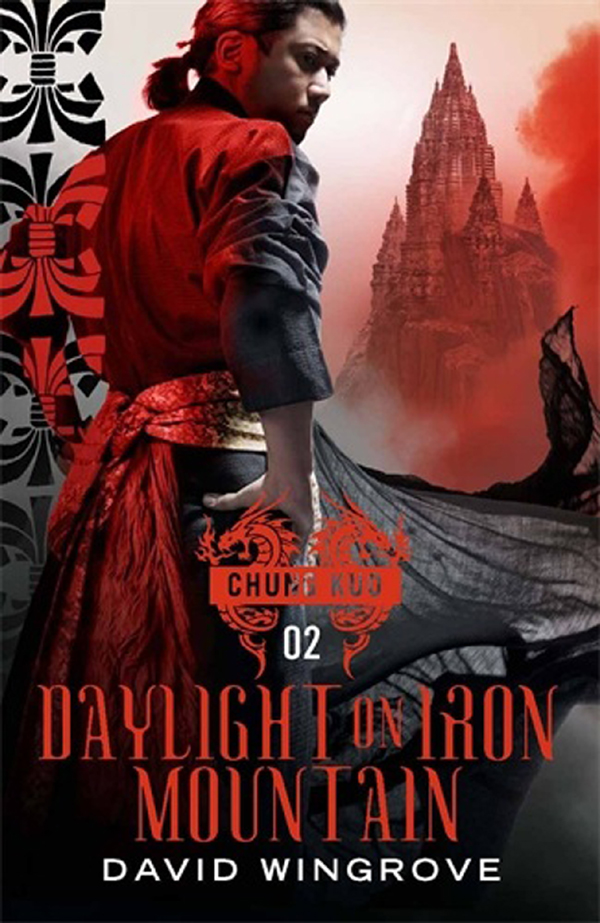

Daylight on Iron Mountain

1 Son of Heaven

1 Son of Heaven2 Daylight on Iron Mountain

3 The Middle Kingdom

4 Ice and Fire

5 The Art of War

6 An Inch of Ashes

7 The Broken Wheel

8 The White Mountain

9 Monsters of the Deep

10 The Stone Within

11 Upon a Wheel of Fire

12 Beneath the Tree of Heaven

13 Song of the Bronze Statue

14 White Moon, Red Dragon

15 China on the Rhine

16 Days of Bitter Strength

17 The Father of Lies

18 Blood and Iron

19 King of Infinite Space

20 The Marriage of the Living Dark

DAYLIGHT ON IRON MOUNTAIN

DAVID WINGROVE

DAVID WINGROVE First published in hardback and trade paperback in Great Britain in 2011 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books.

First published in hardback and trade paperback in Great Britain in 2011 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books.Copyright © David Wingrove, 2011

The moral right of David Wingrove to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination.

Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-84887-831-0

Trade paperback ISBN: 978-1-84887-832-7

ebook ISBN: 978-0-85789-432-8

Printed in Great Britain

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE Fireflies – Summer 2067

PART FOUR Black Hole Sun – Summer 2067

Chapter 12 An Interview With The Dragon

PART FIVE Daylight On Iron Mountain – Summer 2087

Chapter 19 The First Dragon Decides

Chapter 20 Scattered Memories The Age Of Waste From

Chapter 22 Tigers And Butterflies

Chapter 23 Beautiful And Imposing

Chapter 25 Daylight On Iron Mountain

EPILOGUE Lilac Time – Summer 2098

Author’s Note And Acknowledgments

née

Jackson, my loving mother, with thanks for every year of life you’ve given me. Here is another for your shelves.

| PROLOGUE | | Fireflies |

| | | SUMMER 2067 |

| | | |

| | | You who are born in decay |

| | | Dare not fly into the sun. |

| | | |

| | | Too dim to light a page, |

| | | You spot my favourite robe. |

| | | |

| | | Wind-tossed, you’re faint beyond the curtain |

| | | After rain, you’re sparks inside the forest. |

| | | |

| | | Caught in winter’s heavy frost, |

| | | Where can you hide, how will you resist it? |

| | | |

| | | —Tu Fu, ‘Firefly’ ad 750 |

AT HUA CH’ING SPRINGS

I

was the summer of 2067, that bright, hot summer before the beginning of the American campaign. And it was there, in the green shadow of Li Mountain, in that most ancient of places, Hua Ch’ing Hot Springs, sixty

li

east of China’s ancient capital, Xi’an, that they met.

