Delphi Complete Works of Jerome K. Jerome (Illustrated) (Series Four) (517 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Jerome K. Jerome (Illustrated) (Series Four) Online

Authors: Jerome K. Jerome

Esther Castways

was produced in 1913. Miss Rowena Jerome made a successful first appearance in this play. During the War she also played the part of Stasia in the

Passing of the Third. Floor Back.

Mr. Jerome said that his daughter and Miss Gertrude Elliott (Lady Forbes-Robertson) were the two best Stasias he had seen.

The Great Gamble

was produced in 1914, just before the War. It had the ill-luck to be a play of German life.

Cook

also was running during the

War, but enemy bombs falling over London suddenly brought it to an end.

The Soul of Nicholas Snyders

was the last play Mr. Jerome wrote. In America it has been used as a Christmas play. It was not written for Yuletide actually, but there is reflected in it the Christmas spirit. It is full of the warm glow of human sympathy and romance, and has in it the conflicting spirits of good and evil.

Before the World War dramatists were moving towards a greater sincerity and a more vigorous manhood in their work. Jerome’s influence was a powerful factor in this movement. But the War put back the hands of the world’s clock. Since the War there has been a glut of sex plays, with their unwholesome and often poisonous atmosphere; and crime plays, with their murders, thefts and horrors, until complaints became general. When Jerome received the freedom of the County Borough of Walsall in 1927, he said:

“I should like to see a stock company here presenting English drama — the best in the world. In London we have little else but American rubbish. The hope of the English theatre is outside London.” Jerome’s life-long advocacy of everything that is sweet and clean in modern plays, and his denunciation of everything that is unworthy, have borne fruit. It has helped the theatre to find its soul. There is at the time of writing a general demand for simple, honest English plays, with less flippancy and more sincerity and real feeling.

CHAPTER VII. JEROME K. JEROME’S HUMOROUS WRITINGS

“Humour is one of the rarest of all literary gifts.”

— ZANGWILL.

“A DOCTOR, not exactly a teetotaller, was consulted by a friend who was also a patient.

“‘I suffer from a constant and unquenchable thirst,’ said the patient. ‘What would you take for it?’

“‘Take for it!’ ejaculated the doctor. ‘Why, my dear chap, in your place I wouldn’t take a hundred thousand pounds.’

“‘I do not happen to have a hundred thousand pounds to spare at the moment; but if I had, and the exchange were possible, I should count the money well spent could I swop it for Mr. Jerome’s happy gift of humour.’”

Thus Mr. Coulson Kernahan begins a chapter on Jerome K. Jerome in his book “Celebrities”.

It is a remarkable fact, though, that Jerome’s humour was not understood by the critics of his early days. It is doubtful whether any contemporary writer met with a more hostile press. He was reproachfully styled “The New Humorist”. One paper was offensive about his “new humour”, and invariably referred to him as “‘Arry K.’Arry”. Others joined in the chorus. He himself has stated that whenever he wrote, “New Humorist” was shouted after him.

The critics apparently did not realize that humour to be worth anything

must

be new. This is as essential as for the breakfast-egg to be fresh. Old humour is rather on a par with the stale

e

gg.

Yes, it certainly was new, and it appealed to a very wide public because it had a new atmosphere of good-fellowship in it. It was the kind of humour they could live with. It was very different from the humour that old-time jesters employed in royal and noble houses; or from the humour, say, of the early eighteenth century; the strongest feature of which was often scurrility, inasmuch as it attacked men’s reputations. It was often offensive and revolting in its vulgarity, and would jest at sacred things.

Jerome’s “new humour” never offends. Its aim is to mix sunshine with the stuff life is made of. It provokes laughter that has some relation to intelligence. Charles Kingsley once stated his belief that the Almighty has a sense of humour, and that He wishes to give happiness to humanity by causing laughter.

For a man to be a humorist he must have that creative gift which is the characteristic of genius. Someone has said that “genius is sent into the world, not to obey laws, but to give them”. The difference between talent and genius is, talent is merely imitative, while genius is creative. Jerome’s genius in creating a “new humour” was recognized by the great mass of readers; while the charity, tenderness, and purity permeating his writings made him one of the most popular authors of his time.

