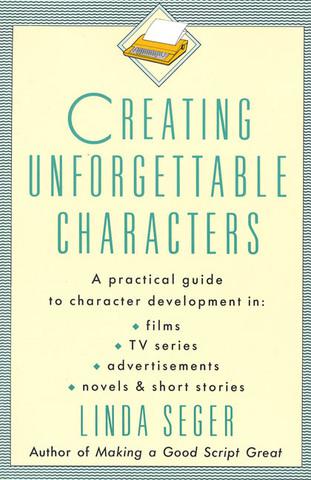

Creating Unforgettable Characters

Read Creating Unforgettable Characters Online

Authors: Linda Seger

A number of years ago, I was called in by a television producer who was confronting a character problem in one of her scripts. A well-known, respected actor was already cast in the role, but the part was limited in its scope. During the consulting session, we brainstormed further emotional layering, other dimensions to his character, and potential transformations. Later, the actor was nominated for an Emmy for his performance.

Some months later, I was asked to consult with some producers of a series that was in trouble. Ratings were low, the network was threatening to cancel. Although the acting was excellent, and the broad strokes of the characters were well drawn, there was little character expansion. In an evening seminar, we brainstormed potential conflicts, story issues that could expand character dimensionality, dynamic relationships that were already part of the series but had been unexplored, and reasons why audiences might want to be involved with these characters week after week. The producers were enthused, and set about to turn the show around. But it was too late. The network had already decided to cancel. Since then, the multitalented and popular star has not yet found another series, in spite of a number of successes in the past.

In both these situations, character was the key to a workable story. Great characters are essential if you want to create great fiction. If the characters don't work, the story and theme will not be enough to involve audiences and readers. Think of the memorable characters in the novels of

Gone With the Wind, To Kill a Mockingbird, Jane Eyre, Tom Jones;

or from the plays

Amadeus, Les Liaisons Dangereuses, The Glass Menagerie

; the films

Casablanca, Annie Hall, Citizen Kane;

the television series "I Love Lucy," "All in the Family," "The Honey-mooners." Even action-adventure films such as

48 HRS., Lethal Weapon,

and

Die Hard,

and horror films such as

Nightmare on Elm Street

credit their success to strong, well-drawn characters.

Creating unforgettable characters is a process. Although some writers say that it can't be taught, as a script consultant I've learned that there are processes and concepts that can effectively improve characters. By talking to many critically acclaimed writers, I've learned techniques and methods that great writers use to create great characters.

I also know that the problems that writers confront are confronted as well by producers, directors, executives, and actors. These are the people who must define the character problem, ask the right questions, and point the way to workable solutions.

The concepts within this book relate to the creation of all fiction characters and are based on the principles I've discovered as a drama professor, a theatre director, and, for the last ten years, a script consultant. For this book, I've interviewed over thirty writers who have articulated and affirmed these concepts; these include novelists and writers for film, television, plays, and advertising. Since my business focuses on screenplays, most of the examples are from film and television. Most of the literary examples come from novels and plays that have been made into films, since either the film or the novel will probably be known to most readers. During my conversations with novelists, they affirmed that all the character concepts I've discussed in relation to film and television are also applicable to the novel.

Since my previous book,

Making a Good Script Great,

deals with character in relation to story and structure, I have chosen not to repeat that information. Instead I will concentrate on the process of creating well-rounded individual characters, and characters in relationship. If you are a new writer, understanding these processes can help you know where to turn when inspiration seems to fail. If you're an experienced writer, you may have occasionally found that one of your characters just doesn't work. Reviewing these processes can help you understand what you do instinctively.

Character is created through a combination of knowledge and imagination. This book is designed to stimulate your creative process, and to take you through a process that will culminate in strong, dimensional, unforgettable characters.

Some time ago, one of my writing clients came to me with a terrific concept for a script. She had worked and reworked the script for over a year. Her agent was excited and eagerly awaiting this new story.

Although she had been told that some of her scripts weren't strong enough for the American commercial market, this one was exciting and tough. It was the kind of story that many producers called "high concept"—with a strong hook and unique approach to the story, a clear conflict and identifiable characters.

Her first film had just been completed, and she was counting on this script to break new ground. She had to finish quickly—but the characters weren't working. She was absolutely stuck.

When I analyzed the script, I realized that she didn't know enough about the context—about the world of the characters. A number of scenes took place in a center for the homeless. Although she had spent some time serving soup at the center, and talking to the homeless, she had never experienced sleeping there or being on the streets. As a result, details and emotions were missing. It was clear that there was only one way that she could break through the character problems—she had to return to research.

The first step in the creation of any character is research. Since most writing is a personal exploration into new territory, it demands some research to make sure that the character and context make sense and ring true.

Many writers love the research process. They describe it as an adventure, an exploration, an opportunity to learn about different worlds and different people. They love seeing characters come to life after spending several days learning more about their world. When their research proves something they intuitively knew, they're overjoyed. Every new insight gained through research makes them feel they have made giant strides in creating an exciting character.

Others find research intimidating, and the most difficult part of the job. Many writers resist it, and resent spending hours making phone calls or foraging for information in the library. Research can be frustrating and time-consuming. You can go down a great many blind alleys before you accomplish a thing. You may not know how to begin to research a specific character point. But research is the first step in the process of creating a character.

The depth of a character has been compared to an iceberg. The audience or reader only sees the tip of the writer's work— perhaps only 10 percent of everything the writer knows about the character. The writer needs to trust that all this work deepens the character, even if much of this information never appears directly in the script.

When do you need to research? Consider for a moment: You're writing a novel. Everyone who has read it agrees that your protagonist, a thirty-seven-year-old white male, has a fascinating personality, but there are certain motivations they don't understand. You decide you need to learn more about the inner workings of your character. A friend suggests you read

Seasons of a Man's Life

by Daniel Levinson, about the male mid-life crisis. You also arrange to sit in on a group of men in analysis. Through this research, you hope to learn what happens to men in the mid-life transition, and how it motivates their behavior.

Or, you've just finished your script, but the supporting character of the black lawyer doesn't seem as fleshed out as the others. You contact the NAACP to see if they know a black lawyer who might be willing to talk to you. You need to gain an insight into ways the ethnic background will affect this particular character in this particular occupation.

Or, you've been assigned to write a film about Lewis and Clark. You're smart—you ask the studio for research money, transportation expenses, and eight months' time. You know you will need to understand the experience of the journey, and how the period will affect the characters and the dialogue.

GENERAL VS. SPECIFIC RESEARCH

Where to start? First, understand that you're never starting from scratch. You have been doing research your whole life, so there is a great deal of material to draw upon.

You are doing what's called

general research

all the time. It's the observation—the noticing—that becomes the basis of character. You're probably a natural people-watcher. You observe how people walk, what they do, what they wear, the rhythms of their speech, even their thought patterns.

If you have another profession besides writing—perhaps medicine, or real estate, or teaching history—all the material you absorb within those jobs can be applied when you write a script for a doctor series, or a story about the real estate profession, or a novel or screenplay that takes place in medieval England.