Hua Ch’ing was an ancient place, even by Han standards. A sprawling summer palace, built into the green of the mountainside. First built on by the Chou more than two thousand years before, then followed by the Ch’in and Han, it was a place where Tang Dynasty emperors had once bathed, surrounded by courtiers and concubines, poets and politicians; a place of culture and long history.

Here the great poet, Tu Fu, had written his reflective poems, thirteen centuries before. Poems which still had the freshness of the dew-touched dawn.

There in the moon’s pale light on a clear and cloudless evening, beneath the ancient arch of the Fei Hung Ch’iao, ‘the Rainbow Bridge’, Tsao Ch’un floated on his back, naked as a newborn, looking up at the star-filled heavens.

From where he lay, luxuriating in the warm, sulphur-scented water, he could see the Kuei Fei, the baths of the imperial concubines, and beyond them the Lung Yin waterside pavilion. The great

Ko Ming

emperor Mao had come here once, it was said, to speak with his arch enemy, Chiang Kai-shek, whom he had captured. Since which time, history had passed this haven by.

Guards stood like dark statues beneath the locust trees that flanked the

Springs, while in a chair nearby, on the platform of the Chess Pavilion, sat the great man’s friend and advisor, Chao Ni Tsu.

This was Chao’s first visit to the Springs. He had spent the long afternoon dozing beside the pale green waters, in the shade of a silk umbrella, while Tsao Ch’un had climbed the steps that led up steeply through the trees, to visit the ancient temples that were hidden in the great tangle of green that was Mount Li.

It was more than fifty years since Tsao had come here last, as an adolescent, back when his parents had been alive. Then it had been packed with tourists, endless specimens of ‘Old Hundred Names’ who had crowded into this place designed for emperors, for calm and contemplation. The common man, smoking a cigarette and hawking up phlegm. There, six deep wherever you turned, smelling of sweat and cheap cologne. How he had loathed coming here back then. Hated the crowds, the endless gap-toothed peasants. But today…

Chao Ni Tsu smiled at the memory of Tsao Ch’un’s face as he had looked about him earlier, his eyes drinking in the simple peacefulness, the pure, unchanged beauty of the place. Yes, and the emptiness. The lack of ‘Old Mud Legs’, spoiling things just by being there.

He had ordered his guards to form a cordon about the place for the duration, then like Ming Huang himself, had pulled on his dragon robes and gone inside, like the great emperors of old.

A long silence had fallen between the two, as if the gravity of what they had been discussing had become too weighty for further discussion. But now that silence was broken, not by the man who floated beneath the ancient bridge, like a sleeping tiger, but from the one who was prone to speak but scantly in normal circumstances. Scantly and hesitantly, afraid to commit his thoughts to utterance. Only now he did, leaning towards the dark shape in the water just below him.

‘It is as you said, Tsao Ch’un. Our response must be dramatic and immediate and…

lasting

.’

Tsao Ch’un grunted. ‘You think I am right then, Brother Chao? You think we should nuke them and have done with it?’

‘I think…’ Chao hesitated. ‘I think they have made it very hard for you to follow any other path. I think… well, to be candid, I think we have two choices: To destroy them entirely, root and branch; or to license their

religion. To allow it into our City in a milder,

sanctioned

form.’

‘

Allow

it!’ Tsao Ch’un roared, the water about him growing agitated as he turned to face his old companion. ‘No, Chao Ni Tsu! Mao was right. Religion’s a disease, a malaise of the brain. It makes madmen of us all! If only we could cure it, neh? Give the bastards a pill and flush it from their minds!’ He sighed. ‘The gods help us, Master Chao! If only they’d be reasonable.’

Chao chuckled. ‘

Reasonable?

’

Tsao Ch’un reached out, grasping the carved marble edge of the steps beside the bridge.

‘You know what I mean. You’d think they’d see what was happening. That they’d recognize where the tide of history is taking us. See it and adapt, not fight it tooth and nail. You’d think…’