Dangerous to Know (3 page)

Authors: Tasha Alexander

“You've every right to be unsettled,” I said. “What is the inspector's plan?”

“He's concluded that there's no harm done and no point in looking for the culprit.”

“Madame du Lac is great friends with Monet. She could perhaps find out from him who previously owned the work. You may find you've been the victim of nothing more than a practical joke at the hands of well-meaning friends.” We called her over at once and relayed the story to her.

“Mon dieu!”

she said. “I know this painting well. It was stolen from Monet's studio at Giverny not three days agoâhe wired to tell me as soon as it happened. He'd only just finished with the canvas. The paint was barely dry and the police have no leads.”

I would not have believed, a quarter of an hour ago, that anything could have distracted me from the memory of the brutalized body beneath the tree, but suddenly my mind was racing. “Was there anything else in the note?” I asked.

“Some odd letters,” Madeline said. “They made no sense.”

“It was Greek, my darling. But I didn't pay enough attention in school to be able to read it.”

My heartbeat quickened with a combination of anxiety and unworthy delight. It could only be Sebastian.

Â

“Your imagination is running away with you entirely,” Colin said as he untied his cravat and pulled it from his starched collar. The Markhams hadn't stayed late, and Colin and I had retired to our room soon after their departure, while his mother and Cécile opened another bottle of champagne. “Although that's not a bad thing in the current circumstances.”

“How can you not see something so obvious?” I asked, brushing my hair, a nightly ritual in which I'd found much comfort from the time I was a little girl. “This screams Sebastian!”

The previous year, during the season, an infamous and clever burglar who called himself Sebastian Capet had plagued London and never been caught by the police. He moved in and out of house after house in search of a most specific bounty: objects previously owned by Marie Antoinette. When he broke into my former home in Berkeley Square, he liberated from Cécile's jewelry case a pair of diamond earrings worn by the ill-fated queen when she was arrested during the revolution. But he left untouched Cécile's hoard of even more valuable pieces. The following morning I had received a note, written in Greek, from the thief. Later, swathed in the robes of a Bedouin, the devious man imposed upon me at a fancy dress ball to confess he'd been taken with me from the moment he climbed in my window and saw me asleep with a copy of Homer's

Odyssey

in my hand. Correctly determining that I was studying Greek (the volume I held was not an English translation), he had delivered to me, over the following weeks, a series of romantic notes written in the ancient language.

“Capet is not the only person in Europe capable of quoting Greek,” Colin said.

“Of course not,” I said. “But you must agree the manner of the theft sounds just like him. Stealing a painting to give it to someone who would appreciate it?” I slipped a lacy dressing gown over my shoulders and pulled it close.

“How does that bear any similarity to a man who was obsessed with owning things that belonged to Marie Antoinette?”

“It's the spirit of it! They both reveal⦔ I paused, looking for the right word. “There's a sense of humor there, a clever focus.”

“Heaven help me. You're taken with another burglar.” He splashed water on his face and scrubbed it clean.

“There is no other burglar. I recognize Sebastian's tone.”

“And you remain on a first-name basis with the charming man. Admit itâfor you, my dear, there will never be another burglar.”

“You're jealous!” I said.

“Hardly,” Colin said. “In fact, I don't object in the least to you investigating the matter further. It might prove an excellent distraction.”

“Did you really have the impression that Inspector Gaudet is competent?”

“He seemed perfectly adequate.” He drew his eyebrows together. “Has he done something to lose your confidence?”

“George wasn't pleased with the way he handled the issue of their intruder.”

“Which is why I suggest you spend as much time as you'd like investigating the matter,” he said.

“And the murdered girl?”

“Sadly, Emily, she is none of our concern.”

5 July 1892

I'm trying my best to tolerate my son's child bride, but the effort would be taxing for a woman of twice my stamina. I realize she's not so young as I imply, but youth, I've always believed, is less about age than experience, and this unfortunate girl has a dearth of it. She's been sadly sheltered for most of her years and perhaps it is unfair of me to expectâor hope forâmore from her. Still, given the way Colin had spoken of her, I'd imagined another sort of lady entirely. I thought he'd be bringing me someone who might prove an interesting sort of companion. Instead, I should perhaps have paid more attention to what her first husband fixated on: her appearance. There may be a reason he went no deeper.

