Daily Life During The Reformation (2 page)

Read Daily Life During The Reformation Online

Authors: James M. Anderson

1610 | Henri IV of |

1611 | King James Bible |

1618 | Thirty Years’ War |

1620 | Pilgrims arrive |

1621 | Spain’s truce |

1624 | France, Holland, |

1625 | Charles I ascends |

1626 | Siege of La |

1627 | Charles I of |

1628 | La Rochelle falls |

1629 | Parliament |

1630 | Peace made |

1631 | First newspaper |

1633 | Galileo suspected |

1635 | War on Spain |

1636 | War continues |

1640 | Short Parliament |

1641 | Irish Catholics |

1642 | Civil War in England |

1643 | Louis XIV |

1644 | Habsburgs |

1647 | Protestantism |

1648 | Treaty of |

1 - HISTORICAL OVERVIEW OF THE

REFORMATION

Prior

to the Reformation, Europeans believed in God, Christ, saints, and the Bible as

interpreted by the Catholic Church. Any criticism of Catholic views or

tradition, any questioning of its dogma, could elicit dire consequences.

Nevertheless, some men dared to question.

EARLIER DISSENTERS

In the 1300s, John Wycliffe, in England, denounced

corruption in the Catholic Church and questioned its orthodoxy and

compatibility with the Bible. He was posthumously declared a heretic, and by

order of the pope his bones were disinterred, burned, and thrown into the

river.

Later in the century, Jan Hus, in Bohemia, placed emphasis

on the word of the Bible as the sole religious authority. Offered safe conduct

to Constanz to explain his views, he was betrayed and burned there at the

stake. Giralamo Savonarola, from Florence, an Italian Dominican monk, also

spoke out for reform of the Church in the fifteenth century, denouncing the

prevalent corruption and immorality. He and two disciples, still professing

their adherence to Catholicism, were hanged and burned.

The loudest and most energetic opponents of Church abuse

were mostly northern Europeans, such as Erasmus of Rotterdam, who reflected the

spirit of humanism and had a great influence on reformers. At the beginning of

the sixteenth century, he condemned the failings of the Church and society as

well as the religious practices of the ecclesiastical hierarchy that had lost

all resemblance to the apostles they were supposed to represent. Nonetheless,

Erasmus remained true to the Catholic faith.

Some European monarchs, tired of seeing their wealth

drained away by the Vatican, succeeded in their demands for the right to make

their own ecclesiastical appointments, but they still resented the flow of

wealth from their states to Rome in the form of

annates

, Peter’s Pence,

indulgence sales, Church court fines (Church courts shared judicial power with

state courts), income from benefices, fees for bestowing the pallium on

bishops, and perhaps even the money citizens paid to the priest for the many

Masses they often had performed for the sake of loved ones languishing in

purgatory.

They also enviously eyed Church lands and could see the

waste of money tied up in vast Church and monastic holdings that could be freed

for expansion. The peasants, too, who shouldered most of the financial burdens,

expressed similar sentiments in occasional riots.

MARTIN LUTHER

An Augustinian monk, Martin Luther, born in 1483 at

Eisleben, Saxony, in eastern Germany, also found fault with the Church’s

policies.

Luther was infuriated by a fellow Catholic, Johann Tetzel,

a Dominican friar who preached to the people that the purchase of a letter of

indulgence from the pope would ascertain the forgiveness of sins and lessen the

time they or their ancestors would spend in the fires of purgatory. A good

salesman, Tetzel vividly described the torments in purgatory with unrestrained

imagination.

On October 31, 1517, Luther, now a professor at the

University of Wittenberg, nailed 95 theses to the door of the Wittenberg Castle

church, intending for these points, critical of the Church and the pope, to be

subjects of academic debate. The most controversial points centered on the

selling of indulgences and the Church’s policy on purgatory. He was not trying

to create a new religious movement.

Luther sent a copy of the theses to Archbishop Albrecht of

Mainz, Tetzel’s superior, requesting the Archbishop put a stop to Tetzel’s

high-pressure sales of indulgences. He also sent copies to friends. There were

direct references to reform in the document: thesis 86, for example, referring

to money collected from indulgences supposed to help fund the construction of

Saint Peter’s Cathedral in Rome, asked “Why does not the pope, whose wealth is

to-day greater than the riches of the richest, build just this one church of

St. Peter with his own money, rather than with the money of poor believers?”

