Cutting for Stone (47 page)

Authors: Abraham Verghese

Tags: #Electronic Books, #Brothers, #Literary, #N.Y.), #Orphans, #Ethiopia, #Fathers and Sons, #2009, #Medical, #Physicians, #Bronx (New York, #Twins, #Sagas, #Fiction

The less said about my cold, bumpy, seven-hour ride to Dessie, the better. After a night in a Dessie warehouse, where I slept on a regular bed, and a second night where we rested in Mekele, on the third day of out northern journey we reached Asmara, the heart of Eritrea. The city Genet had loved so much was under occupation. The Ethiopian army was visible in force, tanks and armored cars parked at key junctions, checkpoints everywhere. We were never searched, since the driver's papers showed the tires we carried were to supply the Ethiopian army.

I was taken to a safe house, a cozy cottage surrounded by bougainvil-lea, where I was to wait until we could make the trek out of Asmara and into the countryside. The furniture was just a mattress on the living room floor. I couldn't venture out to the garden. I thought I'd be in the safe house for a night or two, but the wait stretched out to two weeks. My Eritrean guide, Luke, brought me food once a day. He was younger than me, a fellow of few words, a college student in Addis before he went underground. He suggested I walk as much as I could in the house to strengthen my legs. “These are the wheels of the EPLF,” he said, smiling, tapping his thighs.

There were two surprises in my meager luggage. What I thought was a cardboard base at the bottom of the Air India bag that Hema packed was instead a framed picture. It was the print of St. Teresa that Sister Mary Joseph Praise had put up in the autoclave room. Hema's note taped to the glass explained:

Ghosh had this framed in the last month of his life. In his will he said that if you ever left the country, he wanted this picture to go with you. Marion, since I can t go with you, may my Ghosh, Sister Mary, and St. Teresa all watch over you.

I caressed the frame, which Ghosh's hands must have touched. I wondered why he'd taken so much trouble, but I was pleased. It was my talisman for protection. I had not said good-bye to her in the autoclave room, and it turned out I didn't need to, because she was coming with me.

The second surprise was the book under Shiva's precious

Gray's Anatomy.

It was Thomas Stone's textbook,

The Expedient Operator: A Short Practice of Tropical Surgery.

I'd never known such a book existed. (Later I learned that it went out of print a few years after our birth.) I turned the pages, curious, wondering why I'd never seen this before and how it came to be in Shiva's possession. And then, suddenly, there he was in a photograph that occupied three-fourths of the page, staring out at me, a faint smile on his lips: Thomas Stone, MBBS, FRCS. I had to close the book. I rose and got some water, took my time. I wanted to compose myself and look at him on my own terms. When I opened the page again, I noticed the fingers, nine of them, instead of ten. I had to admit the similarity to Shiva and therefore to me. It was in the deep-set eyes, in the gaze. Our jaws were not as square as his and our foreheads were broader. I wondered why Shiva had put it in my hands.

The book looked brand-new, as if it had hardly been opened. A bookmark placed on the copyright page said, “Compliments of the Publisher.” The bookmark had been pressed between the pages for so long that when I peeled it off a pale rectangular outline remained.

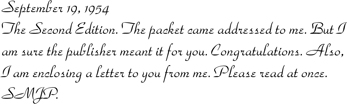

On the back of the bookmark was written:

My mother had penned this note a day before our birth and her death. Her clear writing, the even letters, retained a schoolgirl's innocence. How long had Shiva posessed the book and bookmark? Why give it to me? Was it so that I'd have something from my mother?

To get in shape, I'd pace around the house, hauling the bag with books on my shoulder. I read Stone's textbook during those two weeks. At first I resisted it, telling myself it was dated. But he had a way of conveying his surgical experience in the context of scientific principles that made it quite readable. I studied the bookmark often, rereading my mother's words. What was in the letter she had left for Stone? What would she have been saying to him just one day before we, her identical twin boys, would arrive? I copied her writing, imitating the loops.

One day when Luke brought my food, he said we'd leave that night. I packed one last time. The two books had to go with me; I couldn't abandon either one, though my Air India bag was still very heavy.

We set out after curfew. “That's why we waited,” Luke said, pointing skyward. “When there's no moon it is safer.”

He led me down narrow paths between houses, and then along irrigation ditches, and soon we were away from the residential areas. We crossed fields in the pitch-dark. I sensed hills in the distance. Within an hour, my shoulder hurt from the bag, even though I positioned it in different ways. Luke insisted on transferring some items from my bag to his knapsack. He looked shocked at the sight of the books, but said nothing. He took the

Gray's.

We walked for hours, stopping only once. At last, we were in the foothills, climbing. At four-thirty in the morning, we heard a soft whistle. We met up with a troop of eleven fighters. They greeted us in their trademark fashion: shaking hands while bumping shoulders back and forth, saying,

“Kamela-hai”

or “Salaam.” There were four women, sporting Afros just like the men. I was shocked to recognize one of the fighters: it was the firebrand, the student with the bovine eyes whom I had encountered in Genet's hostel room. On that occasion hed stormed out contemptuously. Now, recognizing me, he sported a lopsided grin. He shook my hand with both his. His name was Tsahai.

The fighters were exhausted, but uncomplaining, their legs white with dust. They carried a heavy gun which they had dismantled into several large pieces.

Tsahai brought something over to me. “High-protein field bread,” he said. It was a ration which was of the fighters’ own invention, but it tasted like cardboard. He rubbed his right knee as he spoke, and it looked to me as if it was swollen with fluid. If it was sore, he said nothing about it.

