Dead Men Do Tell Tales: The Strange and Fascinating Cases of a Forensic Anthropologist (43 page)

Read Dead Men Do Tell Tales: The Strange and Fascinating Cases of a Forensic Anthropologist Online

Authors: William R. Maples,Michael Browning

Tags: #Medical, #Forensic Medicine

I have no room over my laboratory door lintel for an engraved inscription, but if I did I would choose the last words of the explorer, Robert Falcon Scott, who perished in the frozen wastes of Antarctica in 1912, of hunger and exposure, in a place that was only a few miles from food and safety. The last entry in his diary read:

Had we lived, I should have had a tale to tell of the hardihood, endurance and courage of my companions, that would have stirred the heart of every Englishman. These rough notes and our dead bodies must tell the tale

.

That’s how I feel about the skeletons here in my laboratory. They have tales to tell us, even though they are dead. It is up to me, the forensic anthropologist, to catch their mute cries and whispers, and to interpret them for the living, as long as I am able.

Acknowledgments

This book could not have been written, and the life it describes could not have been lived, were it not for my wife, Margaret Kelley. Margaret and I are old comrades now. We met in Miss Berry’s Spanish class in my sophomore year at North Dallas High School. At the end of the year Miss Berry struck a deal with me: she’d give me a C if I would promise never to take Spanish again. I readily agreed. I never mastered the language of Cervantes and Calderón, but I won Margaret.

We married in 1958 and through all these years she has been the spark that has galvanized me to greater effort. It was she who persuaded me to accept a job offer to work with baboons in Africa, and take her with me, even though she was five months pregnant. Both of our children, Lisa and Cynthia, were born in Africa. She has always been the more energetic and adventuresome of us two, and her courage and patience with the outlandish side of my work has always amazed me. There is certainly no one more skilled and experienced than she is, when it comes to removing bloodstains from laundry! Nor are there many wives who could sit unflinchingly through a slide presentation of time-lapsed photography depicting the action of maggots on the human face, as Margaret once did at a convention of the American Academy of Forensic Scientists. Her clarity of intellect and strong heart have upborne me all my adult life. Without her I might have been a mere, dull measurer of bones. With her, I have never become unmoored from the lively touch of humanity.

My professional indebtedness to my old teacher, Tom McKern, and to my colleagues, old and young, such as Clyde Snow, Michael Baden, Lowell Levine, Doug Ubelaker, as well as to William Hamilton, the District 8 chief medical examiner, has already been hinted at in these pages, but I would like to re-echo it here. Without the support of the Florida medical examiners, especially Wallace Graves and Joe Davis, my story would have been sparse indeed. Special mention must be made of Curtis Mertz, of Ashtabula, Ohio, who helped me solve the puzzling Meek-Jennings case described in

Chapter 11

. Mertz assembled all the dental information, the postmortem remains, and the antemortem radiographs in this labyrinthine affair. We worked very much as a team, and the final, conclusive dental identifications are owed to his keen eye.

I owe special debts to Bob Benfer, who got me started on historical cases; to Bill Goza, expeditor and amazing resource; and to the Wentworth Foundation. The administration of the University of Florida is gratefully acknowledged.

C. Addison Pound, Jr., benefactor of the laboratory bearing his name and that of his parents, has given me the freedom to develop my interests. His continued support of the goals of this laboratory is a shining example of how a private citizen can have an impact on crime and assisting its victims.

Margaret’s help was invaluable to me in reading the manuscript and making many useful suggestions. She took several of the photographs that appear in this book, and helped me assemble the rest. I would like to acknowledge the assistance of Yale’s Beinecke Library for a photograph of Tsar Nicholas’s daughters and for access to other photographic archives. I am grateful for the help and hospitality of Dr. Alexander Avdonin, who enabled us to view and analyze the skeletons of the Tsar and his family. An earlier, shorter version of the account of the Ekaterinburg skeletons appeared in the

Miami Herald’s Tropic

magazine, and permission to reuse this material is herewith gratefully acknowledged. Our literary agent, Esther Newberg, surpassed Rumpelstiltskin in spinning gold from raw flax. Our editors at Doubleday, Bill Thomas and Rob Robertson, were enthusiastic, Argus-eyed and patient, at all the right times.

William R. Maples, Ph.D

.

Michael C. Browning

The logo of the C. A. Pound Human Identification Laboratory.

