Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China (129 page)

Read Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China Online

Authors: Ezra F. Vogel

By contrast, Jiang Zemin's subordinates who later became the leaders of the fourth generation were not revolutionary heroes, but rather good students who had grown up in the system established by Deng and the others of his generation. They had been born during the war years, but they received their schooling after 1949 under the Communist leadership. They came of age too late to have had the opportunity to study in the Soviet Union or Eastern Europe but too early to have pursued advanced education in the West. Yet even though they were in school before subjects like Western law, economics, and business administration were introduced, they began learning

these subjects after coming to office, through documents, meetings, and short-term training courses. They were able, broad-gauged technocrats, mostly trained in engineering, who accepted the system and wanted to make it work. As a group, they were noted for being responsible, for enjoying good relations with their peers and subordinates, and for not challenging their superiors. They had not been tested in grave crises and they were not prepared to challenge the system. Instead they worked pragmatically and competently within the framework that Deng and his generation had built.

The Fruits of the Southern Journey

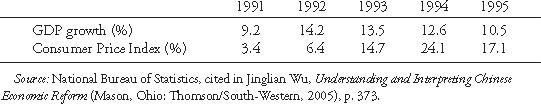

In line with the policies laid down at the 14th Party Congress and the NPC meeting of March 1993 that supported growth targets of 8 or 9 percent, more local investment and construction was permitted. In the several years after Deng's 1992 southern journey, China achieved some of the fastest growth rates the world has known, on a scale never seen before. Indeed, from 1992 to 1999 China, with the world's largest population, grew more than 10 percent per year.

Following the Tiananmen tragedy, from 1989 to 1991 foreign direct investment in China stagnated at $4 billion per year; from 1992 to 1999, however, with China's policy of opening to the West and the gradual easing of foreign sanctions, it averaged more than $35 billion per year. The rapid growth led to a new round of overheating and inflationary pressures, but by 1995 Zhu Rongji was able to bring these pressures down with a soft landing.

A decision to grant selected companies the right to interact directly with foreign companies was a great boon to the expansion of foreign trade. Before then, exporters and importers had to buy and sell through state trading firms, making it difficult for them to adapt quickly to opportunities in foreign markets. Furthermore, the state trading firms could not manage the rapid expansion of foreign trade. Gradually, however, designated Chinese firms were allowed to deal directly with foreign companies, and the number of designated

firms grew. Housing construction also took off with new initiatives introduced by the reformers. Before 1995, housing was assigned by work units or by city officials. After 1995, as the government opened the housing market, families of state employees were allowed to purchase their homes at subsidized prices. With the creation of a private real estate market and opportunities for profit from the building of homes, new homes were built at a dizzying pace.

73

Deng's southern journey did not silence cautious planners and conservative ideologues, but it again moved the goalposts for what was considered possible; even the most easily alarmed planners gradually began accepting, however grudgingly, a larger role for markets and foreign trade. With so many people benefiting from markets at home and abroad, the policies of reform and opening became irreversible. There was no way China could close the doors it had opened after 1978.

Remembering Deng

In the last decades of the twentieth century, the continuing revolution in China consumed many of its heroes. Deng himself had three ups and three downs, but in his last years, he was more fortunate than any of his fellow leaders, many of whom had met sad and even tragic ends. After April 5, 1976, Mao was faced with the reality that the masses in Beijing had rejected his Cultural Revolution and class struggle and preferred Zhou Enlai's four modernizations. Zhou Enlai died knowing that he was still being criticized by Chairman Mao and by the party to which he had dedicated his life. Liu Shaoqi died under house arrest, the target of criticism, without receiving adequate medical treatment. Hu Yaobang, after being heartlessly dismissed from office, was rejected by his fellow leaders during the remaining two years of his life. Zhao Ziyang died under house arrest, officially shunned and permitted to meet only a few selected visitors. Hua Guofeng, when pushed aside, was humiliated. Marshal Ye did retire happily to pleasant familiar surroundings in his native province, but he was no longer completely comfortable with developments in Beijing.

Deng knew that his handling of the 1989 Tiananmen demonstrations would be regarded by many as a permanent blot on his career. In both China and abroad, many felt that in June 1989 he had become overly concerned with maintaining civil order, and that it was unforgivable for him to have allowed the shooting of innocent people on the streets. They believed he had

not done enough to advance the cause of democracy when he had the opportunity. He had not resolved the fundamental problems of corruption and inequality. Deng's defenders, by contrast, admired his courage for boldly taking responsibility to do what was necessary to hold the nation together.

Regardless of their views on the Tiananmen tragedy, however, many admired his determined effort, at age eighty-seven, to embark on the southern journey as a way of ensuring that China stayed on the course of rapid reform and opening. Indeed, Deng lived his last years knowing that his chosen successors were following the policies he had initiated, and that these policies were helping China to advance. He spent these years with his family, honored by his party and nation. He had guided China through a difficult transition from a backward, closed, overly rigid socialist nation to a global power with a modernizing economy. If there is one leader to whom most Chinese people express gratitude for improvements in their daily lives, it is Deng Xiaoping. Did any other leader in the twentieth century do more to improve the lives of so many? Did any other twentieth-century leader have such a large and lasting influence on world history?