She, of course, views things differently altogether, and is quite proud of her accomplishmentsâimagines herself an independent woman of the world, despite the fact she's the pampered daughter of some useless aristocrat. I don't mean, of course, to insult her father, whom I'm told is a decent man. But I have no use for a social hierarchy that places accidents of birth above merit and achievement. It was my own dear Nicholas's cause, and I've taken it on as mine since his death. Unoriginal, I suppose, to do such a thing. Colin tells me his wife did the same after Ashton diedâsays that she learned Greek and reads Homer and has a propensity for the study of ancient art. Such endeavors must require a certain aptitude and intelligence, but I've yet to see her demonstrate much ability to accomplish anything beyond reading a seemingly endless supply of sensational fiction.

She is taller than I'd expected.

I woke up early the next morning, the first day since we'd arrived in Normandy that I'd come downstairs before luncheon. The combination of my injuries and my mother-in-law's scorn did little to inspire me to action. But today Cécile and I were to visit George and Madeline and examine the note left by their mysterious visitor, and the prospect filled me with excitement. We rode to their château accompanied by a protective footman, following winding roads that meandered through golden fields and into a small, dense wood opening onto a moat whose water was so clear I could see the rocks settled on its bottom. Branches hung heavy from weeping willows along the bank, and on the far side of the water stood a round stone tower with a pointed roof. It could, I suppose, be described as crumbling.

To say the same about the rest of the château wouldn't be entirely correct; George, it seemed, was prone to exaggeration. This was not the refined type of building found in the Loire Valley or at Versailles. It was more fortress than Palace, a true Norman castle, with an imposing keep. We looped around the water and over a rough bridge, then followed the drive along a tall gatehouse fashioned from blocks of stone and golden red bricks, its windows long and narrow. Defensive walls had once enclosed the perimeter, but now all that remained of them were bits and pieces of varying heights, few much taller even than I, most of them covered with a thick growth of ivy or dwarfed by hydrangea bushes. Long rows of boxwoods lined gravel paths in the formal garden, and the flowers, organized neatly in pristine beds, must have been chosen for their scents, as the air was sweet and fragrant.

“The garden is much nicer than the house,” George said, rising from a stone bench and coming towards us, a gentleman with a large, dark moustache at his side. “You'd be wise to stay outside. I can have tea sent to us here.”

“You're doing nothing, sir, but increasing my curiosity about the interior,” I said. “The exterior is lovely.”

“Very medieval,” Cécile said, tipping her black straw hat forward to better shade her eyes from the sun.

“If only I had a catapult,” George said. “We might have some real fun. May I present my friend, Maurice Leblanc from Ãtretat?”

The other man bowed gracefully. “It is a pleasure,” he said as George introduced us.

“Maurice is a writerâdoes stories for every magazine you can think of. Excellent bloke.”

“If you can overlook my failure to complete law school,” Monsieur Leblanc said.

“What sort of things do you write?” I asked.

“I've just finished a piece on France's favorite ghost,” he said.

“Ghost?” I asked.

“I'd hardly be inclined to call any ghost a favorite,” George said.

“But this one isn't full of menace,” Monsieur Leblanc said. “She's sad, lonely, searching for a better mother than the one she had.”

“Do tell,” I said.

“Years ago, early in the century, there lived, in the small port of Grandcamp-les-Bains here in Normandy, a young mother notorious for neglecting her daughter. She let the girl wander through the village at all hours of day and night, didn't send her to school, could hardly be bothered to take care of her.”

“I have heard this story, Monsieur Leblanc,” Cécile said. “And find it hard to believe any woman would treat her own daughter in such a manner.”

“It wasn't always that way,” he said. “But after the woman's husband, a sailor, died in a shipwreck not far from the coast, she could hardly stand the sight of the child. She looked too much like her father, you see, and the grieving mother could not cope. One day, when the girl had begged and begged to be taken on a picnic, they went to Pointe du Hoc, a promontory with spectacular views high above the sea.”

