Democracy of Sound (17 page)

Read Democracy of Sound Online

Authors: Alex Sayf Cummings

Tags: #Music, #Recording & Reproduction, #History, #Social History

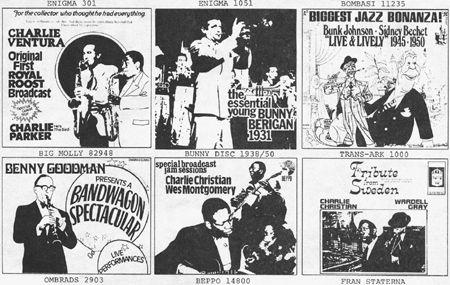

Figure 3.2

This detail from a Boris Rose catalog features mostly live recordings of jazz performers, released on “labels” such as Beppo and Big Molly.

Source:

Reprinted by permission of Elaine Rose.

Boris Rose, for example, offered everything from antique ragtime to comedy records, as well as movie soundtracks, broadcasts of Charlie Parker and Cannonball Adderley, and nostalgia items from the heyday of radio.

75

In this fashion, Rose invented a different label for almost every record he released, starting such companies as Bamboo Industries—Records for Most Jazz Ears, Jung Cat Records, Kasha King, and Lee Bee Discs. He signed the liner notes with pseudonyms like “Kentwood P. Axtor” and “Astyanax Schwartz.” Some of his records, preserved at the Institute of Jazz Studies in Newark, New Jersey, featured homemade Xeroxed covers, while others possessed plain white sleeves much like the

Great White Wonder

bootleg of Bob Dylan that would draw so much attention in 1969. In effect, obscure operators like Rose maintained their own private versions of the government archive that Goodfriend had proposed. Rose was able to maintain such a vast catalog because he only copied discs on demand, when someone sent him a nominal sum ($1.50 or $2.00) to cover the cost of production.

76

“I’m sure he did make money at times because he reinvested it in the music,” Rose’s daughter Elaine recalls. “He never let money really sit in the bank.” She credits his experience of poverty during the Depression for his compulsive desire to collect—stockpile might be a better word—almost anything, from records to exercise bikes to stuffed animals. Rose also possessed the same zeal for documentation that gripped Gould, Goodfriend, and others. With the advent of the video home system (VHS) tape in the 1970s, he filled countless boxes with recordings of television programs. “Because so many people

don’t

save anything, in that era my father was like ‘well, we have to save this—it’s going to be good for history,’” Elaine says. “He was always into preserving things for knowledge. And he was right in that sense. He was afraid that no one would be saving this.”

77

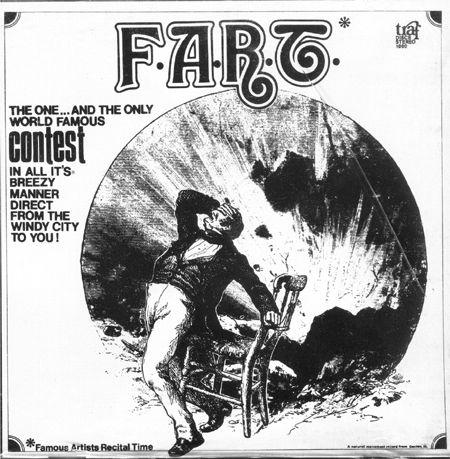

Figure 3.3

A CD compilation of recordings by professional farter Joseph Pujol, also known as Le Pétomane, reveals Boris Rose’s wide ranging taste as well as his penchant for rescuing music from obscurity. On the back of the sleeve, the

London Taxi News

is quoted as asking, “How could anyone seriously dislike an artiste who could blow out a candle from a distance of a foot, or the generation who applauded him?”

Source:

Reprinted by permission of Elaine Rose.

Although Rose and other privateers mostly evaded litigation, the legal status of sound recordings remained in flux throughout the 1950s and into the early 1960s. The 1955 decision in

Capitol Records v. Mercury

forced the Second Circuit

Appeals court to revisit the questions raised earlier by

RCA v. Whiteman

(1940) and

Metropolitan v. Wagner-Nichols

(1950).

78

The convoluted case involved recordings by the German company Telefunken, which had licensed Mercury to sell certain records in Czechoslovakia but gave Capitol the rights to sell in the United States. Capitol wanted to prevent Mercury from issuing the records stateside, while Mercury insisted it was free to sell the records; the recordings were not copyrightable under federal law, and Capitol had given away any possible common law copyright when the works were pressed and sold to the public. (Creators could retain a common law copyright for various kinds of work as long as they were unpublished.) The compositions involved were in the public domain, meaning the question was whether Capitol retained any kind of property right in the recordings themselves.

79

The court struggled with the implications for copyright law, but still came down on the side of Capitol. In his opinion, Judge Edward Dimock determined that sound recordings were not copyrightable, pointing out that congressional committee reports from the Copyright Act of 1909 showed that Congress did not intend “to extend the right of copyright to the mechanical reproductions themselves.”

80

He also observed that

Whiteman

reinforced this principle, but in the next breath said that the 1940 precedent was not, in fact, the law of New York. He instead raised

Metropolitan

as an example, and held that copying and selling someone else’s performances without permission was illegal. Why? Because permitting that behavior “could not have been the intention of the New York courts.”

81

Curiously, the Second Circuit Appeals Court concluded that manufacturing and selling records to the public did not constitute “publication,” allowing Capitol to hold a common law copyright for the works even though Congress and previous courts had chosen not to protect sound recordings.

