DIY Projects for the Self-Sufficient Homeowner: 25 Ways to Build a Self-Reliant Lifestyle (35 page)

Authors: Betsy Matheson

Tags: #Non-Fiction

Being off the grid

means no electric bill, no concerns about rate hikes, and no utility-based power outages.

Solar Electricity

Solar ElectricityResidential PV systems supply electricity directly to a home through solar panels mounted on the roof or elsewhere. These are essentially the same systems that pioneering homeowners installed back in the 1970s, except in those days panels were less efficient and much more expensive—to the tune of over $300 per watt in setup costs compared to around $9 per watt today (and people in many areas can cut that number in half with renewable energy rebates and tax credits).

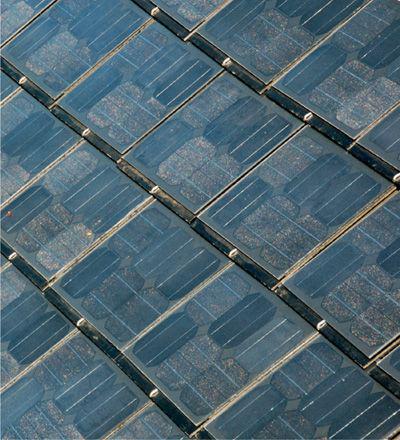

Solar cells:

building blocks for a future of clean energy.

Here’s how PV power works: A solar panel is made up of small solar cells, each containing a thin slice of silicon, the same stuff used widely in the computer industry. Silicon is an abundant natural resource extracted from the earth’s crust. It has semi-conductive properties, so that when light strikes the positive side of the slice, electrons try to move to the negative side. By connecting the two sides with a wire, you create an electrical circuit and a means for harnessing this electrical activity.

Solar cells are grouped together and connected by wires to create a module, or panel. Modules can be installed in a series to create a solar “array.” The size of an array, as well as the quality of the semiconductor material, determines its power output.

The electricity produced by solar cells is DC, or direct current, which is what most batteries produce and what battery-powered devices run on. Most household appliances and light fixtures run on AC, or alternating current, electricity. Therefore, PV systems include an inverter that converts the DC power from the panels to AC power for use in the home. It’s all the same to your appliances, and they run just as well on solar-generated power as on standard utility power.

Grid-Connected & Off-the-Grid Systems

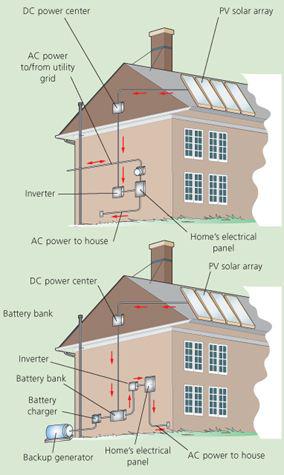

Home PV systems can be designed to connect to the local utility network (the power grid) or to supply the home with all of its electricity without grid support. There are advantages and disadvantages to each configuration.

In a grid-connected setup, the utility system serves as a backup to supply power when household demand exceeds the solar system’s capacity or during the hours when the sun is down. This obviates the need for batteries or a generator for backup and makes grid-connected systems simpler and less expensive than off-the-grid systems. One of the best advantages of grid connection is that when the solar system’s output exceeds the house’s demand, it delivers power back to the grid and you (may) get credit for every watt produced. This is called net-metering and is guaranteed by law in many states; however, not every state requires utility companies to offer it, and not all companies offer the same payback. Some simply let the meter roll backwards, essentially giving you full retail value for the power, while others buy back power at the utility’s standard production price—much less than what they charge consumers.

Grid-connected systems

(top) rely on the utility company for supplemental and backup energy. Off-the-grid systems (bottom) are self-sufficient and must use batteries for energy storage and a generator (usually gas-powered) for backup supply.

The main drawbacks of being tied to the grid are that you may still have to pay service charges for the utility connection even if your net consumption is zero, and you’re still vulnerable to power outages at times when you’re drawing from the grid. But the convenience of grid backup combined with the lower cost and reduced maintenance of grid-tied systems makes them the most popular choice among homeowners in developed areas.

Off-the-grid, or standalone, systems serve as the sole supply of electricity for a home. They include a large enough panel array to meet the average daily demand of the household. During the day, excess power is stored in a bank of batteries for use when the sun is down or when extended cloud cover results in low output. Most standalone systems also have a gas-powered generator as a separate, emergency backup.