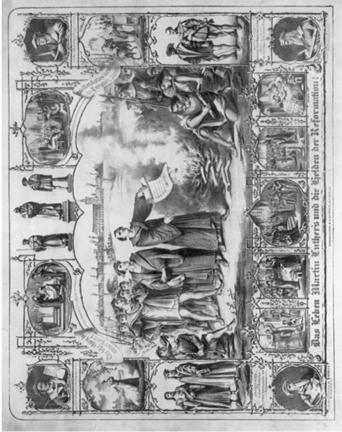

Luther directs the posting of

his 95 Theses, protesting against the sale of indulgences, to the door of the

Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany, 1830.

Archbishop Albrecht, who held three benefices (contrary to

canon law), acted as chief commissary for the disposal of money from

indulgences. Pope Leo X had granted him a dispensation for the sum of 24,000

ducats that Albrecht raised by borrowing from private bankers. To pay off his

debt, half of the income from indulgences was to go to Albrecht and his bankers

and the other half to the pope. How much Luther knew of the secret and shady

deals at the Vatican may never be known. The fall in revenues worried Albrecht,

and he reported Luther’s interference and questionable orthodoxy to the pope

who at first considered the theses the work of a drunken German. Luther wrote

to the pope that faith alone, not priests, was the way to salvation. Such an

opinion was anathema to the Catholic Church and resulted in his condemnation.

In August 1518, Luther was summoned to Rome to be examined

on his teachings, but his territorial ruler, Elector Frederick III of Saxony,

knowing the journey would not be safe, intervened on his behalf and supported

Luther’s wish to have an inquiry conducted in Germany since he felt it was his

responsibility to ensure his subject was treated fairly. After seeing what had

befallen Jan Hus, who could be sure of what would happen in Rome?

The pope agreed to Frederick’s demands because he needed

German financial support for a military campaign against the Ottoman Empire,

whose forces were poised to march on central Europe, and because Frederick was

one of the seven electors who would choose the successor of the ailing Emperor

Maximilian. The Papacy had a crucial interest in the outcome of this election,

hoping for a dedicated Roman Catholic.

Luther was summoned to the southern German city of Augsburg

to appear before an imperial Diet in October 1518, where he met with Cardinal

Cajetan, who demanded that the monk repudiate his beliefs. Luther refused, and

nothing was accomplished.

By the end of the same year, Luther came to some new

conclusions regarding the Christian notion of salvation. In the view of the Church,

good works were pleasing to God and aided in the process leading to salvation.

Luther rejected this, asserting that people can contribute nothing to their

salvation, which is fully a work of divine grace. His insight that faith alone

provided the road to salvation came to him while meditating on the words of

Saint Paul. For Luther, neither indulgences nor good works played any part in

this. Man could not buy his way into Heaven.

The controversy prompted Johann Eck, a Catholic theologian,

to set up a public debate with Luther in Leipzig in July 1519. Eck attacked

Luther, and the debate over Church authority grew fierce. Eck demanded to know

how God could let the Church go astray. Luther responded by pointing out that

the Greek Orthodox Church did not acknowledge Rome; hence it had already gone

astray. Luther was then charged with taking the point of view of the heretics,

Wycliffe and Hus. He also demanded to know if Luther considered the Council of

Constanz (which had condemned Hus) had made a bad judgment, and Luther affirmed

that councils could err, a heretical statement in itself.

Arguments on other matters such as purgatory and penance

continued for several more days. Convinced that through Christ alone lay the

road to redemption; Luther asserted that he recognized only the sole authority

of scripture. After Luther departed Leipzig, a war of books and pamphlets by

both factions ensued.

Luther’s writings in 1520 included his belief in the

priesthood of all believers, and he tried to convince secular rulers to use

their God-given authority to rid the Church of immoral prelates including

popes, cardinals, and bishops.

Attacks on the holy sacraments followed. A Papal Bull,

issued by Pope Leo X on June 15, 1520, gave Luther 60 days to repent.

On December 10, 1520, sympathetic Wittenberg students lit a

bonfire burning up books of canon law as well as others written by Luther’s

enemies. Luther himself threw a copy of the pope’s Bull into the flames.

Another Papal Bull issued on January 3, 1521 excommunicated Luther and gave

orders to burn all his writings. The aging Holy Roman emperor, Maximilian I,

had meanwhile died in 1519, and Charles V, a rigid Catholic, was now at the

helm of the Empire.