82

In 1955, it may have seemed that American law had decisively swerved toward granting protection to works that were not technically covered by federal copyright law, but Americans continued to struggle over how much and what kinds of copying were fair. Two Supreme Court rulings in 1964 threw the whole debate into doubt by endorsing the notion that people were free to exploit any works that were eligible neither for copyright nor patent. The cases,

Sears, Roebuck & Co. v

.

Stiffel

and

Compco Corp. v. Day-Brite Lighting

, both dealt with lighting fixtures.

83

Although few would see a direct relationship between a lamp and a sound recording, these decisions directly bore upon how works outside the scope of copyright law ought to be regulated. Lighting designs did not pass the test of originality to qualify for patent, nor did they fall into any of the categories defined in the copyright act, which dealt with books, pictures, musical compositions, and other creative works. Thus, the distinctive grooves on a lighting fixture were no more protected by federal law than the grooves on a particular recording of the song “Hound Dog.” The Supreme Court concluded

in both

Sears

and

Compco

that state rulings in favor of a plaintiff who complained that a competitor copied its fixture design strayed too far into federal territory. If Congress chose not to protect a certain kind of creative object, the court concluded, then lawmakers probably meant to leave it open to free use.

In other words, copyright law by any other name was still the province of federal power. The reasoning derived from a belief in the supremacy of national authority, as well as a bent for leaving as many ideas and expressions in the public domain as possible. The liberal Supreme Court of Earl Warren belonged to an American tradition that distrusted monopolies, as did Learned Hand and Progressive lawmakers in earlier years. Inventing new rights for any kind of creativity, whether the design of a lamp or a musical performance, could be anticompetitive, limiting how others could express themselves and compete in the marketplace.

84

As with the unnamed but numerous freedoms covered by the Ninth Amendment to the Constitution, citizens enjoyed a “federal right to copy” all things not specifically limited.

85

The justices of the Supreme Court affirmed this right just as the Beatles were first invading America and changes in the technology of magnetic recording were about to unleash copying on a much wider scale.

Jets, Cars, and Cassettes

In the 1950s, magnetic tape was a high-dollar hobby and a collector’s craft, as well as a technology that served practical ends in business and industry. In the 1960s it became a vehicle of popular amusement, carried into rock concerts in jean pockets and humming from a Thunderbird dashboard. The high-fidelity enthusiasts were the early adopters of the technology, and their willingness to spend large sums on a prestigious diversion enabled corporations to cultivate magnetic recording as a consumer good, albeit an upmarket one. The medium followed the path of television, which started out as an expensive and bulky product and became ever smaller and cheaper as it evolved.

The invention of a workable transistor in 1947 dovetailed with simultaneous leaps in the development of television and sound recording after World War II. The device was yet another spin-off from wartime research, derived from studies of the conductive properties of silicon and germanium at Bell Telephone Laboratories. Bell scientists discovered that a combination of germanium, plastic, and gold foil could greatly augment an electric current.

86

Engineers replaced large vacuum tubes with tiny transistors that amplified currents enough to power complex electronic devices, allowing the behemoth models of early television sets to shrink and radios to fit into a pocket. Manufacturers could also produce the components in large quantities and achieve immense economies of scale,

reducing the cost of electronic goods. Masaru Ibuka, a founder of the Japanese electronics giant Sony, paid $25,000 for permission to use the transistor when he learned during a visit to the United States in 1952 that Bell was licensing the patent. Three years later, Sony unveiled one of the first low-price “pocket radios,” though the company had to make shirts with extra-large pockets for its salesmen to wear when pushing the product.

87

As Dana Andrews noted, a massive battery of speakers, tape heads, and turntables could overpower the living room of any hi-fi fetishist with money to burn. The pocket radio held out a prospect of cheapness and smallness that could help the consumer who had less space or money make use of magnetic tape technology. In the late 1950s, several companies tried shrinking the tape reel and putting it into a plastic box. RCA Victor developed a four-track tape cartridge in 1958, with little success.

88

In a similar effort to make recorded music more mobile, Chrysler had tried in 1956 and 1960 to install a disc record player under the dashboard of its cars. Understandably, few buyers chose the option, which could be cumbersome and even dangerous to operate on the road. Later innovators sought ways to make tape cartridges easy for a motorist to insert and remove from a player while driving.

89

It was an eccentric car salesman who first initiated the fusion of cars and magnetic tape. Based first in Chicago and later in Glendale, California, Earl “Madman” Muntz managed to make a fortune selling cars during the Depression and the postwar recession by squeezing prices and promoting sales through wild antics. For example, Muntz would advertise a “special of the day”—a car that had to be sold immediately or he would smash it to bits on camera by nighttime. “Muntz is generally credited with starting the ‘this guy’s insane, come take advantage of his crazy prices’ school of salesmanship,” the tape collector Abigail Lavine says.

90

He got into the TV business right after World War II, searching for an angle that would allow him to compete with RCA, Zenith, and the other big companies. He constructed a barebones TV set that would sell cheaply in urban areas; the contraption would not pick up a signal from very far away, but Muntz figured that consumers in big cities like New York and Los Angeles would settle for the cheapest TV possible if the broadcasting antenna were nearby. His design philosophy came to be known as “Muntzing,” which meant hacking away any components that were not absolutely necessary for the device to function.

91

Bill Golden, an engineer, recalled that the company’s $99 TV was known in the industry as the “gutless wonder” in the 1950s because it had so few parts.

92