Delphi Complete Works of Jerome K. Jerome (Illustrated) (Series Four) (509 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Jerome K. Jerome (Illustrated) (Series Four) Online

Authors: Jerome K. Jerome

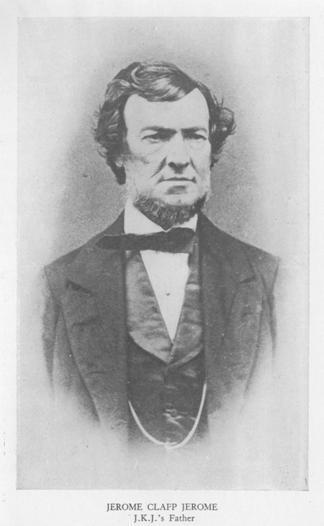

At Appledore he appears to have dropped his surname Jerome, and, whether spoken or written, his name was always the Rev. Jerome Clapp, or “Parson Clapp”. An old resident of Appledore, Mr. Thomas Ackland, who, at the time of writing, is in his 90th year, states that he worked for the Rev. Mr. Clapp on his farm, and remembers him well. He states that on one occasion when Mr. Clapp had consented to lecture, on being asked for the title, he noticed a board in front of a house on which were the words in big letters, “Power to let, enquire within”. “That,” he said “will do for the title.” Mr. Ackland states that the lecture was very amusing, and so successful that he was requested to repeat it, but did not do so.

Mr. Jerome was well-to-do; he built his own house, which he named “Milton”, and occupied his spare time in farming. It was suggested to him by a Scottish miner that silver ore was to be found on his estate. This led to Mr. Jerome’s first mining adventure, in which a good deal of money, which no doubt belonged to his wife, was lost. He appears to have been successful in his religious work, and it was unfortunate for him and for his family that he did not devote his energies entirely to it. In 1855 he left Appledore, and settled at Walsall as a partner in the Birchills Iron Works. He joined the Bridge Street Congregational Church there, and was later elected to the office of deacon.

These were stirring times for Nonconformists. The persecutions through which they were passing were, owing to the influence of Wesley, Whitfield, and others, less bitter than they had been for a long series of years. But they were still smarting under the memory of unjust and oppressive Acts of Parliament of the Restoration period, some of which, although not enforced, were unrepealed.

The Rev. T. Grove, M.A., a former minister of Bridge Street Congregational Church, had been expelled from Oxford University for offering up extempore prayer, it was said, in a barn. This was his only offence. His life was exemplary, his character good, his attainments unquestionable, his behaviour humble and peaceable; but he offered an extempore prayer, it was said, in a barn. The authorities of Oxford could, at that time, tolerate many things — laziness, drunkenness, blasphemy — but not extempore prayer in a barn. So Mr. Grove had to leave the University. The object of these University regulations was, of course, to render powerless the efforts of Nonconformists.

Mr. Jerome was moved very deeply by such injustices, and he seems to have devoted this period of his life to the removal of what was left of them. In this cause his voice and pen were very active. In January, 1857, events did not run smoothly at Bridge Street Church. Mr. Jerome and about twenty of the most zealous workers seceded. This small body of enthusiasts used to assemble for worship in the New Inn club-room. Mr. Jerome conducted the services. This action on the part of the seceders of Bridge Street caused a great commotion in the town. In a short time the club-room could not accommodate the congregation, and they removed to the Guildhall Assembly Room, Mr. Jerome’s remarkable eloquence attracting large congregations.

During the time they worshipped at the Guildhall Room, the congregation of a neighbouring chapel also became uneasy about the orthodoxy of their minister, the Rev. A. A. Cole, and many of them joined Mr. Jerome’s cause. The Guildhall Room soon became inadequate for the congregation, and they subsequently built for themselves the Bradford Street (now the Wednesbury Road) Congregational Church. Mr. Jerome was the architect, and planned the building on the model of a church at Bideford, near Appledore. He suggested that the new church should be named “Ephratah” (ancient name of Bethlehem-Judah). This suggestion was not adopted, although for many years some people called it by that name. This edifice had distinct and unique architectural features, which unfortunately were destroyed by German Zeppelins during the Midland air raid in January, 1916.

