Diamond in the Rough (21 page)

Read Diamond in the Rough Online

Authors: Shawn Colvin

Mario just called me—I’m out of town working on this book. He wouldn’t have bothered me, he said, but something has come up. I’m stricken. Is she all right? Yes, but she now has a boyfriend. (She is twelve.) It’s the second day of their relationship, and there’s a problem. Some of the other girls have told her he’s a jerk, and she told him what they said. Now he won’t return her texts. “It’s the worst day of her life,” Mario says. “I thought you should know.” He says they sat and talked about it for a long time, that he told her it didn’t matter what other people said, that it was between the two of them. “But,” he told her, “I may not be the best person to talk to about this, because, after all, I am a boy. You should call your mother.” But she didn’t call me. She got herself a boyfriend, and drama ensued within two days (the fruit does not fall far from the tree), but she didn’t need to call me. She had her daddy.

Her first food was whipped cream. She walked at ten months; she never crawled. She laughed out loud in her sleep when she was less than two weeks old. They say it’s not possible for them to laugh at that age, but she did. When I asked someone about it, I was told, “She was chasing angels.” I believe it. She never slept through the night, ever. Not even to this day, I don’t think. She talks faster than she can think, and her chatter is punctuated by great, deep gasps in an effort to keep the flow going. It’s a sort of irritation to her to have to breathe if she’s speaking. When she was four, she announced to me while in the bath one day, “I am in love with my clitoris.” After I reprimanded her for farting loudly in a Chinese restaurant, she shot me down by glancing around and saying with a shrug, “It’s okay. They speak Chinese.” I can only assume she farts in English. At the most unexpected times, she will bury her face in my neck and say, “My mama,” and I am always, always amazed by this. Someone calls me “Mama.” Indeed, I became someone else.

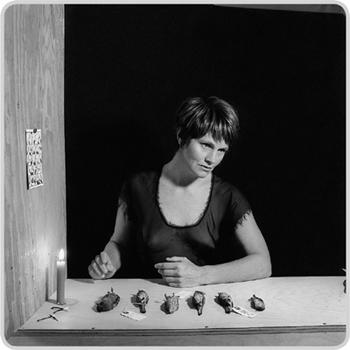

Caledonia, 2002

(Photograph courtesy of Kristina Minor)

Little did I know that the real test for me was going to be writing songs with this new identity and everything that came with it. I’d just had my first hit record, and I followed it up with a baby. Not a smart career move, but I never did care about that. Still, I was aware during the first year of Callie’s life that I had to make a follow-up record to

A Few Small Repairs

and that there would be an expectation of making another one that would do well. When we made

AFSR,

we didn’t know that it would sell. We just made the best record we were capable of, and that’s still all I know how to do. I would lie awake with her, nursing her, putting her to sleep, and think,

What in the hell am I going to write about?

Lyle Lovett said to me once, “Shawn, if you ever decide to have a kid, don’t write a fucking song about it.” With apologies to my dear friend Lyle, how could I not? She was this wonderful, terrifying, adorable, maddening, thrilling, and crazy bomb detonated in the middle of my life and my career. I wanted to write about the baby—she was my whole life—but it seemed as if every ounce of good creative energy I had was invested in parenting her. I could not find any poetry for it. Words failed me.

I traveled to New York to work with John. Mario and Callie joined me. That was a nice balance; it was great to have my child there so I didn’t have to miss her or worry about her, and I could do my work as well. Things came together. I was no longer depressed. I was no longer looking for the escape hatch. But writing for that album was still torturous. I was stuck. And it was made worse by the fact that

A Few Small Repairs

had been so free and seamless and effortless. I thought we had cracked the code. Ha.

What finally happened was, I gave myself permission to express the fear I was feeling. That was the taboo part, and it was keeping me stuck. During that first year, I had such an urge to run away. It’s in my personality. I don’t like being made to do anything. But it’s so wrong to want to run away from your baby—how could I say that? Years before, I had started some lyrics as a love song: “I can pack myself up in a matter of minutes / And leave you all far behind, / All of my old world and all the things in it are hard to find … / If they ever were mine.” I returned to them, and that worked. I could sing about wanting to run but not being able to, chastising myself for having to grow up under the gun, finally. That was the song “Matter of Minutes.”

The record is called

Whole New You,

almost called

Bonefields,

but we thought that was too dark. It’s a strange, confused, moving piece of work. It was never promoted, and it never sold, and I largely ignore it in my live performances, which is a shame, because there are special songs there. Some, like “One Small Year,” I can’t even play, because John does it on piano. That one has a line about not knowing my own face, and I meant it literally. “Nothing Like You” is a love song to Callie. So is “I’ll Say I’m Sorry Now.” “Bound to You” is about the bond between us, “Mr. Levon” about the depression. I’ve always liked the reference that there is light at times when you are in that state but it’s abstract and disoriented, “like California under glass.” That’s always the way I felt in California, like I was under a glass dome. “Another Plane Went Down” is an eerie journal about the fragility of life.

Alternate cover for

Whole New You,

2001

(Artwork courtesy of Julie Speed, with photograph courtesy of Kate Breakey)

Whole New You

was released on March 27, 2001. It tanked. What a difference four years made. Nobody bought it; hardly anybody heard it. The climate of hit radio had changed completely, and the abundant promo opportunities offered before by Columbia were close to nonexistent. It had been too long—five years—since the previous hit record, and the people at Columbia felt that the material was not going to be radio worthy.

