Drama (4 page)

Authors: John Lithgow

One summer during those years, when I was twelve years old, I had the chance to put those lessons to work. The occasion was the big show on the last night of a week of Boy Scout camp, with hundreds of raucous boys in attendance. Our troop had been chosen to put on a skit. We had come up with a ten-minute version of the old melodrama involving a hero, a villain, and a damsel-in-distress tied to the railroad tracks. I must have been either the most accommodating or the most spineless Scout in camp, because I had ended up in the role of the damsel-in-distress.

That afternoon we haphazardly rehearsed for about fifteen minutes, then decided that in the evening we would just wing it. At showtime, I awaited my entrance in the darkness in my improvised costume. I wore a checkered tablecloth for a skirt and a Scout bandana for a headscarf. Combat boots completed the picture. The rustling sound of the crowd filled me with terror. I was a quivering bundle of nerves, anticipating the most mortifying humiliation imaginable. But alas, there was no turning back.

My cue arrived, I made my entrance, and I threw myself into the scene. I must have been emboldened by the memory of all those Shakespearean histrionics back at the festival. Whatever I drew on, it worked. The crowd of boys greeted my every fey line and my every mincing gesture with gales of laughter, hooting their approval. The hero, played by Eagle Scout Larry Fogg, untied me from the tracks, hoisted me into his arms, and fell backwards onto his butt with me on top of him. The laughter was earsplitting. It filled me with joy. Like Bert Lahr, we wore them out.

For a week, I had been a shy, despondent, homesick camper. As of that night, I was a Scout Camp star. If you hear enough applause and laughter at a young enough age, you are doomed to become an actor. After my performance as the damsel-in-distress, my fate was probably sealed.

T

he irony is that I had no intention of being an actor. Oh, I loved the energy and excitement of theater, I adored the Festival’s plays and players, and nothing matched the giddy sensation of actually being onstage. But I never thought of any of this as anything more than a summertime diversion. I had another, altogether different, calling. I wanted to be an artist.

Early on, I felt myself in possession of an innate talent and facility for drawing and painting. In those early years, I would gravely announce to whoever asked (and to many who didn’t) that I was going to be an artist when I grew up. I would lose myself for hours on end with colored pencils, pen and ink, and tempera paint. With my best friend, Eric Rohmann, I would write stories about warring tribes of good and evil elves, an ongoing saga to rival

The Lord of the Rings

. Then I would create elaborate illustrations for them. I even painted watercolors of scenes from the Shakespeare plays and presented them as gifts to my favorite actors.

All of this urgent artistic activity took place before I was ten. Years later, big sister Robin told me that she’d found it all insufferably pretentious. Looking back, I have to agree. But at the time, and for many years later, I was deadly serious.

Who knows where this preadolescent fervor came from? I had not yet had an art class or art teacher to inspire me, I hadn’t had anything resembling an epiphany in an art museum, and, although my parents always made sure that I had the best art supplies in front of me, they did little else to point me in this direction. Perhaps the best clue to the source of these artistic urges can be found in my choice of a role model. At that time, American art was being revolutionized in New York City by the dark energies of Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Willem de Kooning. But growing up in quiet, peaceful, small-town Ohio, I chose to put on a pedestal their polar opposite. My great hero was that archetype of cheerful American normalcy, Norman Rockwell.

Imagine my excitement on the day I actually met the man! In my fifth-grade year, my father took a sabbatical from Antioch to dip his toe back into New York theater. The rest of the family was installed in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, three hours north of the city. Within days of our arrival in Stockbridge, I learned of a breathtaking coincidence. Norman Rockwell’s painting studio was just above the candy store on Main Street, about a hundred yards from our rented house! One day after school I summoned up all my courage and set off to meet the great man. With a Brownie camera in my hand and a prized copy of

Norman Rockwell, Illustrator

under my arm, I marched up the back stairs of the candy store and knocked on Rockwell’s door. The door swung open and there he was. He wore a homely brown sweater and corduroy trousers, and he held a pipe between his teeth. A huge half-finished painting for a

Saturday Evening Post

cover was propped on an easel behind him. A nervous, starstruck eleven-year-old introduced himself, asked for an inscription in his book, and requested a photo. The modest, silver-headed man obliged him.

And so it was that my first breathless brush with celebrity had nothing whatsoever to do with the entertainment business. I had met my idol. “My best wishes to John Lithgow,” the man wrote. “Sincerely, Norman Rockwell.” I was going to be an artist.

S

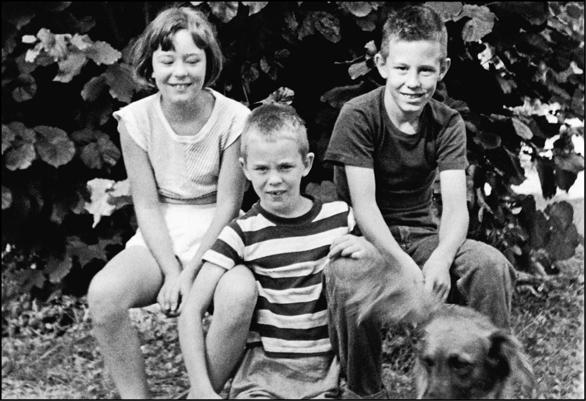

uch boyish certitude characterized everything in my life in those days. Back in Yellow Springs after that sabbatical year in Stockbridge, the family seemed to have nestled into a happy midwestern idyll. Our everyday life resembled a sunny novel written by Booth Tarkington. I was in a different school and a different house, but everything else was comfortably the same. My old gang innocently prowled the leafy streets and backyards of Yellow Springs and the woods of nearby Glen Helen. Eric Rohmann was still my best friend, but now we competed for the attentions of the same girlfriend. My family had reached its quorum when my little sister Sarah Jane was born. She was ten years younger than I, and the focus of adoring attention from the other five Lithgows. We seemed to fit into the 1950s like the figures in a wholesome Norman Rockwell painting.

