-one-year-old chick with striking Asiatic features was going to be all that impressed with his gray-haired eminence. He had better just start thinking about the future—before she turned around and went back to the islands to marry some wealthy young businessman. Alex just smiled and kept his own counsel, but Sam could see his partner was smitten, and he took every opportunity to let Carol know that he and Barbara were on her side. It seemed like one of the few things the two of them could still agree upon.

He called Alex right after Christmas and invited him out to the house. He told him that he had a song that he wanted Alex to hear. He didn’t know where it had come from. It was different, he said, from any other song he had ever written.

He played it through once, singing the lyrics softly to his own guitar accompaniment. After a moment’s silence, Alex was about to respond—but before he could, Sam started playing the song again, going through it this time line by line, as if somehow his partner might have missed the point, as if, uncharacteristically, he needed to remind himself of it as well.

It was a song at once both more personal and more political than anything for which Alex might have been prepared, a song that vividly brought to mind a gospel melody but that didn’t come from any spiritual number in particular, one that was suggested both by the civil rights movement and by the circumstances of Sam’s own life—J.W. knew exactly where it came from, but Sam persisted in explaining it nonetheless. It was almost, he said wonderingly, as if it had come to him in a dream. The statement in its title and chorus, “A Change Is Gonna Come” (“It’s been a long time comin’ / But I know / A change gonna come”), was the faith on which it was predicated, but faith was qualified in each successive verse in ways that any black man or woman living in the twentieth century would immediately understand. When he sang, “It’s been too hard living / But I’m afraid to die / I don’t know what’s up there / Beyond the sky,” he was expressing the doubt, he told Alex, that he had begun to feel in the absence of any evidence of justice on earth. “I go to the movies / And I go downtown / Somebody keep telling me / Don’t hang around” was simply his way of describing their life—Memphis, Shreveport, Birmingham—and the lives of all Afro-Americans. “Or, you know,” said J.W., “in the verse where he says, ‘I go to my brother and I say, “Brother, help me, please,”’—you know, he was talking about the establishment—and then he says, ‘That motherfucker winds up knocking me back down on my knees.’

“He was very excited—very excited. And I was, too. I said, ‘We might not make as much money off this as some of the other things, but I think this is one of the best things you’ve written.’ ‘I think my daddy will be proud,’ he said. I said, ‘I think so, Sam.’”

H

E SCARCELY WORKED

the first few weeks of January, just a couple of West Coast dates with Bobby Bland and putting together material for an upcoming Johnnie Morisette session. He was for the most part getting ready for his own follow-up album session at the end of the month. He had a whole new backup band and a whole new approach that he wanted to try.

Harold Battiste, the New Orleans-based multi-instrumentalist who had founded the musicians’ cooperative AFO (All For One), a production company and band that fought for ownership and control of its music, had come out to Los Angeles with his four fellow AFO Executives for the NARA convention in August. They were beginning to think that their idealism might have been misplaced after first losing their one and only hit, Barbara George’s 1962 smash “I Know,” to the rapacity of the music business and then, far from experiencing a wave of fraternal concern from fellow musicians, sensing that they were regarded as interlopers and rivals by both the union and NARA, the association of black radio announcers. With New Orleans a dead end, all five decided to make a new start in Los Angeles after the convention: saxophonist Red Tyler, trumpet player Melvin Lastie, bassist Chuck Badie, and drummer John Boudreaux, along with Battiste, the former teacher, social communard, and lapsed Black Muslim who had helped with the background vocal arrangements on Sam’s “You Send Me” session.

Unfortunately, Los Angeles proved even more daunting than New Orleans in terms of making a living. There was a six-month union residency requirement, they discovered, before you could get steady club work, and they were living pretty much of a hand-to-mouth existence when Harold and Melvin Lastie hit the streets in early fall, looking for any kind of work they could get.

Somehow they found their way to SAR. Sam and Alex were out of town at the time, but Zelda was in the office with Ernie Farrell, the white promo man she had hired to sell Mel Carter’s record, and after hearing them out, she said she could use someone to write lead sheets for their copyright applications. Harold, by his own account, stood there like a dummy, “but Melvin said, ‘My man can write you some lead sheets.’ Talking about me! So that’s what I started out doing, just to generate some income. And by the time we hooked up with Sam, we had a good connection going.”

Sam certainly remembered Harold from the “You Send Me” session, and he knew Red Tyler, too, from his first pop session in New Orleans (Tyler had played sax and written “Forever,” the B-side of the single that had come out under the name of Dale Cook). He hadn’t gotten to know either one of them well at the time, but now he and Harold hit it off like long-lost brothers, as they started talking about race, justice, and other matters far removed from the realm of commercial music.

“It was obvious,” said Harold, “that he wanted to be more than just a popular singer, that he wanted to be involved in social things.” They would go out to the house and talk in the office that Sam kept in the little building out back by the carport, away from Barbara, who didn’t really seem to Battiste to be part of Sam’s evolving world. J.W. was. Battiste, in fact, recognized in Alex a fellow teacher, something like a tribal elder, “a smooth cat who was always trying to teach someone about the music business, or white folks, or something like that.”

Eventually Harold worked up the nerve to approach Sam about something that had always been part of his greater plan, setting up a series of storefront headquarters in the heart of the black community that could serve as both rehearsal space and audition centers for some of the talented but disaffected black youth who would never otherwise find their way to SAR’s offices or, for that matter, anywhere else in Hollywood. He had done the same thing to a limited extent in New Orleans, he explained to Sam. “It was part of my little civic thing, we would let the people come in and audition them and help them prepare their material to take it to the next level.” They could call each of these storefront locations Soul Stations, and they would be useful for SAR’s young artists like the Valentinos to work up material, too. He wasn’t sure at first if Sam was fully tuned in to the idea, but then, to his amazement, Sam just went for it. “Go on and find a place,” he told Harold without hesitation. “I’ll pick up the tab.”

By then Sam had made up his mind to use the band not just on his own upcoming session but as a kind of house band for future SAR projects as well. They would give his music a new sound, a different sound, one that would provide a distinctive mix of sophisticated polyrhythms, jazz voicings (Harold had started out playing with Ornette Coleman, and all of the AFO musicians were modernists to one degree or another), and the kind of melodic simplicity that Sam’s songs had always shared with the New Orleans tradition. It was the idea of music as a collective experience, Harold felt, that excited Sam most, the AFO sound “wasn’t slick, it was sort of raw, [it was] the way that New Orleans people played, and the spirit that happened with that feeling. I hate to seem mysterious, but to me that’s what it is, a spiritual thing, the whole atmosphere that’s created—I think that’s [why] Sam was attracted to us.”