Democracy of Sound (11 page)

Read Democracy of Sound Online

Authors: Alex Sayf Cummings

Tags: #Music, #Recording & Reproduction, #History, #Social History

Justice Hand had earned a reputation as a partisan of free speech and was suspicious of monopolies, which is how he described copyright in the

Whiteman

case. “Copyright in any form, whether statutory or at common-law, is a monopoly,” Hand wrote. “It consists only in the power to prevent others from reproducing the copyrighted work. W.B.O. Broadcasting Corporation has never invaded any such right of Whiteman; they have never copied his performances at all; they have merely used those copies which he and the RCA Manufacturing Company, Inc., made and distributed.”

63

In a popular speech he delivered at a Central Park rally in 1944, Hand suggested that “liberty is the spirit that is not too sure that it is right,” and copyright is one such issue where he was reluctant to afford too much certainty to the claims of those who produce and own intellectual works.

64

Other courts, however, continued to encounter difficulty in marking out exactly the “more or less” of state protection. Some affirmed Hand’s skepticism about rights to intellectual property while others aimed to protect creators from “offensive” business practices. In the latter group,

Metropolitan Opera v. Wagner-Nichols

(1950) broke with

Whiteman

by ruling that courts should prohibit commercial behavior that seemed plainly unfair to prevailing sensibilities.

65

The New York Supreme Court appealed to a “broader principle that property rights of commercial value are to be and will be protected from any form of commercial immorality.”

66

Again, broadcasting provided the occasion for a dispute. The defendants’ bad behavior consisted of recording and selling copies of radio broadcasts by the Metropolitan Opera, when that organization had already signed a contract with Columbia Records to market recordings of the Met’s music. American Broadcasting joined Columbia and Metropolitan as a plaintiff in the case because the Opera had also signed an exclusive agreement with the broadcaster to transmit the performances over radio. The Met argued that Wagner-Nichols had reduced both the value of its contracts and its ability to secure similar agreements in the future; in this case, the contract issue carried a greater weight than in

Whiteman

. In the earlier case, Judge Hand ruled that although the records carried a label forbidding any use other than home listening, this restriction did not bind the purchaser to abide by it. Wagner-Nichols, however, had interfered in the contractual arrangements between the Met and those who distributed its works, and these agreements had a clear monetary value to the Opera. The defendants also took advantage of the Metropolitan Opera’s sixty years of

“extremely expensive” investment in developing a musical outfit with an unparalleled reputation.

67

For the New York Supreme Court, these injuries outweighed claims by the defendant that their conduct did not meet the traditional definition of unfair competition. Defense lawyers argued that Wagner-Nichols did not “palm off” their products, since Wagner-Nichols did not try to deceive the public into believing that their records were identical to any released by Metropolitan or Columbia. Indeed, the particular performances sold by the defendants were not the same ones Columbia recorded and released. Moreover, the defendants pointed out that they did not infringe on any federally recognized property right, since the Met did not claim any rights to the compositions performed and Congress had not extended copyright to performances or recordings of them.

68

The court found these arguments unpersuasive. The fact that Columbia did sell recordings of the Opera meant that people still might mistake Wagner-Nichols’s discs for the products Columbia had legitimately produced. More important, the court considered the activity wrong even if the charge of palming-off was unclear. “With the passage of those simple and halcyon days when the chief business malpractice was ‘palming off’ and with the development of more complex business relationships and, unfortunately, malpractices, many courts, including the courts of this State, extended the doctrine of unfair competition beyond the cases of ‘palming off,’” Justice Greenberg concluded. Even without deceiving the public, a business could unfairly exploit the “commercial advantage” that rightfully belonged to someone else.

69

Greenberg’s argument goes to the root of unfair competition, as well as to the role the doctrine would play in the recording industry. As a matter of common law, the idea of unfair competition grew out of trademark disputes in the nineteenth century, in which one business would sue another for using its name, thus exploiting the “good will” that consumers already felt toward the more established company.

70

For example, imagine that Smitty’s Breadsticks had shown the public over fifteen years that it sells quality breadsticks with a smile, and also spent money on ads to familiarize people with its good name. Another merchant that uses the name Smitty’s to sell breadsticks would unfairly benefit from the positive feelings that the original Smitty had earned (or acquired, through advertising) for his own business. A pirate could impinge upon and even adversely affect the reputation that a recording artist had developed over time, whether or not the pirate explicitly tried to “palm off” its product as identical to any item released by the artist. In this sense, rulings on piracy protected the right of an artist or company to benefit from the good will they had generated among the public—and this notion of good will could easily apply to the popularity enjoyed by a heavily promoted recording artist, in the sense that the pirate would unfairly exploit the time and energy invested in making a recording popular.

71

Like

INS

and

Fonotipia

, the

Metropolitan

case dealt with the difficulties of regulating the production of cultural goods—whether a newspaper or an opera recording—as industries grew increasingly complex. The dispute in

Metropolitan

entangled musicians, lawyers, radio stations, and record labels in a web of contracts that held value for all involved, as the products and services some offered potentially conflicted with those of others. The question was not so simple as a composer or novelist creating a work and publishing it. Various phases of performing, broadcasting, recording, and retailing were involved in the business of classical music. “The courts have thus recognized that in the complex pattern of modern business relationships, persons in theoretically noncompetitive fields may, by unethical business practices, inflict as severe and reprehensible injuries upon others as can direct competitors,” the ruling said.

72

In this complicated case, the finer details of palming off and property rights did not matter where business practices had a distinct whiff of unfairness. The New York Supreme Court’s ruling in

Metropolitan

is reminiscent of Justice Potter Stewart’s oft-quoted comment on pornography: it may be hard to define what unfair competition is, but a court will know it when it sees it.