The church was rebuilt, and care was taken to restore its original features. Mr. Jerome also drafted the plans for the Congregational Church in North Street, Walsall.

Contrary to expectation, he did not become the first minister of the new church in Wednesbury Road, but his friends, Mr. E. T. Holden (afterwards Sir Edward Holden) and Mr. Elijah Stanley, and others who left the old Bridge Street Church with Mr. Jerome, remained staunch supporters of the cause as long as they lived.

Instead of becoming the first minister, Mr. Jerome entered upon a second venture in the mining industry which proved a disastrous failure. He sank two coal pits situated in Hednesford Road, Norton Canes, now known as “the Conduit Pits Nos. 9 & 10”. The work was carried on until running sand and water were met with. To cope with this additional capital was needed, which Mr. Jerome did not possess, and he was a ruined man. The pits were subsequently taken over by Messrs. Holdcroft and Fellows. The beam engine installed by Mr. Jerome is said to be still in operation as a stand by. Coal has been wound continuously ever since, and the collieries have no doubt been a profitable undertaking. Many people still refer to them as “Jerome’s pits”.

Jerome Clapp Jerome’s second name was given him after one Clapa, a Dane, who lived in the neighbourhood of Bideford, Devonshire, about the year A.D. 1000. Clapa owned property there, and some years ago relics were discovered near a ruined tower which proved beyond all doubt that the said Clapa was the founder of the Jerome House. Even at that early period there was a family crest, which was an upraised arm grasping a battle axe, the motto being

Deo omnia data.

Mr. Jerome Clapp Jerome claimed relationship to Leigh Hunt. The present writer has been unable to trace what the relationship was; it may have been somewhat distant. In any case, there were certain resemblances between the talents of the Leigh Hunt and the Jerome families, which are very interesting. Leigh Hunt’s father and Jerome K. Jerome’s father were both popular preachers, both were unpractical, and had serious financial embarrassments; while their mothers were both of Puritan extraction and were deeply religious, refined and tender. Leigh Hunt said his mother was “a serene and inspiring influence, which animated in him the love of truth”. Jerome K. Jerome said much the same of his mother.

The resemblances between the two distinguished sons of these parents must also be noted. Leigh Hunt and Jerome K. Jerome both experienced much poverty in their early days, both published humorous books, both wrote plays which became extremely popular, both were journalists of high repute, both used their influence mainly on behalf of suffering humanity, both experienced an unsympathetic and even hostile press, both had a “firm belief in all that is good and beautiful, and in the ultimate success of every true and honest endeavour”.

These resemblances show that a man cannot altogether escape from the influence of his ancestors. The lines along which he develops are more or less predetermined for him. A definite kind of talent is often transmitted through several generations, as, for instance, the musical talent of the Bach family. John Locke held that all children were born with equal abilities, and the differences which afterwards developed were due to environment and education. The newer psychology holds, perhaps rightly, that there are original differences, due to “nature” as distinguished from “nurture”. The stronger the natural intellectual bent the more readily will it find its right place in the world, and persist in the face of every discouragement.

CHAPTER II. CHILDHOOD

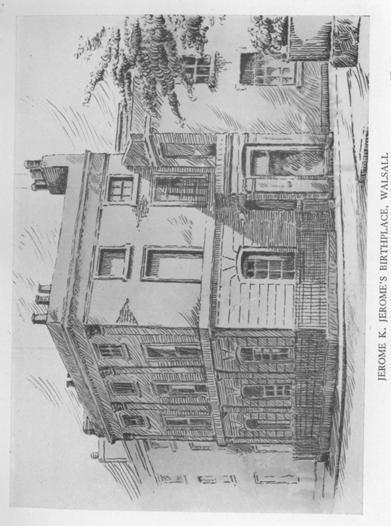

A HALO of romantic interest always surrounds the birthplaces of distinguished men. The house in Bradford Street, Walsall, where Jerome Klapka Jerome was born, has now upon its front wall a tablet bearing the following inscription:

“In this house Jerome K. Jerome was born on the 2nd May, 1859.”