“And of course the mother wasn't watching the girl,” George said.

“Correct,” Monsieur Leblanc said. “And while she was playing, too close to the edge of the cliffs, she slipped and fell to her death. And ever after, there have been stories of peopleâwomenâall through France seeing her. She wanders the country in search of a better mother, one who would look after her properly.”

“Ridiculous,” Cécile said.

George laughed. “Madeline thought she saw her once. Beware, Emily, she may come for you next.”

“I'll keep up my guard,” I said. “But why does she limit her search to France? Are there no decent mothers to be found elsewhere?”

“There might be, but the food wouldn't be nearly so good,” Monsieur Leblanc said, and we all laughed.

A groom appeared from the direction of the barns standing on the opposite side of the grounds from the central building, close to a heavy dovecote built in the style of the nearby tower, all stone, no brick. He took our horses from us as our host led us inside, where Madeline greeted us at the thick, wooden door.

“It's so good of you to come,” she said, kissing us both on the cheeks. “I've asked Cook to make a special fish course. We've mussels, as well, and Iâ”

“They've not come for dinner, darling,” George said, stepping forward and taking his wife's hand. “Just tea, remember? And you asked for

douillons.

”

“Of course,” she said. She spoke with steady resolve, but looked confused.

“No one makes pastry finer than your cook,” Monsieur Leblanc said, his voice firm. “I am full of eager anticipation.”

“Let's go to the library before we eat.” George's words tumbled rapidly from his mouth, as if to redirect the conversation away from his wife's blunder as quickly as possible. “I want to show you the note left by that dreadful man.”

“You are confident it's from a man?” Cécile asked. “Do you not believe a woman might be equally devious?”

“I'd like to believe a woman wouldn't be able to climb into my locked house with a painting on her back. Not, mind you, because I consider the fairer sex incompetent or lacking a propensity for crime. But surely a lady with the strength to accomplish such a thing would look awful in evening dress, don't you think?”

“Not at all,” I said. “I think she'd be elegant beyond measure, and deceive you completely in the ballroom.”

“And would make a most excellent villain. Perhaps I should write about her.” Monsieur Leblanc tilted his head and looked into the distance, as if deep in thought. “Only think of the adventures on which she might embark.”

“I shall not argue with any of you,” George said, leading us through the door into the keep's cavernous hall, its arched ceiling supported by wide columns. The room was overfull of furniture. Around a sturdy table that might have comfortably seated a dozen, eighteen chairs had been set, too close together. Six suits of armor were on display, three separate sitting areas contained settees and more chairs, and on the walls hung a series of tapestries, finely embroidered with scenes of a hunt, the work as fine as that displayed on

The Lady and the Unicorn

set I'd seen in the Cluny museum in Paris.

“How beautiful,” I said, standing close to the first panel.

“They've been in the château since the fifteenth century,” Madeline said. “We think some long-ago grandmother of mine worked on them.”

“This was the center of the original castle,” George said. “Twelfth century. And as you can see, no owner has parted with even a shred of furnishing in the ensuing seven hundred years. The room above this serves as our library, but other than that, we don't use the space for much but storage. A manor house was built later, and I've constructed a passage to connect the two buildings. Will you follow me upstairs?

He led us up a flight of hard stone steps to a much smaller room lined with bookcases. The windows were nearly nonexistent, better suited for shooting a crossbow than looking at the view of the garden below.

“It's a horrible space, I know,” he said. “Terrible light. But then, there are those who say books should be protected from the sun.”

“Magnifique,”

Cécile said. “Functional rather than beautiful. And impenetrable by enemies, I imagine.”

“Which was, no doubt, significant to the original builders. Perhaps I flatter myself, but I myself don't feel in imminent danger of being under siege,” George said. Madeline laughed and kissed him, blushing when she realized we had all seen her.

“You must forgive me,” she said. “I do adore my husband.”

“Something for which you should never apologize,” I said.

Monsieur Leblanc blinked rapidly and shifted his feet in awkward embarrassment. “This would make an excellent writing space. Few distractions.”

“You're welcome to use it any time.” Our host riffled through the drawers of an imposing desk fashioned from heavy ebony, pulled out a note, and handed it to me. “For your reading pleasure.”