We avoided the topic of Genet. Instead he described how earlier that night they'd ambushed an Ethiopian army convoy as it tried a rare night patrol. “Their soldiers are scared of the dark. They don't want to fight and they don't want to be here. Morale is terrible. When we shot the lead vehicle, the soldiers jumped out, forgetting to shoot, just running for cover. We had the high ground on both sides. Right away they screamed that they were surrendering, even though their officer was ordering them to keep fighting. We took their uniforms and sent them on foot back to the garrison.”

Tsahai and his comrades had siphoned gas from the trucks, then hid the one working vehicle in the bush, stuffed with uniforms, ammunition, and weapons to be retrieved at another time. The real prize was the heavy gun and shells which they brought with them, everything carried on foot.

WE SET OFF

after fifteen minutes. Before daybreak we reached a well-hidden, tiny bunker carved out of the side of a hill. I didn't think I was capable of walking as far as I had. It helped that my fellow walkers carried five times my load without complaint.

Luke and I stayed in the bunker. The others hurried on to a forward position, risking daylight and being spotted by the roaming MiG fighters because there was some urgency to reassemble the gun.

I slept until Luke woke me. My legs felt as if a wall had collapsed on them. “Take this,” he said, giving me two pills and a tin mug of tea. “It's our own painkiller, paracetamol, manufactured in our pharmacy.”

I was too tired to do anything but swallow. He made me eat some more of the bread, and I slept again. I awoke with less pain, but so stiff I could hardly get off the floor. I took two more of the paracetamol pills.

Five fighters arrived to escort us onward when it turned dark. One of them had a partially withered leg: polio, I knew. Seeing his swinging, awkward gait, his gun serving as a counterbalance, made it impossible for me to think of my own discomfort.

The second march was half as long as the first, and gradually my legs loosened. We arrived long before dawn at some scruffy hills. A narrow trail led to a cave, its entrance completely hidden by brush and by natural rock. Wooden logs framed the opening. A steep wooden ramp went down to more rooms, deep within. The trail on the outside led to other caves up and down the hill, all the openings cleverly concealed.

I was taken inside to a stall. I removed my shoes, and fell asleep on a straw pallet. It felt luxurious. I slept till late afternoon. Luke walked me around. I was stiff again, but he seemed fine. The base was empty of fighters because of a major operation going on elsewhere.

I suppose I should have admired these fighters, who could flit through the dust like sandflies. I should've admired their resourcefulness, their ability to manufacture their own intravenous fluid, their own sulfa, penicillin, and paracetamol tablets stamped out by a handpress. Hidden in these caves and invisible from the air or ground was an operating theater, a prosthetic limb center, hospital wards, and a school. The degree of sophistication in those surroundings was even more impressive for being so spartan. The quiet discipline, the recognition that the tasks of cooking, caring for children, sweeping the floors were as important as any other, convinced me that they would one day prevail and have their freedom.

I watched a fighter relaxing outside the bunker. The sun filtering through the acacia tree formed a changing mosaic of light on her face and on the rifle across her lap. She hummed to herself as she scanned the skies with binoculars, looking for MiGs, which were flown by the Rus sian or Cuban “advisers” to Ethiopia. America had long supported the Emperor, but it withdrew its support of Sergeant-President Mengistu's regime, halting weapons and parts sales. The Eastern Bloc stepped in to fill the void.

The fighter, who was about our age, reminded me of Genet in the way she arranged her limbs, in the ease with which she occupied her body. Despite the lethal weapon in her hand, her movements were delicate. She wore no makeup, and her feet were dusty and callous. Seeing her I was grateful for one thing: my Genet dream was gone forever and good riddance. Id been so stupid to sustain a one-sided fantasy for so long. The honeymoon in Udaipur, our own little bungalow at Missing, raising our babies, setting off to the hospital in the morning, doctors working side by side … It would never happen. I never wanted to see her again. And I probably never would. She was surely in Khartoum, still basking in the glory of her daring operation. There was no going back to Addis for her either. Soon she would join these fighters, live in these bunkers, and fight alongside them. I hoped I would be long gone by then. I resented having to be in their camp at all, even more having to turn to her comrades for help.

That night I woke to the sounds of MiGs overhead and bombs dropping far away, but close enough for us to hear the rumble. Also the fainter thuds of artillery. No lights were allowed anywhere near the mouth of the cave.

Luke said that a massive raid had just been completed on a weapons and fuel depot. It had included Tsahai and the group of fighters we met on the first night. They had penetrated using a stolen army truck. Once inside, they set charges, but their comrades outside had been surprised by a reinforcement convoy that attacked them from the rear. It had not gone exactly as planned. Nine guerrillas including Tsahai were dead and many more wounded. The Ethiopians’ losses were much larger and the fuel depot partially destroyed. Our casualties would arrive at the cave by early morning.

I woke to voices, the activity and urgency unmistakable. I heard moans and sharp cries of pain. Luke took me to the surgical ward.

“Hello, Marion,” a voice said. I turned to see Solomon, whod been my senior in medical school. Hed gone underground as soon as he finished his internship. I remembered him as a chubby, well-fed intern. The man before me had hollow cheeks and was as lean as a stick.

I followed Solomon, stooping down in a low-ceilinged tunnel where stretchers were arranged in pairs on the floor, triaged so that those most in need of surgery were closest to the operating theater at the end of the tunnel. The entrance to the theater was a cloth curtain.