Deadly Choices: How the Anti-Vaccine Movement Threatens Us All (17 page)

Read Deadly Choices: How the Anti-Vaccine Movement Threatens Us All Online

Authors: Paul A. Offit M.D.

BOOK: Deadly Choices: How the Anti-Vaccine Movement Threatens Us All

9.26Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

The special masters also revealed a more sinister aspect of the vaccines-cause-autism hypothesis—there was money to be made promoting it. No single expert better represented this unseemly side of the controversy than a Florida-based physician named Jeff Bradstreet, a witness in the trial of Colten Snyder. Bradstreet had promoted several cures for autism including secretin (a hormone made by intestinal cells to stimulate the secretion of pancreatic juices), chelation (to rid the body of mercury), immunoglobulin (administered by mouth and by vein), and prednisolone (a potent steroid that suppresses the immune system). He also prescribed dietary supplements he sold in his office. As noted by the special master, “The nutritional supplements prescribed by Dr. Bradstreet were also sold by Dr. Bradstreet.” Bradstreet had taken care of Colten Snyder for eight years, during which time Colten had visited his office one hundred and sixty times. Bradstreet had ordered laboratory tests (many of which were not approved by the FDA); and he had performed several spinal taps and inserted fiberoptic scopes into Colten’s stomach and colon. All these tests and procedures were expensive, potentially dangerous, and—according to the opinions of expert witnesses—of no value to the child.

One year after the verdicts on the first theory had been filed, on March 12, 2010, the special masters ruled on the second theory proposed by the plaintiffs: thimerosal alone caused autism. Again, their verdict was unequivocal. They ruled that the theory was “scientifically unsupportable,” and the evidence “one-sided.” And they remained angry at the cottage industry of false hope that had sprung up around children with autism, writing, “[Many parents] relied upon practitioners and researchers who peddled hope, not opinions grounded in science and medicine.”

The special masters had delivered a fatal blow to the vaccines-cause-autism hypothesis. But who really lost? It certainly wasn’t the plaintiffs’ experts. Although singled out for their lack of expertise and of personal integrity, all will likely testify in future trials, charging handsomely for their services. And it wasn’t doctors like Arthur Krigsman, referred to by a special master as one of the “physicians who are guilty, in my view, of gross medical misjudgment.” Krigsman will likely continue to offer “cures” for children with autism. Or doctors like Jeff Bradstreet, who will continue to sell dietary supplements and perform endoscopies and spinal taps on children whose parents believe in him, and are more than willing to pay out-of-pocket for his services. And it certainly wasn’t the plaintiffs’ lawyers, who will continue to try their cases in vaccine court and collect their fees independent of whether they win or lose. (The law firm of Conway, Homer and Chin-Caplan submitted a bill to vaccine court for $2,161,564.01.) Rather, the losers were Theresa and Michael Cedillo and their daughter Michelle, Rolf and Angela Hazelhurst and their son Yates, and Kathryn and Joseph Snyder and their son Colten. Under the misdirection of doctors and lawyers, these parents had come to vaccine court looking for relief from the financial burden of caring for their autistic children. But they’d come to the wrong place. Even setting aside the fact that vaccines don’t cause autism, providing services for parents of autistic children through the VICP would have been an ineffective way of getting these children what they needed. Also, it would have unfairly excluded autistic children who hadn’t been vaccinated. If doctors and lawyers in the Omnibus Autism Proceeding really cared about the autistic children they represented, they would have directed their time, energy, and money toward finding mechanisms to provide needed services. But they didn’t. And that’s because the anti-vaccine movement had taken the autism story hostage—scaring parents about vaccines; providing a source of revenue for personal-injury lawyers with direct ties to anti-vaccine activists; and driving patients into the waiting arms of anti-vaccine doctors who sold false hope, usually directly out of their offices. Many in the autism community were angry that anti-vaccine activists had diverted so much attention away from the real cause or causes of autism.

The Omnibus Autism Proceeding showed just how far public health officials and academia had come since the days of

DPT: Vaccine Roulette

. In 1982, when Lea Thompson claimed pertussis vaccine caused brain damage, science hadn’t advanced far enough to challenge her contention. During the next twenty-five years, studies showed that children who received pertussis vaccine weren’t at greater risk of permanent brain damage and that the real cause of the damage was a defect in how brain cells transported certain elements, such as sodium, across the cell membrane. Unfortunately, by the time scientists figured this out, many companies had permanently abandoned vaccines. The vaccines-cause-autism scare was different; this time the public health community was ready. When the Omnibus Autism Proceeding started, epidemiological and biological studies had already gone a long way toward exonerating vaccines. The science was in, and the special masters knew it. One stated, “The Omnibus Autism Proceeding began in 2003 with a plea by the Petitioners’ Steering Committee to ‘let the science develop.’ The science has developed in the intervening years, but not in the petitioners’ favor.”

