Delphi Complete Works of Jerome K. Jerome (Illustrated) (Series Four) (506 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Jerome K. Jerome (Illustrated) (Series Four) Online

Authors: Jerome K. Jerome

When did it happen, this new birth of man, through which he acquired kinship with God, also? At what turning-point of man’s story first came the thought to him: “What am I? Whence came I? Whither goeth?” How long had man been wandering upon earth before he discovered the unseen land around him, and made himself a grave to mark the road?

The desire — the intuitive belief in a future state must have grounds for its growth, or it would not have taken root in us. If our souls, like our bodies, were to be dissipated, we should not possess this instinct: it would be useless to us — a hindrance. The stoics were prepared to face the possibility; but that was that they might be free from all fear. They acknowledged that God moved in them. Their ideal was absorption back into the Godhead — the Nirvana of the Buddhists. It may be so. Eternity is a long lane. It may lead to rest.

But surely labour will come first. Kant put the moral law within him and the starry firmament above him as parts of the same whole. Man’s soul must have been given to him that he should become the helper — the fellow-labourer with God. The building of the Universe is not completed. God is still creating.

That a man shall so spend his life that, when he leaves it, he shall be better fitted for the service of God, that surely is the explanation of our birth and death.

The battle of life is a battle not for, but against self. One has not to subscribe literally to the book of Genesis to accept the doctrine of original sin. How sin came into the world, we shall know when we have learnt the secrets of Eternity. Meanwhile, our business is to fight it. By wrestling with it, we strengthen our souls. Of all who have been given power to help man in his struggle for spiritual existence, one must place Christ Jesus as the highest. As a child, I had been taught that Christ was really God. There was some mystery about a Trinity, which I did not understand — which no one ever has understood, which the early Church wisely forbade its votaries from even trying to understand. Christ, himself I could have loved. I doubt if any human being has ever read or heard his story without coming to love him — certainly no child. It was thinking of him as God that caused me to turn away from him. If all the time he was God then there had been no reality in it. It had all been mere play-acting. If Christ was God, what help to me the example of his life?

But Christ my fellow-man — however far above me — was still my brother, sharer of my bonds and burthens. From his sufferings, I could learn courage. From his victory, I could gather hope. What he demanded of me, that I could give. Where he led, I too might follow.

The Christ spirit is in all men. It is the part of man that is akin to God. By listening to it, by making it our guide, we can grow more like to God — fit ourselves to become His comrade, His fellow-labourer. By neglecting it, by allowing it to be overgrown with worldliness, stifled under the evil that is also within us, we can destroy it. That the wages of sin is death is literally true. Sin drives out the desire for God. If we do not seek Him, we shall not find Him. Christ was the great Exemplar. By his teaching, by his life and death, he showed us how a man may become truly the Son of God. All the rest makes only for confusion. The idea that Christ was sent into the world to be the scapegoat for our sins is not helpful. If God has no further use for us — if all that awaits us is an eternal idleness, to be passed in either bliss or pain, the doctrine might conceivably be comforting. But if it is for labour that God is seeking to prepare us, then it is but a stumbling-block.

It is not our sins that will drag us down, but our want of will to fight against them. It is from the struggle, not the victory, that we gain strength. “Not what I am, but what I strove to be, that comforts me.” It was not that we might escape punishment, win happiness, that we were given an immortal soul. What sense would there have been in that? Work is the only explanation of existence. Happiness is not our goal, either in this world or the next. The joy of labour, the joy of living, are the wages of God. Those realms of endless bliss in which, according to popular theology, we are to do nothing for ever and ever, one trusts are but a myth — at least, that they will still recede as we advance. Perfect rest, perfect content, can only be the final end, when all things shall have been accomplished, and even thought has ceased. Until that far-off twilight of creation, we trust that, somewhere among His many mansions, God will find work for us, according to our strength.

To prepare ourselves for the service of God: for that purpose came we into the world. How have we quitted ourselves? How have we prospered? Who among us dare hope to meet The Master, face to face, with head erect, saying, “Lord, I have done my best”?

But if we have truly sought Him, let us not lack courage. It may be, in some contest by ourselves forgot, that we won further than we knew. Where we have succeeded, He will remember. And where we have failed, we trust He, understanding, will forgive.

The Biography

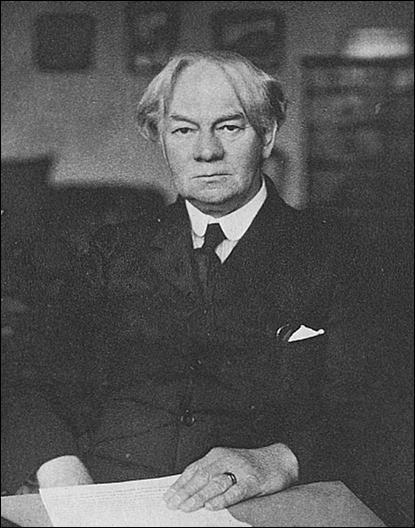

Jerome, c. 1924

JEROME K: JEROME: HIS LIFE AND WORKS by Alfred Moss

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION by Coulson Kernahan

CHAPTER V. JEROME K. JEROME AS A JOURNALIST

CHAPTER VI. JEROME K. JEROME AS A DRAMATIST

CHAPTER VII. JEROME K. JEROME’S HUMOROUS WRITINGS

CHAPTER VIII. JEROME K. JEROME AS A SERIOUS WRITER

JEROME K. JEROME

His Life and Work (From Poverty to the Knighthood of the People)