Deng said he wanted to be remembered as he really was. He wanted to be well thought of, but he did not want to be celebrated with the grandiosity accorded to Mao Zedong. Unlike Chairman Mao who compared himself with the great emperors, Deng did not consider himself to be a “son of heaven.” He asked only to be remembered as an ordinary earthly being, as a “son of the Chinese people.”

Deng's last public appearance was on New Year's 1994. After that his health deteriorated and he no longer had the strength to take part in meetings. He died on February 19, 1997, shortly after midnight, at age ninety-two, from complications of Parkinson's disease and a lung infection.

74

He had asked that his funeral be simple and frugal. Mao's body had been embalmed and put on display in the specially erected Chairman Mao Memorial Hall, where it was viewed by the public. In contrast, there would be no memorial hall for Deng. On February 25, some ten thousand selected party members assembled at the Great Hall of the People for a memorial service. Jiang Zemin fought back tears as he delivered the eulogy.

75

The service was broadcast on television, and reports on Deng's life dominated the media for the following several days. In line with Deng's wishes, his corneas were donated for eye research, his internal organs donated for medical research, and his body cremated. The box with his cremated remains was draped with the flag of the Chinese Communist Party. On March 2, 1997, his ashes were scattered in the sea.

When Deng stepped aside in 1992 he had fulfilled the mission that had eluded China's leaders for 150 years: he and his colleagues had found a way to enrich the Chinese people and strengthen the country. But in the process of achieving this goal, Deng presided over a fundamental transformation of China itself—the nature of its relation with the outside world, its governance system, and its society. After Deng stepped down, China continued to change rapidly, but the basic structural changes developed under Deng's leadership have already continued for two decades, and with some adaptations, they may extend long into the future. Indeed, the structural changes that took place under Deng's leadership rank among the most basic changes since the Chinese empire took shape during the Han dynasty over two millennia ago.

The transformation that took place in the Deng era was shaped by the highly developed Chinese tradition, by the scale and diversity of Chinese society, by the nature of world institutions at the time, by the openness of the global system to sharing its technology and management skills, by the nature of the Chinese Communist Party, and by the contributions of large numbers of creative and hard-working people. But it occurred at a time of transition, in which the top leader was granted considerable freedom by others to guide the political process and make final decisions. And it was shaped by the role that leader, Deng Xiaoping, personally played. To be sure, the ideas underlying this sea change came from many people, and no one fully anticipated how events would play out. Deng did not start reform and opening; they began under Hua Guofeng before Deng came to power. Nor was Deng the architect with a grand design for the changes that would take place under his rule; there was in fact no clear overall design in place during this era.

Rather, Deng was the general manager who provided overall leadership during the transformation. He helped package the ideas and present them to his team of colleagues and to the public at a pace and in a way they could accept. He provided a steady hand at the top that gave people confidence as they underwent dramatic changes. He played a role in selecting and guiding the team that worked together to create and implement the reforms. He was a problem-solver who tried to devise solutions that would work for the various parties involved both within China and in foreign countries. He helped foster a strong governing structure that could stay in control even as the Chinese people struggled to adapt to the new and rapidly evolving situation on the ground. He played a leading part in guiding the process of setting priorities and creating strategies to realize the most important goals. He explained the policies to the public in a straightforward way by describing the overall situation they faced and then what concrete measures were needed to respond. When controversies arose, he played a major role in making the final decisions and managed the process so as to minimize cleavages that would tear the country apart. He supported the effort to provide incentives and to offer hope based on realistic enough goals that people were not later sorely disappointed. He supported the effort to give enough freedom to specialists—scientists, economists, managers, and intellectuals—so they could do their work, but placed limits on their freedom when he feared that the fragile social order might be undone. And he played a central role in improving relations with other major countries and in forming workable relationships with their leaders. In all of his work, Deng was guided by his deep conviction that employing the world's most modern practices in science and technology, and most effective management techniques, would lead to the greatest progress for China—and that the disruptions that occurred from grafting these practices and techniques onto a Chinese system were manageable and worth it for the Chinese people as a whole.

It is difficult for those in China and abroad who became adults after Deng stepped down to realize the enormity of the problems Deng faced as he began this journey: a country closed to fundamentally new ways of thinking; deep rifts between those who had been attacked during the Cultural Revolution and their attackers; proud military leaders who were resistant to downsizing and budget reductions; public animosity toward imperialists and foreign capitalists; an entrenched, conservative socialist structure in both the countryside and the cities; a reluctance by urban residents to accept over 200 million migrants from the countryside; and dissension as some people continued to live in poverty while others became rich.

But Deng also had enormous advantages as he assumed responsibility for the overall management of China's transformation. He took over a functioning national party and government in a country that Mao had unified. He had many experienced senior officials who shared his view that deep changes were needed. He came to power when there was an open world trading system and other countries were willing to share their capital, technology, and management skills and to welcome China into international institutions.