Jerome wrote twenty books, but it would be difficult to classify them into humorous and serious because there is much that is intensely serious and wise in his most humorous books, and much humour in those most serious.

“Idle Thoughts of an Idle Fellow” was written in 1889, while still a clerk and in lodgings with George Wingrave. It contains a blend of anecdote and philosophizing. There is something for every mood in which the mind seeks relaxation. There is profound pathos, which brings tears to the eyes; the next moment there is irresistible humour which brings tears of laughter; and, as Jerome says in this book, “tears are as sweet as laughter to some natures”.

He dedicated the book as follows:

To the Friend Who never tells me of my faults; Never wants to borrow money;

And never talks about himself —

To the Companion of my idle hours,

The soother of my sorrows;

The Confidant of my joys and hopes —

My oldest and strongest PIPE

This little volume is gratefully and affectionately dedicated.

In the preface he wrote: “What readers ask for nowadays in a book is that it should improve, instruct, and elevate. This book wouldn’t elevate a cow. I cannot conscientiously recommend it for any useful purpose whatever.”

Notwithstanding this, he proves that a humorist can see as clearly as anyone the deep, true side of human life. For example:

Vanity. Most of us are like Mrs. Poyser’s bantam cock that fancied the sun got up every morning to hear him crow. Those fine, sturdy John Bulls “who hate flattery, sir!”

“Never let anybody get over

me

by flattery”, etc., etc., are very simply managed. Flatter them enough upon their absence of vanity, and you can do what you like with them.

The Weather: The weather is like the Government, always in the wrong. If it is fine, we say the country is being ruined for want of rain. If it docs rain, we pray for fine weather. If December passes without snow, we indignantly demand to know what has become of the good, old-fashioned winters, and talk as though we had been cheated out of something we had bought and paid for, and when it does snow, our language is a disgrace to a Christian nation.

Babies: The nurse-girl who sent Jenny to see what Tommy and Totty were doing, and “tell ’em they mustn’t”, knew infantile nature. Give an average baby a fair chance, and if it doesn’t do something it oughtn’t to, a doctor should be called in at once.

Then there is the casual reference to the Irishman who, seeing a crowd collecting, sent his little girl out to ask if there was going to be a row—”’Cos, if so, father would like to be in it”.

Also to “The Society for the Suppression of the Solo-Cornet Players in Theatrical Orchestras”.

“Idle Thoughts” was a great success. Each thousand copies constituted an “edition”, and in less than twelve months the twenty-third edition was announced. Jerome received a royalty of two-pence-halfpenny a copy. He said at the time that he “dreamed of a fur coat”. Charles Dickens was paid £29 for the first two numbers of “Pickwick” when it was published in monthly parts; on the strength of this he got married. The success of “Idle Thoughts” led Jerome to do the same.

“Three Men in a Boat”, illustrated by A. Frederics, was written in the top room of a house in Chelsea Gardens shortly after his marriage. This, like “Idle Thoughts”, was first published in

Home Chimes.

In serial form, however, it did not attract very much attention. Charles Dickens had the same experience when “David Copperfield” appeared in

Household Words.

It in no way increased the circulation of the journal.

Jerome’s original intention was to write a historical and descriptive work to be called “A Story of the Thames”. He had no idea of writing a funny book, but fortunately his sense of humour ran away with him, and he succeeded in producing a masterpiece which made him famous the world over.

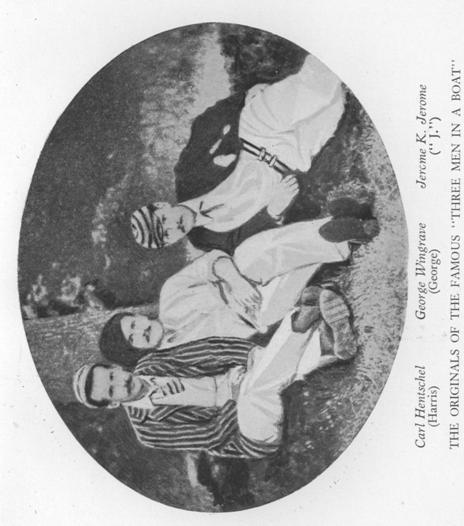

The “three men” were Jerome K. Jerome (“J”), Mr. Carl Hentschel (whose name for the purpose of the book was changed to “Harris”), and Mr. George Wingrave (“George”).

