Deadly Choices: How the Anti-Vaccine Movement Threatens Us All (15 page)

Read Deadly Choices: How the Anti-Vaccine Movement Threatens Us All Online

Authors: Paul A. Offit M.D.

BOOK: Deadly Choices: How the Anti-Vaccine Movement Threatens Us All

9.23Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

On November 11, 1992, Werderitsch, a thirty-three-year-old nurse, received her first dose of hepatitis B vaccine; a month later, she received her second. Soon after, she suffered numbness on the left side of her body; then she lost vision in one eye. On February 2, 1993, after a series of medical tests, doctors had a diagnosis: multiple sclerosis. On May 26, 2006, a special master ruled that Dorothy Werderitsch’s multiple sclerosis was caused by hepatitis B vaccine.

The notion that hepatitis B vaccine caused multiple sclerosis wasn’t supported by the science. For one thing, the viral protein in the vaccine (hepatitis B surface protein) and the viral protein in blood found during natural infection are identical. So a disease caused by the vaccine should also be caused by natural infection. But multiple sclerosis isn’t more common in people with hepatitis B virus infections; it’s less common. Also, two large epidemiological studies, performed by researchers at Harvard’s School of Public Health and McGill University in Montreal—involving tens of thousands of subjects and published in the

New England Journal of Medicine

—found no evidence of an association. When the special master decided that hepatitis B vaccine caused Dorothy Werderitsch’s multiple sclerosis, both of these studies had already been published.

New England Journal of Medicine

—found no evidence of an association. When the special master decided that hepatitis B vaccine caused Dorothy Werderitsch’s multiple sclerosis, both of these studies had already been published.

The rulings in favor of Althen, Capizzano, and Werderitsch frightened those concerned about what could happen in the vaccine-autism cases.

Perhaps the best person to provide a look behind the curtain of the Vaccine Injury Compensation Program is Lucy Rorke-Adams, a professor of pathology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Every time a child’s death is linked to a vaccine, Rorke-Adams examines the brain. Her unusual role in the VICP is explained by her remarkable story.

Rorke-Adams is the fifth and last daughter of Armenian immigrants who barely escaped Turkish persecution. Although she was born and raised in St. Paul, Minnesota, her parents spoke only Armenian. “When I entered kindergarten, I couldn’t speak English and sat on a swing in the doorway between the classroom and cloakroom and cried,” she recalled. Between 1947 and 1957, Rorke-Adams earned a bachelor of arts, master of arts in psychology, bachelor of science in medicine, and doctor of medicine, all from the University of Minnesota. After medical school she began an internship in Philadelphia. There she met the scientist who changed the course of her career. “The chairman of pathology at Philadelphia General Hospital was William Ehrich,” she recalls. “Dr. Ehrich had been a pupil of Ludwig Aschoff, who had been taught by Frederich Daniel von Recklinghausen, who in turn was educated by Rudolf Virchow, the father of pathology. I regard myself as Virchow’s great-great-granddaughter, scientifically speaking!” (All these legendary German pathologists have been immortalized by medical terms bearing their names.)

Lucy Rorke-Adams, a neurologist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, was a key expert in cases of children suspected of suffering or dying from vaccines. (Courtesy of Lucy Rorke-Adams.)

After more than forty years in the field, Rorke-Adams is recognized as one of the world’s foremost pediatric neuropathologists, consulted by colleagues worldwide. When Albert Einstein died, she received a section of his brain to study. It is a testament to the thoroughness and rigor of defense attorneys in vaccine court that they turn so frequently to Rorke-Adams for her expertise.

Rorke-Adams has now evaluated the brains of thirty-three children who died after vaccination or whose unexplained seizures required a brain biopsy. She is still waiting for one to show that vaccines were the cause. “What I did find,” she recollects, “is a variety of abnormalities and sundry diseases that could explain what the kids had.” Rorke-Adams found that some children had died from malformations, degenerative diseases, vascular disorders, and infectious diseases; others, from accidental smotherings or child abuse. “So, the bottom line,” she says, “is that there is no evidence, in terms of scientific evaluation and now pathological evaluation, of anything that one can ascribe to a vaccine.” But despite her expertise, and despite the fact that she has supported her evaluations with cogent, well-researched opinions, Rorke-Adams often finds that petitioners prevail. And they prevail behind their principal expert: John Shane, a man who claims to be an expert in neuropathology even though according to Rorke-Adams he has no specific training or standing in the field.

Shane was the chief of pathology at Lehigh Valley, a community hospital north of Philadelphia. “John Shane has testified under oath that because he was responsible for all of the neuropathology at Lehigh Valley Hospital for forty to forty-five years, that he is an expert in neuropathology,” says Rorke-Adams. “His knowledge of the infant brain is sketchy at best. For example, he is unable to distinguish inflammatory cells, called lymphocytes, from cells in the brain of a baby that look like lymphocytes, but which are actually primitive nerve cells. In [the case of] one baby he testified that the vaccine had caused encephalitis [inflammation of the brain], when in reality the brain was entirely normal. Unfortunately, the special master hearing the case allowed herself to be convinced of this absurdity.” The cells that John Shane had confused with inflammatory cells are called “primitive neuroectodermal cells”: a cell type on which Rorke-Adams, unlike Shane, has published extensively.