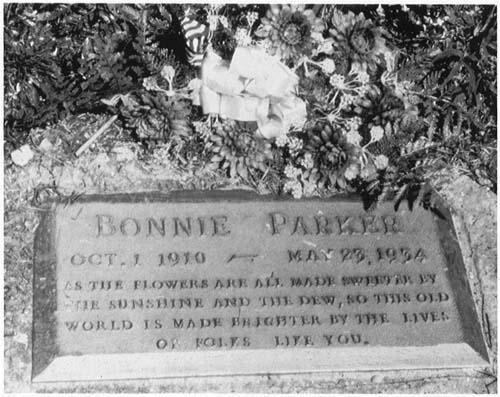

The tombstone of outlaw Bonnie Parker. Every criminal was likely loved by someone in life.

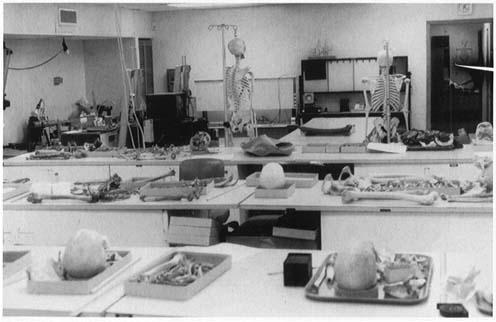

“These rough notes, and our dead bodies …” The science of forensic anthropology consists of listening to the whispers of the dead.

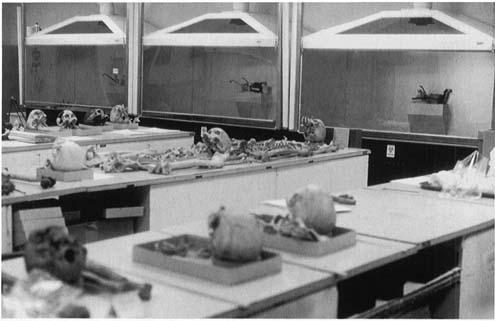

The C. A. Pound Human Identification Laboratory, showing “odor hoods.” Inside these ventilated plastic bubbles skeletal remains are boiled clean of flesh and prepared for examination.

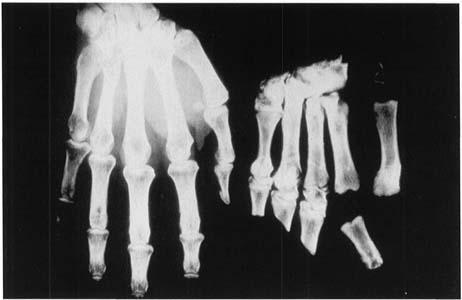

Nature’s trickery: radiographs of human hand (left) and bear paw (right).

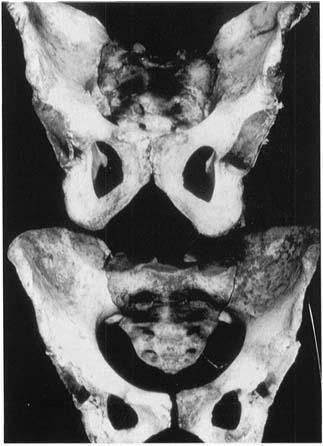

Male and female pelvises. Note that the female specimen (below) has a greater pelvic breadth and wider subpubic angle. Such distinctions are aids in what we call “sexing the skeleton.”

Human thighbones (femurs) as they progress through life. At birth the end of the bone at the knee is a separate element, or epiphysis. The epiphysis gets larger and changes its shape as growth progresses, beginning to unite with the rest of the femur. The groove, or scar, shows a femur that has recently united, signaling the end of growth. The groove disappears in an adult femur, and one might never guess the single bone had originally been several parts.

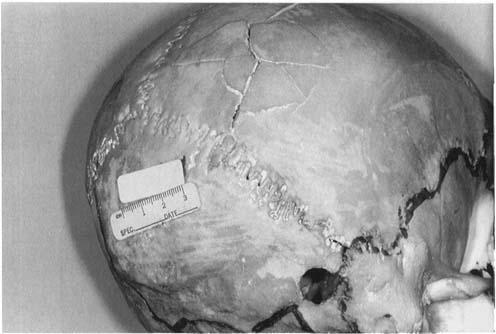

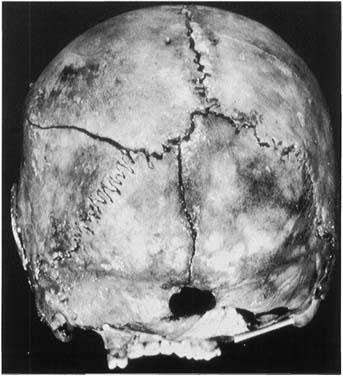

A .410 shotgun entrance wound at the base of the back of the skull.