Divine Fury (12 page)

Authors: Darrin M. McMahon

FIGURE 2.3

. Francisco de Zurbarán,

Saint Bonaventure Praying at the Election of the New Pope

, 1628–1629. As higher beings themselves, saints were in proximity to the angels.

Bpk, Berlin / Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden / Elke Estel and Hans-Peter Klut / Art Resource, New York

.

FIGURE 2.4

. Anonymous,

The Dilemma of the Christian Knight

, seventeenth century. The Christian knight who would achieve transcendence must beware, lest he mistake the seductions of Satan for an angel of the Lord.

Private Collection, Madrid, Spain / Album / Art Resource, New York

.

FIGURE 2.5

. Rembrandt Van Rijn,

Faust in His Study

, c. 1652–1653. The legendary Germanic myth of Faust, who sells his soul to the devil in return for occult knowledge, may have been based on an actual German magus of the fifteenth century. The legend was recycled continually thereafter, most notably by Christopher Marlowe and Goethe.

The Victoria and Albert Museum, London / Art Archive at Art Resource, New York

.

FIGURE 2.6

. From Andreas Vesalius’s celebrated anatomical atlas

De humani corporis fabrica

(On the structure of the human body), first published in Basel in 1543. The Latin caption reads “Genius (

ingenium

) lives on, all else is mortal.”

Wellcome Library, London

.

FIGURE 3.1

. Louise Elizabeth Vigée-LeBrun,

The Genius of Fame

, 1789. In art, particularly iconography and painting,

genii

were prevalent in the eighteenth century, even as they were banished from life. Commonly used to depict the governing spirit of a place or an abstract entity, they were most often represented as winged cherubs or angels, a convention that dates to the Renaissance.

Bpk, Berlin / Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Berlin / Joerg P. Anders / Art Resource, New York

.

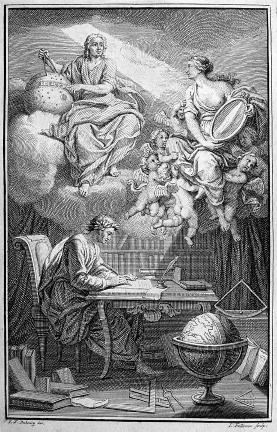

FIGURE 3.2

. The genius (Voltaire) with his

genius

, source of inspiration and light. The frequent coupling of

genii

and men of genius in the eighteenth century perpetuated the conflation of their powers. The Latin epigraph translates loosely as “One day he will be as dear to all, as he now is to his friends.” Engraving by J. Balcchou after a portrait of Jean Michel Liotard, 1756.

Collection of the author

.

FIGURE 3.3

. The prodigy of genius. A nineteenth-century re-creation of Mozart and his sister performing for the Empress Maria Theresa.

Album / Art Resource, New York

.

FIGURE 3.4

. The frontispiece to Voltaire’s

Elémens de la philosophie de Newton

(1738). Newton transmits the divine light of the heavens to Voltaire by way of Madame de Châtelet, the French translator of Newton’s

Principia Mathematica

and Voltaire’s mistress.

Florida State University Libraries, Special Collections and Archives

.

It was for that reason that men and women needed powerful protectors like Gervasius and Protasius, Christian militants who could rout the demons and put them to flight. Ambrose describes them unambiguously as soldiers, but the saints also engaged in combat as exorcists, on the model of their master, Christ. Repeatedly, in the synoptic gospels, Christ commands demons, rebukes them, and drives them out of people and places by the power of the Holy Spirit and the force of the “finger of God” (Luke 11:20). So closely are his miraculous powers linked to the expulsion of demons that he is accused by the Pharisees of being possessed himself. “It is by the prince of demons that he drives out demons,” they charge before the people (Matt. 9:34). The people, nevertheless, are in awe, as are Jesus’s own disciples when they learn that their master’s power is being transferred to them. The “authority to drive out demons” (Mark 3:14–16) is part of Christ’s legacy and gift, bequeathed to the apostles, and then to holy men such as Gervasius and Protasius, men of power who continued the work of Christ. Well into the Middle Ages, the tombs of the martyrs would serve as important sites of exorcism, noisy howling places where, as Augustine gloated, the demons “are tormented, and acknowledge themselves for what they are, and are expelled from the bodies of the men they have possessed.”

11

But if the saints thus exorcised and purged demons—serving as soldiers on the front lines of a great cosmic battle with evil—their triumph was not simply one of brawn. For the same power that allowed them to detect and defeat the many

daimones

of the world provided them with a piercing clarity of vision, the capacity to see through ephemera in order to penetrate to the eternal truths of existence. The soul of the saint was a highly developed instrument that put its possessor in direct contact with the divine. Saints were privy to a higher order of knowledge and understanding: they could relay messages and dispatch wisdom, utter prophesies, petition miracles, and disclose truths with epiphanic power. Privileged to see and hear where others were blind and deaf, saints had access to the deepest verities of existence and so could lay claim to insight and inspiration that no ordinary mortal could attain.

It was in part to honor this aspect of the holy ideal that the church singled out a class of saints renowned for their immense learning and vision, the so-called “doctors” of the church (from the Latin verb

docere

, to teach). Employed somewhat loosely by patristic writers, the title was eventually formalized around the four founding “great doctors,” the church fathers Ambrose, Augustine, Jerome, and Gregory, who were widely recognized as such by the early eighth century. In time, the church added others as well, including celebrated Scholastic philosophers such

as Aquinas, Albertus Magnus, and Bonaventure as well as visionary mystics and seers like Theresa of Avila and Catherine of Siena. Albrecht Dürer’s famous sixteenth-century engraving of Saint Jerome at work in his study—glowing with beatific wisdom and inspiration—attests to the power of the image of the saint as inspired scholar and seer. Jerome’s own fourth-century

De viris illustribus

(

On Illustrious Men

) did the same. The work was a self-conscious attempt to do for Christians what classical authors had done for the “illustrious men of letters among the gentiles,” a direct response to Suetonius and the many other pagan authors who had written panegyrics of philosophers and

viris illustribus

, extolling their wisdom and virtue. Let “they who think the Church has had no philosophers or orators or men of learning,” Jerome challenged, “learn how many and what sort of men founded, built and adorned it, and cease to accuse our faith of such rustic simplicity, and recognize rather their own ignorance.” The good doctor and patron of librarians had a point, and in pressing it home, he and his fellow Christians could appeal with confidence to another source of illumination. For in displacing the guardians and god-men of the ancients, the saints could call on the assistance of their own special protectors to supplement Christ’s

numen

and help carry them to God: every saint had a

genius

of his own.

12