73

The Surge of Bootlegging after World War II

“Now there is a babel of labels,” Frederic Ramsey Jr. wrote in the popular periodical

Saturday Review

in 1950. A wave of new entrepreneurs had succeeded Ramsey and his friends in the Hot Record Society, catering to collectors by reissuing the scarce recordings of early jazz. Labels such as Biltmore, Jazztime, and Jay were based in post-office boxes. A former baker in the Bronx had started turning out copies of jazz classics through a variety of labels, such as Anchor, Blue Ace, and Wax, in order to confuse any labels or lawyers who came sniffing down his trail. So many labels had popped up to meet demand for the old records that some were copying the products of other pirates. Their evasive tactics indicate that, unlike Hot Record Society, these businesses did not operate with the sanction of the record companies that owned the original masters. Still, Ramsey argued that the bootleggers prospered under a policy of benign neglect. One New York pirate showed him a letter from the Copyright Office which stated that recordings were not protected by law. “That means that anyone can dub a recording and sell pressings,” the man insisted. In any case, Ramsey felt that the majors were not paying attention. Why, he asked, did the mainstream music industry let bootleggers have the reissue market? “Ah, it wasn’t worth the trouble to put out that moldy stuff,” one executive told him. “It never sold anyway.”

74

When sales of the moldy oldies got too high, though, the major labels saw an interest in testing their rights in court. “Guys were afraid of the big companies, and the big companies were afraid of each other,” one pirate explained. “But now, they’re getting bolder. They found out there’s sort of a feeling with big record company brass that it’s O.K. for a little fellow to dub and sell if his sales just don’t get too good”—a ceiling of about 1,000 records, in his estimation.

75

Sales did indeed look good in 1950. The successful rollout of the vinyl LP record by Columbia two years earlier offered listeners a more durable medium with a longer potential running time than traditional 78 RPM (revolutions per minute) records, but it also meant that many recordings would not be rereleased in the new format.

76

Pirates stood ready to fill any gap that resulted. The bootleg boom received more sympathetic coverage in the

Saturday Review

than in the jazz journal

Down Beat

, which condemned the copiers as “dirty thieves.” Fellow Hot Record Society alum Wilder Hobson followed up on Ramsey’s piece a year later, observing that “the recording seas are now full of piracy.”

77

By then, the three main companies—Columbia, Decca, and RCA Victor—had begun their own series of reissues to co-opt the collectors’ market.

78

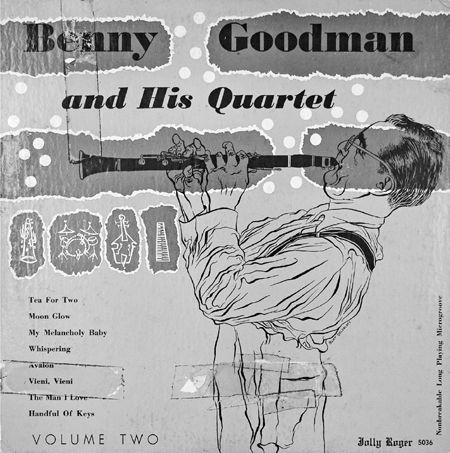

Figure 2.2

A collection of recordings by Benny Goodman repackaged in LP form and released by the Jolly Roger label, circa 1950.

Source

: Courtesy of Music Library and Sound Recordings Archive, Bowling Green State University.

Interest in the origins of jazz had attained new heights by the early 1950s. Alan Lomax’s effort to document folk, blues, and jazz had led to the 1950 publication of the oral history

Mister Jelly Roll

, in which Morton recounted the heterogeneous array of musicians and styles that had developed in fin de siècle New Orleans. (The memoir was also Jelly Roll’s bid for a starring role in the origin story.) Working at the Library of Congress, Lomax had tried to prevent the work of Morton and his contemporaries from vanishing, and others assisted in this task by illicitly copying the recordings. “I am informed that every known commercial record cut can be purchased—if not on original labels, at least as unauthorized reissues,” Lomax wrote. “Jazz, even in its antiquarian phase, operates a bit beyond the pale.”

79

The popularity of

Mister Jelly Roll

, which influenced the later oral histories of Studs Terkel and Theodore Rosengarten, attests to the surging interest in “antiquarian” jazz at this time.

Figure 2.3

This collection of Jelly Roll Morton recordings captures the spare visual flair of many Pax and Jolly Roger recordings, though, unlike Pax records, this Jolly Roger LP featured no liner notes on the back of the jacket.

Source

: Courtesy of Music Library and Sound Recordings Archive, Bowling Green State University.

After World War II, illicit bootleggers jumped into the niche for out-of-print music that the likes of Milt Gabler and the Hot Record Society had opened up. As Ramsey observed, listeners had “for the past fifteen years … been thirsting to hear certain rare records by the great maestros of jazz.” During the war, when supplies of shellac were limited, the music industry could not afford to waste resources on marginal, niche records, making the prospects for historically significant reissues dim. Even when the limitations of war ceased, major labels chose only to resurrect a handful of older recordings as “prestige items,” failing to satisfy the demands of collectors and antiquarians. “It is assumed that such items will both pay their own way and have promotional value for the entire list,” Charles Edward Smith observed in 1952. “The suggestion that the major record companies accept a position of custodianship for recorded hot jazz performances must be regarded as unrealistic. Unless it were presented as something more than a gratuitous notion, it would quite likely meet with tolerant smiles from those who stand to profit more from the exploitation of a current crooner than the rediscovery of a Bessie Smith.”

80

As a result, bootleggers stepped in to meet a demand that had once been met by licensed reproducers like Hot Record Society.