Jerome’s first name was given him, of course, after his father; his second one is not a variation of his father’s second name, as is often supposed, but is after a famous Hungarian general, George Klapka, who was an exile, and was frequently a guest of the Jeromes. Some ten years previously, during the Hungarian War of Independence, this courageous young general, only twenty-nine years old at the time, held the fort of Komorn against the united Austrian and Russian armies, and only surrendered when he had secured honourable terms for his soldiers. This was on October 3rd, 1849. After the surrender, General Klapka came to London. On his arrival, Francis Pulezky (secretary to Kossuth, the leader of the Hungarian insurrection) advised him to write his memoirs. As the book had to be finished within two months, he needed a quiet retreat, and gladly accepted the invitation of Mr. Jerome Clapp Jerome, and it was in his home that Klapka’s memoirs of the “War of Independence in Hungary” were written. This book was published in 1850, and a copy is in the Walsall Public Library. Klapka visited the Jeromes in Walsall, and in all probability was with them at the time of their youngest son’s birth, and in honour of their famous guest named him Jerome Klapka.

The present writer has been fortunate enough to discover two or three aged persons who knew Jerome’s parents personally. Mrs. Jerome is invariably spoken of as a “deeply religious woman”, and as being “passionately devoted to her children”. She was evidently one of those mothers who, at the cradle side, instil into the child principles which can never be altogether departed from. They may for a time be lost sight of, but the mother’s legacy is written indelibly on the heart of the child. Her distinguished son, long after she had gone to rest, paid a fine tribute to her unfailing love in his last book, “My Life and Times”. On another occasion he stated that whenever he visited his birthplace he never failed to raise his hat in memory of his mother.

Mrs. Jerome used to keep a diary, and in it is recorded the fact that on the first anniversary of little Jerome’s birthday, when her husband came home at night, sitting on the side of her bed, he broke the news as gently as he could of the disaster that had befallen them — that the pits were inundated, and that they were ruined. For the parents, this, indeed, was the beginning of sorrows. Poverty and privation now stared them in the face, and continued to do so almost as long as they lived.

There were four children, two elder daughters, Paulina Deodata and Blandina, also a son, Milton Melanchthon, who was four years old when Jerome Klapka was born. When the latter was about two years old the family removed from Walsall to Stourbridge. (Another famous Midlander, Dr. Johnson, also removed to Stourbridge for a short time in his boyhood.) The Jeromes suffered great hardships there. The struggle for a livelihood was severe. But another calamity befell them, which to Mrs. Jerome was far greater than the loss of their money and property. Their elder son Milton was taken ill and in a few days died. His mother was almost overwhelmed with grief. On each anniversary of his death she used to write in her diary that she was another year nearer finding him again. The last entry, written sixteen years afterwards, and just ten days before she herself died, is as follows: “Dear Milton’s birthday. It can be now but a little while longer. I wonder if he will have changed.”

His remains were interred in the burial-ground behind the High Street Congregational Church, Stourbridge. A tombstone there has the following inscription upon it:

“MILTON MELANCHTHON JEROME.

He increased in wisdom and stature, in favour with God and man.

Born June nth, 1855. Died January 26th, 1862.”

Mr. Jerome Clapp Jerome had previously gone to London by himself, and, in the hope of retrieving their fortunes, worked hard for nearly two years trying to establish an ironmongery business in Narrow Street, Limehouse. Mrs. Jerome, who was still at Stourbridge, hearing that the business was not prospering, decided to take the family to London so that she might help to look after things herself.

This journey to London must have left a vivid impression on Jerome’s young mind, for long after, in 1923, he contributed an article to

The Daily News

in which he recalls his experiences of the journey as follows:

“The houses slid away, and it seemed to me that I had been wafted into a new world. ‘Surely this must be the Fourth Dimension,’ I might have said to myself, had I known then what the Fourth Dimension was, which I still don’t. Anyhow, it was something I had never dreamed of. At Stourbridge, as a little chap, I must have seen trees and fields and streams, but I had forgotten them.”