Rorke-Adams described another example of Shane’s questionable expertise in evaluating infant brains. “Shane claimed that the vaccine virus had damaged myelin resulting in a demyelinating disease,” she recalled. But Shane was claiming the impossible. “Myelination of the developing nervous system is far from complete at the time of birth,” says Rorke-Adams. “[That’s why] human newborns, unlike calves or foals, cannot jump out of the womb and run around the delivery room. Although myelination isn’t complete until early childhood, it is sufficiently advanced by 12 to 18 months of age to allow a baby to crawl and start walking. However, at six months of age, certain portions of the brain have little myelin. If there is little or no myelin it isn’t possible to have a demyelinating disease. Therefore, demyelinating diseases aren’t generally found in children less than one year of age.” (Rorke-Adams is in an excellent position to know this, having published the seminal and much-referenced book

Myelination of the Brain in the Newborn

.)

Myelination of the Brain in the Newborn

.)

Shane’s problems weren’t limited to his lack of expertise in neuropathology. A lawyer friend named John Karoly asked Shane to witness a will of Karoly’s brother, Peter, written

after

Peter and his wife had died in a plane crash. Karoly wanted part of his brother’s multimillion-dollar estate; so Shane witnessed Peter’s faked signature. Unfortunately for Shane and Karoly, Peter Karoly already had a will on record. The criminal complaint against John Karoly, Jr., and John Shane was filed in U.S. District Court on September 25, 2008. According to U.S. Attorney Laurie Magid, “The defendants conspired in a fraudulent scheme to forge the wills of Peter Karoly and Lauren Angstadt in order to unlawfully benefit from their tragic deaths. Their actions were not only illegal; they subverted the true intentions of the victims.” Six months later, Karoly was charged in a $500,000 tax evasion scheme. In a plea bargain that included renouncing his claim against his late brother’s estate, the previous charges against Karoly and Shane were dropped.

after

Peter and his wife had died in a plane crash. Karoly wanted part of his brother’s multimillion-dollar estate; so Shane witnessed Peter’s faked signature. Unfortunately for Shane and Karoly, Peter Karoly already had a will on record. The criminal complaint against John Karoly, Jr., and John Shane was filed in U.S. District Court on September 25, 2008. According to U.S. Attorney Laurie Magid, “The defendants conspired in a fraudulent scheme to forge the wills of Peter Karoly and Lauren Angstadt in order to unlawfully benefit from their tragic deaths. Their actions were not only illegal; they subverted the true intentions of the victims.” Six months later, Karoly was charged in a $500,000 tax evasion scheme. In a plea bargain that included renouncing his claim against his late brother’s estate, the previous charges against Karoly and Shane were dropped.

The story of John Shane—a professional witness with questionable expertise and integrity—would be repeated in the Omnibus Autism Proceeding.

Among the first to claim that vaccines might cause autism was Barbara Loe Fisher. In

A Shot in the Dark

she wrote, “With the increasing number of vaccinations American babies have been required to use has come increasing numbers of reports of chronic immune and neurologic disorders ... including ... autism.” At the time, Fisher’s claim had little traction; few parents carried the banner. But, when a British doctor said it, everything changed.

A Shot in the Dark

she wrote, “With the increasing number of vaccinations American babies have been required to use has come increasing numbers of reports of chronic immune and neurologic disorders ... including ... autism.” At the time, Fisher’s claim had little traction; few parents carried the banner. But, when a British doctor said it, everything changed.

In 1998, Andrew Wakefield, a surgeon working at the prestigious Royal Free Hospital in London, published a paper in the well-respected medical journal

The Lancet

. The paper, densely titled “Ileal-Lymphoid-Nodular Hyperplasia, Non-Specific Colitis, and Pervasive Developmental Disorder in Children,” reported the stories of eight children with autism. Wakefield claimed that all the children had received MMR, all had symptoms of autism soon after, and all had inflammation of their intestines. In his paper, Wakefield proposed a series of events: measles vaccine entered the intestines causing inflammation; once inflamed, the intestines became leaky, allowing harmful proteins to enter the blood, travel to the brain, and cause autism.

The Lancet

. The paper, densely titled “Ileal-Lymphoid-Nodular Hyperplasia, Non-Specific Colitis, and Pervasive Developmental Disorder in Children,” reported the stories of eight children with autism. Wakefield claimed that all the children had received MMR, all had symptoms of autism soon after, and all had inflammation of their intestines. In his paper, Wakefield proposed a series of events: measles vaccine entered the intestines causing inflammation; once inflamed, the intestines became leaky, allowing harmful proteins to enter the blood, travel to the brain, and cause autism.