Labels are run less and less these days by music fans and more and more by businesspeople, and the concept of building an artist slowly so he or she will have staying power is being abandoned for signing manufactured acts that can have big hits right out of the chute. There’s no room in it for someone like me. I am not your big-hit artist, although I did have a big hit. The climate had changed; it wasn’t about women singer-songwriters anymore. That had passed.

In many ways I don’t really feel as if I’m in the music business anymore. What I do is kind of archaic. I don’t belong at a label that’s going to want a million-selling record. That’s just not me, and aside from one song and one record, it never really was. I go and play shows with a voice and a guitar, and people come to see me because that is what they want to hear.

Of course, there are great opportunities now that you can have a studio on your iPhone and basically anybody can make a record and put it on the Internet. I think it’s pretty cool when I see a commercial and there’s this strange song that they just plucked from somewhere and some unknown person gets this big boost. But there is a downside, too. Everything just seems so disposable. I feel I really don’t know what’s out there. I listen to old stuff. I’m not in touch with what’s vital except through Callie sometimes.

With

Whole New You,

my manager met with the president of the label who told him flat-out, “There’s nothing I can do with this record.” But my manager didn’t tell me this until later. I was the last to know. I just slowly figured it out. It was a very bitter pill. Over the course of the next year, I fired my manager, left Columbia, bought a new house, and got divorced. Again.

The Manhattan skyline, a bed and a byline.

I’ve come and I’ve cradled your face.

And I won’t be the last one to commit crimes of passion

With a shoot-out and a chase.

I’m deeply ashamed to have been divorced twice, but not as deeply glad as I am to be divorced. I have a commitment problem and some pesky trust issues that just don’t jibe with boy-girl intimacy. It’s something I’m learning about myself—I am a loyal friend, a dedicated mother, a dependable colleague, a loving sister and daughter, but I am a lousy girlfriend and an even worse wife.

Here is a list of the men I have found attractive: men who don’t want to be with me, men who do want to be with me but can’t commit, men who want to be with me but have some fatal flaw, men I don’t know, men I know but who refuse to give up fantasies of changing. I seem to yo-yo between blonds and brunettes. If my former boyfriend/husband was blond, then the brunettes have a better shot, and vice versa. Oh, and gray and balding are now copacetic, too. For instance, my last boyfriend was blond and big. My current interest is graying and skinny. I think it’s a form of retaliation, of not giving the last one the satisfaction of even thinking I’m trying to replace him. Of course, it’s all one big mess of penis envy and Electra complexes, but let’s table that for now. I also believe I attempt to shore myself up in the “this one will be different” department by changing the scenery, if you know what I mean. But it’s useless, mainly because

I’m

always in the equation, the one constant. There doesn’t seem to be any way around that.

As I said to Stokes once, “Why can’t I find a man with more than potential?”

You see, at the beginning I want to believe, as all of us do, so much so that I ignore huge red flags. I’ve discounted sexual addiction, alcoholism, financial improprieties, still being married, homosexuality, toxic narcissism, compulsive lying, and more often than not just your garden-variety bad-boy-dyed-in-the-wool hounddoggishness. Everybody has something, I rationalize.

My song “The Facts About Jimmy” I wrote for someone I never actually dated but was entirely, madly in love with. I believe I’d met him twice, and he jerked my chain a couple of times. He was an absolute dreamboat. He invited me to dinner, and I couldn’t believe he might even be interested in me. But ultimately the most that ever happened was that he touched my foot in a hotel room, which I thought was a good start, but there was no follow-up, and I was somewhat bitter. At the time “The Macarena” was at the height of its popularity. You couldn’t go anywhere without hearing that song and seeing the accompanying video of two aging Brazilians and their moronic dance. As is the case with all gigantic dance hits, however insipid, once they’re in your aural atmosphere, you cannot get rid of them.

One night I was visiting Stokes, and he insisted we watch a pay-per-view video channel and purchase the Macarena—he had succumbed. Stokes is my go-to guy for a man’s perspective; he gives it to me straight. After hearing the paltry details of my Jimmy situation, he paused and said, “I don’t know why, but for whatever reason he doesn’t want to fuck you.” Right then and there, I knew what I had to do. I called Jimmy—I didn’t know about caller ID yet—and left “The Macarena” on his voice mail so he would be infected with it. Like getting an STD without the sex.

I guess one of my most creative acts of revenge occurred with my second husband, Mario. Callie was itty-bitty brand-new, and I was deep into breast-feeding her.

She

was deep into colic. I tried to keep a record of when she nursed, but it read like Kafka, and I resigned myself to just popping out the breast anytime she yelled, which was constantly. I learned to pump a small village’s worth of milk after each feeding so we could freeze it and Mario could handle some of the legwork. One day she just wouldn’t eat. I’d give her the breast, and she would latch on and then shake her head like a pit bull. When Mario offered to try the bottle, I was offended. If she didn’t want it from the source, why would she want the bottle? He reasoned that he made the bottle milk hot.

“It’s coming out of me at ninety-eight point six degrees, for Christ’s sake!” I shouted.

“I think I make it a little warmer than that,” he countered demurely.

Well, that was it. Knock my mothering any way you want, but don’t tell me that my damn breasts are not doing their job. The next morning I took some of the steaming breast milk he had warmed for a feeding, sweetly offered him a cup of coffee, turned my back, and fixed it with breast milk. He never knew the difference.