Divine Fury (11 page)

Authors: Darrin M. McMahon

That, it may seem, was an impossible quest, and indeed, Saint Ambrose and his great contemporary and disciple, Saint Augustine, endeavored to show that it was. Augustine devoted his enormous theological energies to proving that human nature had been fatally damaged by original sin and so could never attain perfection unaided—or in this life. Our primal transgression, he reminded his contemporaries, was precisely Adam and Eve’s indulgence in the face of the serpent’s promise, “You will be like God” (Gen. 3:5). Such aspirations were perilous, redolent of hubris and pride. Human beings could never attain transcendence on their own, but only be raised higher by the mystery of God’s freely given grace.

Augustine’s forceful articulation of this point largely succeeded in silencing for a time those who read Jesus’s command to be perfect as if it were possible to fulfill. But it could not dispel the longing or the quest—nor was it, in the end, intended to do so. All who would follow Christ must seek to be Christlike, even if the goal was impossible to fulfill. The

divine example of Jesus was at once a limiting condition and an ideal. And yet, the very effort to take up one’s cross raised a series of nagging questions: If human beings were incapable on their own of overcoming their fallen natures, how might they advance on the road to perfection? Did those destined to be saints possess in their persons an inherent power, implanted or infused by God? To what extent could one cultivate God’s gifts? And how might our own labors and works, the painstaking efforts to be Christlike, contribute to our salvation?

To take up these questions in earnest would be to recount much of the history of Christianity. Theologians have debated the answers for centuries, seeking a definitive solution to the mystery of salvation and grace that not only sundered the Catholic Church at the time of the European Reformation but has generated a range of competing positions ever since. But from the perspective of the history of genius, the salient point is that Christian debates on how human beings might attain transcendence tracked closely with the classical discussion of what it was that made a mere mortal more than a man. What was that special something, this

divinum quiddam

of grace, that made a saint a saint, and how could it be had? Was it present, like superior

ingenium

, from birth? Was it infused by a ministering spirit? Imparted directly by God to those who had earned it through sacrifice and the sweat of their brow? Affirmative answers to all these questions were possible, and they were put forth over the centuries with an explicit awareness of the classical precedents. But regardless of one’s position, it was meant to be clear what the

divinum quiddam

was not. For in the context of the early church there was no escaping a direct confrontation with those mysterious beings who were said by the ancients to have raised human beings to heights that were out of reach for ordinary individuals, and who, in the special case of Socrates’s

daimonion

, were able to endow a man with unsurpassed wisdom and clarity of sight. For Christians, a divine something could not a demon be.

T

HE WORD

DAIMONION

APPEARS

often in the Greek New Testament—fifty-five times, to be exact. And though the preference for the diminutive likely reflects Christian condescension—for all pagan

daimones

were “little” before the towering majesty of Christ—the word could not help but bring the

daimonion

of Socrates to mind, making plain, for those who considered such matters, that Socrates’s vaunted sign was a devil in disguise. The first Latin theologian, Tertullian, points out, for example, that “the philosophers acknowledge there are demons. Socrates himself waited on a demon’s will. And why not?, since it is said that an evil spirit attached itself specially to him even from his childhood—turning his

mind no doubt from what was good.” Tertullian’s contemporary Lactantius, a Christian author and adviser to the emperor Constantine, reminds his readers similarly in the early third century that “Socrates said that there was a demon continually about him, who had become attached to him when a boy, and by whose will and direction his life was guided.” And Saint Augustine, though kindly disposed to Socrates and Plato in many ways, nevertheless sought to emphasize, in an extended discussion of the subject in his

City of God

, that Apuleius’s work was misnamed:

De Deo Socratis

should rightly have been called the

Demon of Socrates

, for that is what possessed him.