Carl Hentschel was a gifted organizer, and he has made full use of his gift all through his life. His earliest attempts in that direction were organizing on Saturday afternoons and Sundays trips along the River Thames. These expeditions were frequent, extending over several years. Mr. Hentschel states that nearly the whole of “Three Men in a Boat” is founded upon incidents that actually took place.

In the preface Jerome says: “Other books may excel this in depth of thought and knowledge of human nature; other books may rival it in originality and size, but for hopeless and incurable veracity, nothing yet discovered can surpass it.” Later in the book he refers to Queen Elizabeth’s habit of patronizing public-houses:

There’s scarcely a pub of any attractions within ten miles of London that she does not seem to have looked in at, or stopped at, or slept at, some time or other. I wonder now, supposing Harris, say, turned over a new leaf, and became a great and good man, and got to be Prime Minister, and died, if they would put up signs over the public-houses he patronized. “Harris had a glass of bitter in this house”; “Harris had two of Scotch cold here in the summer of’88”; “Harris was chucked out of here in December, 1886”.

No, there would be too many of them! It would be the houses that he never entered that would become famous. “Only house in South London that Harris never had a drink in!” The people would flock to it to see what could have been the matter with it.

The fact is, “Harris” was the only teetotaller of the party. On one of their trips he accidentally tasted a sip of something well diluted with water, and that incident, if a War-time expression may be permitted, caused “J.” to go off at the deep end, and indulge in the above good-natured banter.

Here is another example of their “fun”, this time at George’s expense:

Rather an amusing thing happened while dressing that morning. I was very cold when I got back into the boat, and, in my hurry to get my shirt on, I accidentally jerked it into the water. It made me awfully wild, especially as George burst out laughing. I could not see anything to laugh at, and I told George so, and he only laughed the more. I never saw a man laugh so much. I quite lost my temper with him at last, and I pointed out to him what a drivelling maniac of an imbecile he was, but he only roared the louder, and then, just as I was landing the shirt, I noticed that it was not my shirt at all, but George’s, which I had mistaken for mine; whereupon the humour of the thing struck me for the first time, and I began to laugh, and the more I looked from George’s wet shirt to George, roaring with laughter, the more I was amused, and I laughed so much that I had to let the shirt fall back into the water again.

“Ar’n’t you — you — going to get it out?” said George between his shrieks.

I could not answer at all for a while, I was laughing so, but at last, between my peals, I managed to jerk out: “It isn’t my shirt — it’s yours!” I never saw a man’s face change from lively to severe so suddenly in all my life.

“What!” he yelled, springing up. “You silly cuckoo! Why can’t you be more careful what you’re doing? Why the deuce don’t you go and dress on the bank? You’re not fit to be in a boat, you’re not. Gimme the hitcher.”

I tried to make him see the fun of the thing, but he could not. George is very dense at seeing a joke sometimes.

The dog, Saint Montmorency, contributed much to the amenities and humour of the expedition. Mr. Jerome wrote of Montmorency as follows:

When first he came to live at my expense I imagined he was an angel; I never thought I should be able to get him to stop long. [The artist who drew a picture of Montmorency represented him with a halo around his head.] I used to sit down and look at him as he sat on the rug and looked up at me, and think: “Oh, that will never live. He will be snatched up to the dog-skies in a chariot, that is what will happen to him.”

But when I had paid for about a dozen chickens that he had killed, and had dragged him, growling and kicking, by the scruff of his neck, out of a hundred and fourteen street-fights, and had had a dead cat brought round for my inspection by an irate female who called me a murderer, and had been summoned by the man next-door-but-one for having a ferocious dog at large, and had learned that the gardener, unknown to myself, had won thirty shillings by backing him to kill rats against time, then I began to think that maybe they’d let him remain on earth a bit longer after all.