by

ALFRED MOSS

with an Introduction by COULSON KERNAHAN

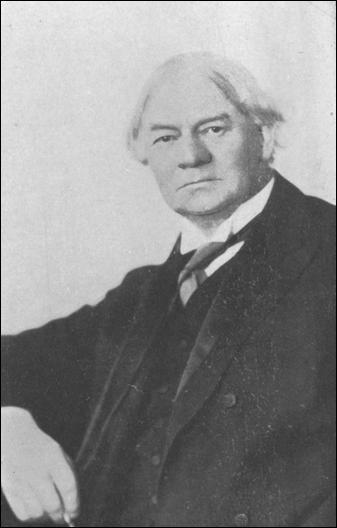

The original frontispiece

DEDICATED,

WITH PROFOUND RESPECT, TO

MRS. AND MISS JEROME

INTRODUCTION by Coulson Kernahan

I

BEFORE me lies the volume for 1887 of a magazine to which Swinburne, Watts-Dunton, J. M. Barrie, Zangwill, Eden Phillpotts, G. B. Burgin, W. H. Hudson, St. John Adcock, Jerome, and, by way of contrast, even so obscure a writer as myself, contributed. On page 320, over the signature, “Jerome K. Jerome”, I read:

“I remember one evening, not long ago, sitting in this very room of mine, with one or two boys. It was after supper, and we were smoking and discussing plots — I don’t mean revolutionary or political plots, necessitating slouch hats, black cloaks, and a mysterious walk, but plots to harrow up the feelings of magazine readers and theatrical audiences. Poor Philip Marston was one of us, and he, puffing contentedly at a big cigar, sketched us, Traddles-like, the skeleton of a tale he meant to write. There was dead silence when he had finished, and I felt hurt, because it was precisely the same plot that I had thought out for a tale I meant to write, and it seemed beastly unfair of Marston to go and think it out, too. And then young Coulson Kernahan got up, and upset his beer, and fished out, from my bookshelves, an old magazine with the very story in it. He had been and sneaked it from both of us, and published it two years before.”

And now I, who am no longer “young”, am, in fact, a fogey, am asked to write an Introduction to a Life of Jerome. The invitation recalls something told me by the late Sir Frederick Bridge. When he was a little lad at Rochester, he met, on most mornings, while trudging to school, a bluff and bearded man who was taking his dog for a run, and whom Bridge took for a sailor.

“Little did that small schoolboy think,” added Bridge, “that he would, one day, be at the organ when that man, Charles Dickens, was laid to rest by a mourning nation, in Westminster Abbey.”

I record what Sir Frederick told me for the reason that the author of “Paul Kelver” believed that, as a boy, he talked with a stranger who was no other than the author of “David Copperfield”.

II

Before writing of Jerome, I ask the reader to permit me to say something about the author of the present book. I have not asked Mr. Alfred Moss’s permission because I question whether it would be accorded. He and I have corresponded though we have never met, but from our correspondence I am sure that he is one of the most modest of men, and would prefer to remain in the background. Hence in sending him what I am now writing, and that he has not yet seen, I shall say: “Either my words about the author of the book appear — or you must try to persuade Sir J. M. Barrie, Mr. Eden Phillpotts, Mr. G. B. Burgin, or Mr. Carl Hentschel, who could say what is necessary far better than I can say it, to write the Introduction.” My first word, then, is about Mr. Moss. As many of my wife’s and my own friends are Staffordshire-born, she and I have recently been reading “Staffordshire Poets” in

Poets of the Shires Series,

edited by Charles Henry Poole, LL.D., and Russell Markland, Phil. B. On page 324 is an article on Mr. Moss, from which I learn that “He went to Oxford and pursued his studies of the classics, until, forced by the stress of circumstances, he adopted a commercial career”, and that “while he was enabled entirely by his own efforts to build up a highly successful business with far-reaching connections, he did not neglect the higher aims of life, but devoted his leisure to the study of literature and the cultivation of the art of music.... His passionate love of music led him to place himself under Dr. Swinnerton Heap, of Birmingham, for guidance in musical composition and playing, and, in singing, under the famous tenor of the mid-Victorian period, Sims Reeves.... But the sister art of poetry had always an equal attraction for him. His war-hymn ‘Repentance and Hope’, which he himself set to music, found wide acceptance among congregations of diverse creeds, both at home and abroad. It was used in many churches during the great united services on ‘Remembrance Day’ (1918) the anniversary of the outbreak of War. It will doubtless find a place in the standard hymnals of the future, together with other hymns from Mr. Moss’s pen which have been sung on various occasions of national supplication during the War, and which have been set to music by the late Sir Frederick Bridge, organist of Westminster Abbey, and by Mr. John Ireland. His finely-written poem, ‘The Silent Navy’, was published in the Naval Magazine,

Sea Pie.”

From the same source I learn that Mr. Moss has edited an “Anthology of Walsall Poetry”, and was the founder of, and the leading spirit in, the first South Staffordshire Musical Festival (1921) of which His Majesty the King, and Her Majesty the Queen, were Patrons.

III

When Mr. Moss asked me to write an Introduction to this book on Jerome, two instances of unconventional introductions occurred to me. One was when Jerome’s and my old friend, Israel Zangwill, penned an Introduction to one of his own books thus: “The Reader — my Book. My Book — the Reader.” The other was even more unconventional. His late Majesty, King Edward the Seventh, while on a visit to a great country mansion, took a stroll one morning through a neighbouring village. Noticing that one of two working men, who were standing together, had a fine war record, as witnessed by the medals he was wearing, the late King who — like our beloved present King, and his beloved eldest son — was keenly interested in ex-Service men, stopped to ask: “Where did you get that now rarely-seen decoration?” pointing to one of the medals.