Photograph by Gerald Hornbein.

In school I was gregarious and popular. My schoolmates must have thought that my precocious aestheticism was pretty exotic, but it stirred admiration, never derision. The two sides of my nature were nicely balanced: a cross between Tom Sawyer and a preteen Aubrey Beardsley. My days and nights at the Shakespeare Festival alternated with trips to Cincinnati to root for the Redlegs. My afternoons of landscape painting in the country were counterbalanced by long innings of Little League baseball at dusk. I collected a hundred different titles of “Classics Illustrated,” but I also spent endless evening hours in the summertime playing marathon games of neighborhood hide-and-seek.

Yellow Springs was a likely setting for this duality. To all appearances it was a typical Ohio village, with its whitewashed town hall, its battle monuments, and its Lions Club lunches. But it was part of an Ohio archipelago of liberal-arts college towns, including Oberlin, Gambier, Granville, Kent, Bowling Green, and Berea. And of all those towns, it had by far the most radical, activist, and iconoclastic history. Antioch College was the wellspring of all this radicalism. In the nineteenth century, Yellow Springs had been a major way station on the Underground Railroad, and Antioch warmly embraced the town’s fervent abolitionist heritage. The “Antioch Program for Interracial Education” predated the Civil Rights Movement by several years, and the progressive citizens of Yellow Springs shared the college’s pride in it. My parents were two of those proud citizens. They regularly hired student babysitters from the program for my siblings and me. Our favorite was a vibrant girl named Coretta. A few years after her babysitting days ended, Coretta would marry a young minister from Georgia named Martin Luther King, Jr.

Because of Antioch’s presence, Yellow Springs teemed with pinko bohemians and tweedy anarchists. These were the early Eisenhower years, the era of Joe McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee. The whole country was seized with anticommunist paranoia. But in Yellow Springs there was a gleeful defiance of the conservative tide sweeping the country. The Lithgow children absorbed the town’s politics by osmosis. Adlai Stevenson was our messiah, Richard Nixon was our bogeyman. Our classmates whose professor fathers had been famously blacklisted walked among us with a special swagger. My parents bought their first television in 1954, just so they could watch the Army-McCarthy Hearings.

Photograph by Axel Bahnsen.

Mom and Dad hardly rated the blacklist. They were staunchly liberal, but far from revolutionary. For them, politics took a backseat to a shared passion for theater. Of the two of them, my father was not the only performer. Early in their marriage, my mother played big roles in productions at the opera house. In later years, she loved to smugly invoke the memory of her Madwoman of Chaillot, her Madame Arcati, and her Green Maiden in

Peer Gynt

, but I have no memory of any of them. A photo from those days shows her as Cecily Cardew in

The Importance of Being Earnest

. With a distinctly Lithgovian pout, she is receiving the attentions of an ardent Algernon Moncrieff (played by an actor named Meredith Dallas, co-director with my father of several of Dad’s Antioch enterprises).

But if Mom was wryly boastful of her brief career onstage, she was equally cocky about her decision to leave acting behind. With a household full of kids, a husband consumed with his theater exploits, and a gang of raucous actors constantly tramping in and out of her home, she took on the role of den mother. Her charges were her own children and the childlike adults that formed my father’s company. If this was a grudging choice, she never showed it. Whatever histrionic urges she had left seemed to be satisfied by wistful evocations of dance recitals when she was a child in Rochester and periodic explosions of the Charleston performed in our living room and at boozy cast parties.

My father’s nature mixed whimsy and furnace-like energy. His enthusiasms shot off in all directions, like an unattended fire hose. He shingled our entire house by himself, he constructed a ten-yard overhead wooden grape arbor in our backyard, he built beautiful maple bedsteads for each of us, he lined the master bedroom with knotty pine boards, he invented extravagant breakfast dishes with names like “bleeding heart omelets” and “eggs

spécialité

”—all of this with the same jaunty optimism with which he created a Shakespeare Festival. Late one night, at a supper party in our home, I remember lying in bed and hearing him downstairs declaiming to his adult guests. Someone had asserted that the first act of

The Tempest

was boring. Dad was passionately performing the entire act, playing all the parts, just to prove the Philistine wrong.

Sometimes his whimsy tipped over into recklessness. A typical example of this occurred a few years later. When my sister Robin was in her late teens, she went through a yoga stage. At the time, we were living in a house with a single bathroom. Large and flooded with light, the room was a beautiful space for practicing yoga. One day, on a visit home from college, Robin was languidly doing her yoga on that bathroom floor when my father knocked on the door. She breezily told him to come in, but he was mortified to think that he was disturbing her privacy, so he apologized through the closed door and went away. She heard nothing more from him.

Later that same day Robin was doing some ironing. The ironing board was set up in a room next to that bathroom. She spread out a shirt, filled the iron with water, steamed the shirt, and began to press it. She noticed a strange smell. She steamed the shirt again. The smell was appalling. Caught between revulsion and hilarity, she realized what had happened. Earlier that day, Dad had peed into a half-filled pitcher of water sitting on the ironing board and had forgotten to empty it. Robin had filled up the iron with that pitcher. She was steaming her shirt with her father’s diluted urine. The whole episode uncannily sums up my dad (somewhat at the expense of his dignity): his sweetness, his courtesy, his ingenuity, his abstraction, and, above all, his soaring sense of humor. He roared with laughter every time he told the story on himself. And he told it often.