DPT: Vaccine Roulette

. In 1982, when Lea Thompson claimed pertussis vaccine caused brain damage, science hadn’t advanced far enough to challenge her contention. During the next twenty-five years, studies showed that children who received pertussis vaccine weren’t at greater risk of permanent brain damage and that the real cause of the damage was a defect in how brain cells transported certain elements, such as sodium, across the cell membrane. Unfortunately, by the time scientists figured this out, many companies had permanently abandoned vaccines. The vaccines-cause-autism scare was different; this time the public health community was ready. When the Omnibus Autism Proceeding started, epidemiological and biological studies had already gone a long way toward exonerating vaccines. The science was in, and the special masters knew it. One stated, “The Omnibus Autism Proceeding began in 2003 with a plea by the Petitioners’ Steering Committee to ‘let the science develop.’ The science has developed in the intervening years, but not in the petitioners’ favor.”

In the 1980s, anti-vaccine crusaders—through a series of devastating lawsuits—drove many vaccine makers out of the business; as a consequence, only a handful remain. This, at least in part, has contributed to two decades of periodic shortages involving almost every vaccine. But, because of the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act, companies’ fears of litigation have almost disappeared. And, although fragile, the market for vaccines has stabilized. Another and far more damaging consequence of anti-vaccine activism has been the activists’ passionate campaign against vaccine mandates. They want to make vaccines optional. And, during the past three decades, they’ve gotten much of what they’ve wanted.

CHAPTER 7

Past Is Prologue

History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived; but, if faced with courage, need not be lived again.

—

MAYA ANGELOU

MAYA ANGELOU

I

n a sense, Barbara Loe Fisher has been around for a hundred and fifty years. That’s because the anti-vaccine movement didn’t start with the pertussis vaccine in the 1970s. It started with the smallpox vaccine in the 1850s. Remarkably, every aspect of the modern antivaccine movement—every slogan, message, fear, and consequence—has its origin in the past. But in contrast to the modern-day movement, the final outcome of the first anti-vaccine movement is known—and remains a painful, unheeded lesson in how the rights of the individual can trump the good of society.

n a sense, Barbara Loe Fisher has been around for a hundred and fifty years. That’s because the anti-vaccine movement didn’t start with the pertussis vaccine in the 1970s. It started with the smallpox vaccine in the 1850s. Remarkably, every aspect of the modern antivaccine movement—every slogan, message, fear, and consequence—has its origin in the past. But in contrast to the modern-day movement, the final outcome of the first anti-vaccine movement is known—and remains a painful, unheeded lesson in how the rights of the individual can trump the good of society.

The first vaccine prevented a disease that killed more people than any other: smallpox. The disease would start benignly with fever, headache, nausea, and backache—symptoms common to many infectious diseases. The symptoms that would follow, however, were unmistakable. The face, trunk, and limbs erupted in pus-filled blisters that smelled like rotting flesh—blisters so painful that victims felt like their skin was on fire. Worse: smallpox was highly contagious, spread easily by coughing, sneezing, or even talking. As a consequence, smallpox infected almost everyone. Pregnant women suffered miscarriages, young children had stunted growth, many were permanently blinded, and all were left with horribly disfiguring scars. One in three victims died from the disease.

“The smallpox was always present,” wrote a British historian in 1800, “filling the churchyard with corpses, tormenting with constant fears all whom it had not yet stricken, leaving on those whose lives it spared the hideous traces of its power, turning the babe into a changeling at which the mother shuddered, and making the eyes and cheeks of a betrothed maiden objects of horror to the lover.”

Smallpox killed more people than the Black Death and all the wars of the twentieth century combined; about five hundred million people died from the disease. And it changed the course of history. The virus claimed the lives of Queen Mary II of England, King Louis I of Spain, Tsar Peter II of Russia, Queen Ulrika Eleonora of Sweden, and King Louis XV of France. In Austria, eleven members of the Hapsburg dynasty died of smallpox, as did rulers in Japan, Thailand, Sri Lanka, Ethiopia, and Myanmar. When European settlers brought smallpox to North America, they reduced the native population of seventy million to six hundred thousand. No disease was more feared, more destructive, or more loathsome than smallpox.

In 1796, Edward Jenner invented a vaccine that eliminated smallpox from the face of the earth. The idea for how to make it wasn’t his.

Jenner was a country doctor working in the hamlet of Berkeley, Gloucestershire, in southern England. In 1770, a milkmaid noticed that when she milked cows with blisters on their udders—and suffered the same blisters on her hands—she was protected against smallpox during the epidemics that periodically swept across the English countryside. She confided her theory to Jenner, who, after observing the same phenomenon, decided to test it. On May 14, 1796, Jenner took fluid from a blister of another milkmaid named Sarah Nelmes. Then he injected it under the skin of James Phipps, the eight-year-old son of a local laborer. After a few days, Phipps developed a small, pus-filled blister that eventually fell off. To test the milkmaid’s theory, on July 1, 1796, Jenner injected Phipps with pus taken from someone with smallpox; Phipps survived. In a let-ter to a friend, Jenner wrote, “But now listen to the most delightful part of my story. The boy has since been inoculated for the Smallpox which, as I ventured to predict, produced no effect. I shall now pursue my Experiments with redoubled ardor.”