9

Tertullian, Lactantius, and Augustine all wrote in Latin, not Greek, and so employed the Latinized

daemon

to describe Socrates’s guiding spirit. None chose a diminutive form to distinguish Socrates’s

daimonion

from other, more general spirits, and that choice was repeated by Saint Jerome when he translated the Bible into Latin. Readers of the Vulgate, as the church’s canonical text is now known, will find

daemon

used for both the Greek

daimon

and

daimonion

throughout. The choice is perfectly defensible in light of the fact that early Christians themselves were sweeping in their understanding and dismissal of the spirits that haunted the mind. The pagan gods, the tutelary

daimones

or

genii

, devils and malignant spirits—all could (and did) fall under the general Christian category of

daemones

, “demons.” What for the ancients had been a neutral term was split off and transformed: in the Christian understanding, all “demons” were evil.

10

That redefinition—or what we might call today “rebranding”—had a curious consequence, preserving at the heart of a nominally monotheistic religion the remnants of a polytheistic conception of the world. Alongside God the Father hovered untold legions of little “gods”—never, to be sure, described by Christians as such—but present nonetheless. No wonder that early Christians saw demons everywhere! The whole of the pagan pantheon—from the Olympians to the most insignificant local

genius

or sprite—was reconceived as the product of mass illusion wrought by the work of conniving spirits. Demons had corrupted souls for centuries before the coming of Christ, and they continued to do so still in a great war for hearts and minds. They lurked about the body and haunted all manner of places, laying traps of temptation, snares of iniquity and sin. Even Jesus is approached by the demons’ dark lord, the master tempter, Satan himself, who after forty days and forty nights dangles before him the “kingdoms of the world” (Matt. 4:8). Jesus resists, but not all are so strong. With legions at his command, the “prince of the demons” can lay siege to the most formidable soul.

FIGURE 1.1

. Peter-Paul Rubens,

Prometheus Bound

, early seventeenth century. The Prometheus myth is an archetype of the dangers, as well as the temptations, of usurping divine creativity and knowledge.

Philadelphia Museum of Art / Art Resource, New York

.

FIGURE 1.2

. William Blake,

Satan Calling Up His Legions

, c. 1805. Inspired by John Milton’s

Paradise Lost

, the painting presents Lucifer, the wisest of the angels, in quasi-heroic terms as a being who dared to rival God.

National Trust Photo Library / Art Resource, New York

.

FIGURE 1.3

. A fresco from first-century Roman Pompeii depicting a guardian

genius

(top center) with trademark cornucopia and offering plate, surrounded by household gods (Lares). Below are two serpents, common representations of the

genius

and

genius loci. Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples, Italy. Copyright © Vanni Archive / Art Resource, New York

.

FIGURE 2.1

. Michelangelo Buonarroti,

The Torment of Saint Anthony

, c. 1487–1488. The earliest known work of “Michael of the Angels,” completed when he was still an adolescent, the painting depicts a great Christian saint in combat with the demons.

Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas / Art Resource, New York

.

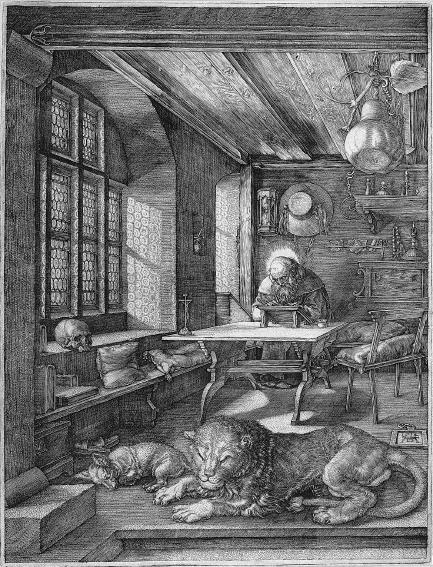

FIGURE 2.2

. Albrecht Dürer,

Saint Jerome in His Study

, 1514. The translator of the Bible as a scholar-saint engrossed in contemplation, privy to special revelations.

Bpk, Berlin / Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen, Berlin / Joerg P. Anders / Art Resource, New York

.