As a consequence of Wakefield’s paper, many parents abandoned MMR. (It is interesting to note that fears of both pertussis and MMR vaccine originated in England. “I think our media [have] a lot to do with it,” says David Salisbury, director of England’s Department of Immunization. “[The United States] has basically three newspapers that cross the country [the

New York Times

, the

Wall Street Journal

, and

USA Today

] and the rest are very much local newspapers. We have at least fifteen national-level newspapers. So our journalists are competing for coverage of a smaller population divided amongst a much greater number of papers. And I think that leads to more histrionic, more aggressive reporting to seize the audience.” Salisbury sees another connection between the pertussis and MMR scares: “The younger mothers of children who are being offered MMR were the daughters of women who had not [given them] the pertussis vaccine. So the grandmother was not a trivial person in the MMR issue.”)

New York Times

, the

Wall Street Journal

, and

USA Today

] and the rest are very much local newspapers. We have at least fifteen national-level newspapers. So our journalists are competing for coverage of a smaller population divided amongst a much greater number of papers. And I think that leads to more histrionic, more aggressive reporting to seize the audience.” Salisbury sees another connection between the pertussis and MMR scares: “The younger mothers of children who are being offered MMR were the daughters of women who had not [given them] the pertussis vaccine. So the grandmother was not a trivial person in the MMR issue.”)

Predictably, outbreaks of measles swept across the United Kingdom and Ireland, causing hundreds of hospitalizations and four deaths. In the United States, parents of a hundred thousand children chose not to vaccinate them. The worldwide panic following Wakefield’s paper caused researchers to take a closer look. Investigators found that children with autism were not more likely to have measles vaccine virus in their intestines; and they were not more likely to have intestinal inflammation. Further, no one identified brain-damaging proteins in the bloodstream of children who had received MMR. Finally, twelve separate groups of researchers working in several different countries examined hundreds of thousands of children who had or hadn’t received MMR. The risk of autism was the same in both groups. For scientists, these studies ended the concern that MMR caused autism.

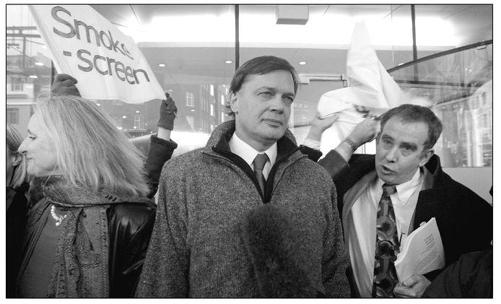

Brian Deer (right), an investigative reporter, confronts Andrew Wakefield. Deer almost single-handedly exposed improprieties in Wakefield’s research. (Courtesy of AFP/Getty Images.)

Because no one could confirm his work, Wakefield lost credibility among his colleagues. Then he suffered further disgrace. Brian Deer, a journalist working for the

Sunday Times

of London, found that the parents of five of the eight children described in Wakefield’s paper were suing pharmaceutical companies, claiming that MMR had caused autism. Deer also found that the personal-injury lawyer who represented these children, Richard Barr, had given Wakefield £440,000 (about $800,000) to perform his study, essentially laundering legal claims through a medical journal. When Wakefield’s co-authors found out about the money, ten of thirteen formally withdrew their names from the paper, distancing themselves from the MMR-causes-autism hypothesis. Finally, one of Wakefield’s co-workers, Nicholas Chadwick, testified that Wakefield had published the finding that autistic children had measles vaccine virus genes in their spinal fluid when he knew that the test was incorrect. Wakefield eventually left England, landing at a clinic called Thoughtful House in Austin, Texas, where he offered a variety of “cures” for children with autism.

Sunday Times

of London, found that the parents of five of the eight children described in Wakefield’s paper were suing pharmaceutical companies, claiming that MMR had caused autism. Deer also found that the personal-injury lawyer who represented these children, Richard Barr, had given Wakefield £440,000 (about $800,000) to perform his study, essentially laundering legal claims through a medical journal. When Wakefield’s co-authors found out about the money, ten of thirteen formally withdrew their names from the paper, distancing themselves from the MMR-causes-autism hypothesis. Finally, one of Wakefield’s co-workers, Nicholas Chadwick, testified that Wakefield had published the finding that autistic children had measles vaccine virus genes in their spinal fluid when he knew that the test was incorrect. Wakefield eventually left England, landing at a clinic called Thoughtful House in Austin, Texas, where he offered a variety of “cures” for children with autism.

Other books

The First Wave by James R. Benn

The Dating List by Jean C. Joachim

Coming Home by Amy Robyn

Haven 3: Forgotten Sins by Gabrielle Evans

My Heart be Damned by Gray, Chanelle

The Young Intruder by Eleanor Farnes

4 - Valentine Princess by Princess Diaries 4 1

Black Butterfly by Michelle, Nika

Sylvester by Georgette Heyer