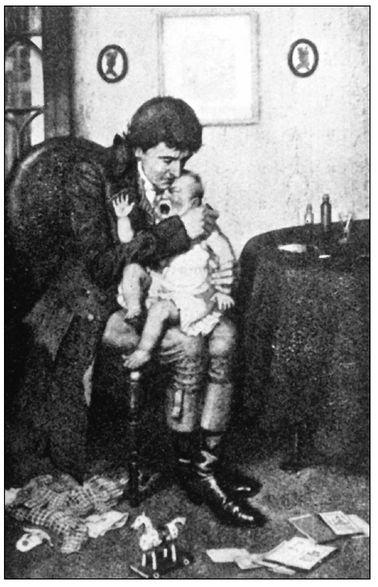

Edward Jenner inoculates his young son with smallpox vaccine. (Courtesy of Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images.)

Two years later, in 1798—after many similar experiments—Jenner published his observations in a monograph titled

Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae

. (The term

vaccination

is derived from the Latin

vaccinae

, meaning “of the cow.”) Jenner’s vaccine spread through England with remarkable speed, reaching Leeds, Durham, Chester, York, Hull, Birmingham, Nottingham, Liverpool, Plymouth, Bradford, and Manchester as well as many smaller towns. Within two years, his monograph had been translated into several languages and vaccination had spread to France, Germany, Spain, Austria, Hungary, Scandinavia, and the United States. Universally accepted by all classes, between 1810 and 1820 Jenner’s vaccine halved the number of deaths from smallpox.

Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae

. (The term

vaccination

is derived from the Latin

vaccinae

, meaning “of the cow.”) Jenner’s vaccine spread through England with remarkable speed, reaching Leeds, Durham, Chester, York, Hull, Birmingham, Nottingham, Liverpool, Plymouth, Bradford, and Manchester as well as many smaller towns. Within two years, his monograph had been translated into several languages and vaccination had spread to France, Germany, Spain, Austria, Hungary, Scandinavia, and the United States. Universally accepted by all classes, between 1810 and 1820 Jenner’s vaccine halved the number of deaths from smallpox.

Then British government officials did something that launched a movement that has never ended. They required vaccination.

The first pleas for compulsory vaccination came from a relatively unknown medical society. In 1850, a group of prominent British physicians founded the Epidemiological Society of London; their goal was to evaluate epidemic diseases under the “light of modern science.” Like all physicians in medical societies, they had intellectual interests. But unlike those in other societies, they were also political. Society members wanted to influence the state to take a greater role in public health: “to communicate with the government and legislature on matters connected with the prevention of epidemic disease.” And no disease interested them more than smallpox. Society physicians reasoned that the best way to protect the public from the ravages of smallpox was to require vaccination. So they lobbied the British Parliament for a compulsory vaccination act.

On February 15, 1853, the “Bill to Further Extend and Make Compulsory the Practice of Vaccination” was introduced in the House of Lords. The bill required all children to be vaccinated by six months of age; parents who failed to comply could be fined or imprisoned. Passage of the bill was ensured by an outbreak that, from the standpoint of the society’s physicians, couldn’t have come at a better time. Between 1810 and 1850, deaths from smallpox were in a slow, steady decline. But in 1852—the year before the bill was introduced—smallpox deaths in England and Wales increased from four thousand to seven thousand and in London from five hundred to a thousand. As a consequence, the bill passed easily and parents lined up to vaccinate their children. The rush to vaccinate didn’t last long. When parents realized that compulsory vaccination wasn’t enforced, vaccination rates fell. As a consequence, the vaccination act of 1853, described by one historian as “a damp squib,” had limited impact.

The lesson learned in 1853 resulted in a tougher law. This time the government wasn’t going to look away when parents chose not to vaccinate their children. The new act, passed in 1867, clearly defined how vaccination would be enforced and who would do the enforcing. First, medical officers would issue a warning to parents who didn’t have a certificate proving vaccination. If the warning was ignored, officers took parents to court, where they faced a stiff fine plus court costs. Because the law targeted the poor—considered less likely to vaccinate their children due to “ignorance and prejudice”—many parents couldn’t afford the fines. If parents couldn’t or wouldn’t pay, their family assets were seized and sold at public auction. And if enough money couldn’t be raised from these sales, one of the parents (usually the father) could be jailed for up to two weeks. The compulsory vaccine act of 1867 also overturned a court ruling in 1863 that only one penalty could be levied for failure to vaccinate. Now, the cycle of fines, public auctions, and imprisonment could occur again and again.

Other books

The Painting by Schuyler, Nina

Hogs #3 Fort Apache by DeFelice, Jim

Asunder by David Gaider

DARKNET CORPORATION by Methven, Ken

Book of Secrets by Chris Roberson

Man From the USSR & Other Plays by Vladimir Nabokov

The Land Agent by J David Simons

Internet Kill Switch by Ward, Keith

If Wishing Made It So by Lucy Finn

Home by Nightfall by Alexis Harrington