For anyone building a new home in an undeveloped area, installing a complete solar system to provide your own power can be less expensive than having the utility company run a line out to the house (beyond a quarter-mile or so, new lines can be very costly). There are some maintenance costs, namely in battery replacement, but it’s possible to save a lot of money in the long run, and never having to pay a single electric bill is deeply satisfying to off-the-grid homeowners.

As mentioned, off-the-grid systems are a little more complicated than grid-tied setups. There are the batteries to care for, and power levels have to be monitored to prevent excessive battery run-down and to know when generator backup is required. To minimize power demands, off-the-grid homes tend to be highly energy-efficient. Using super-efficient appliances and taking smaller steps like connecting electronics to power strips that can be switched off to prevent small but cumulative energy losses from devices running in “standby” mode enables homeowners to get by with smaller, less expensive solar arrays. If you’re interested in taking your home off the grid, talk with as many experts and off-the-grid homeowners as you can. Their experiences can teach you invaluable lessons for successful energy independence.

Solar Panel Products

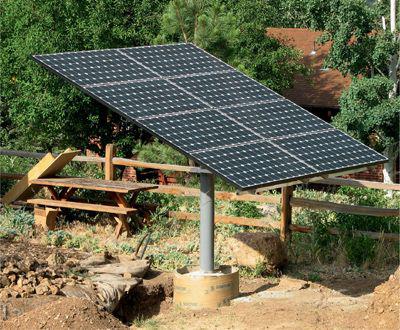

PV modules come in a range of types for different applications and power needs. The workhorse of the group is the glass- or plastic-covered rigid panel that can be mounted to the roof of a house or other structure, on an exterior wall, or on the ground at various distances from the house. Panel arrays can also be mounted onto solar-powered tracking systems that follow the sun for increased productivity.

Mounting solar arrays

on the ground offers greater flexibility in placement when rooftop installation is impractical or prohibited by local building codes or homeowners associations.

Rigid modules, sometimes called framed modules, are designed to withstand all types of weather, including hail, snow, and extreme winds, and manufacturers typically offer warranties of 20 to 25 years. Common module sizes range in width from about 2 ft. to 4 ft. and in length from 2 ft. to 6 ft. Smaller modules may weigh less than 10 pounds, while large panels may be 30 to 50 pounds each.

In addition to variations in size, shape, wattage rating, and other specifications, standard PV modules can be made with two different types of silicon cells. Single crystalline cells contain a higher grade of silicon and offer the best efficiency of sunlight-to-electricity conversion—typically around 10% to 14%. Multicrystalline, or polycrystalline, cells are made with a less exacting and thus cheaper manufacturing process. Solar conversion of these is slightly less than single crystalline, at around 10% to 12%, but warranties on panels may be comparable. All solar cells degrade slowly over time. Standard single crystalline and multicrystalline cells typically lose 0.25% to 0.5% of their conversion efficiency each year.

Amorphous Solar Cells

Another group of solar products are made with amorphous, or thin-film, technology in which noncrystalline silicon is deposited onto substrates, such as glass or stainless steel. Some substrates are flexible, allowing for a range of versatile products, including

self-adhesive strips that can be rolled out and adhered to metal roofing and thin solar modules that install just like traditional roof shingles. Amorphous modules typically offer lower efficiency—around 5% to 7%—and a somewhat faster degradation of 1% or more per year.

Installing solar panels

over an arbor, pergola, or other overhead structure can create a unique architectural element. Here, panels over an arbor provide shade for a patio space while generating electricity for the house.

The Economics of Going Solar

While the environmental benefits of solar electricity are obvious and irrefutable, most people looking into adding a new solar system need to examine the personal financial implications of doing so. PV systems cost only a small fraction of what they did 30 years ago, but they’re still quite expensive. For example, a three-kilowatt system capable of supplying most or all of the electricity for a typical green home can easily cost $30,000 (before rebates and credits) and take 20 to 25 years to pay for itself in reduced energy bills. An off-the-grid system will cost even more. Nevertheless, depending on the many factors at play, going solar can be a sound investment with a potentially high rate of return.

One way to consider solar as an investment is to think of it as paying for a couple of decades’ worth of electricity bills in advance. Thanks to the long warranties offered by manufacturers and the reliability of today’s systems, the costs of maintenance on a system are predictably low. This means that most of your total expense goes toward the initial setup of the system. If you divide the setup cost (after rebates and credits) by the number of kilowatt hours (kWh) the system will produce over its estimated lifetime, you’ll come up with a per-kWh price that you can compare against your current utility rate. Keep in mind that your solar rate, as it were, is locked in, while utility rates are almost certain to rise over the lifetime of your system.