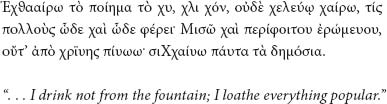

I recognized the handwriting in an instant. There could be no doubt Sebastian had penned it. My Greek, which I'd been studying for nearly three years, was much better now than it had been when I last encountered the clever thief, and I translated the brief phrase at the bottom of the paper:

The passage had to be from the

Greek Anthology,

a collection of ancient epigrams. Sebastian quoted from it frequently in the earlier missives he'd sent me.

“I have missed Monsieur Capet,” Cécile said with a sigh. “He's such a rare breed of gentleman. Refined and focused, clever, but with the sort of dry wit I admire so much. Although after the success of the haystacks, he really ought to consider Monet popular.”

“You know this man who is causing our troubles?” Madeline asked. “Is he dangerous?”

“Dangerous? No, not at all,” I said. “Sebastian might steal everything valuable you own, but he'd never harm you.”

“He'd be more discerning than that,” Cécile said. “He'd only take a selection of your best items.”

This drew a deep laugh from George. “I've half a mind to invite him back, if only I knew how to contact him. We've far too much crammed in most of these rooms, and the attics are a complete disaster. Would he be interested in furniture, do you think?”

“Darling, you know we can't get rid of anything while

Maman

is still alive,” Madeline said. “It would disturb her too much.”

“You shouldn't talk about me as if I'm not here.” All of us but Madeline started at the sound of the voice. An elderly woman stood near the doorway, leaning against the wall. I had no idea where she'd come from or how long she'd been standing there. Her gown was of a rich burgundy silk, beautifully designed, an odd contrast to her coiffureâher white hair hung long and wild down her backâand the strained expression on her face.

“Are you the one they've sent to stop her? She's come again, you know. My daughter's seen her, too,” she said, crossing to George. “We should, I suppose, be introduced.”

Not hesitating in the slightest, George kissed her hand. “George Markham, Madame Breton. I'm Madeline's husband.”

A shadow darkened her face for an instant.

“Bien sûr.”

Her eyelids fluttered. “It's this dark room. Impossible to see anyone until you're directly in front of them. Who is Madeline? Should I be introduced to her?”

“Madeline is your daughter,” George said.

“It's all right,

Maman,

” Madeline said, taking the old woman's hand. “Would you like to have tea with us?”

“Tea?”

George put an arm firmly around her shoulders. “It's time for something to eat. We've

douillons,

and I know how you love pears. Come sit with us. I can read to you after we're done.”

“She doesn't like the books,” she said. “She's crying again and won't stop.”

“Who's crying?” I asked.

George caught my eye and subtly shook his head before leaning in close to her. “We'll go for a little walk and you'll feel better. Then we'll have tea.”

“I can't stand the crying,” she said. “Someone has to make it stop.”

“I'm so sorry,” Madeline said, turning to us as her husband led the old woman from the room. “My mother's not been well for some time. It's nervesâthey plagued my

grand-mère,

too. The doctor tells us there's nothing to be done, and George agrees. He trained as a physician in London, you know, but hasn't had much occasion or need to work. He's the only one able to help her when she has a spell.”

“She's fortunate to have him,” I said. “But how dreadful for her to suffer so.”

“I don't think she has any awareness at all of her condition,” Madeline said. “Sometimes she's lucid, and when she is, she has no idea that she's ever not. Eventually she'll remember nothing. By the time my grandmother died, she didn't recognize any of us. But, come, now, I don't want you all to feel awkward. Let's start our tea.”

Monsieur Leblanc offered her his arm, and we followed them into a narrow corridor lined with tall windows that ran from the keep to a seventeenth-century manor. Stepping into this newer section of the structure was like entering a contemporary Parisian house. Bright yellow silk covered the walls on which stunning paintings hung at regular intervals. There could be no question of the Markhams' love for artâtheir collection ranged from Old Masters to Impressionists, grouped by color rather than style. It was a fascinating method of organization, unlike any I'd before seen. A Fragonard beside a Manet, the two Monet haystacks across from a Vermeer portrait.