Crows & Cards (7 page)

Authors: Joseph Helgerson

Meantime, I kept myself busy watching Dr. Buffalo Hilly up on the painted wagon's seat. He had to be the one driving it. Who else would be dressed up like a cavalry captain? And with a purple plume sticking out of his hat too. He was playing some kind of musical box that I later heard called an accordion.

Did I mention he had a camel pulling that wagon?

I recognized it straight off from a picture in my ma's dictionary, and that dromedary wasn't the end of the amazements either. No sir, what brought up the rear didn't simmer things down one bit, for tagging along behind that painted wagon was an Indian princess. Had to be. She was leading a white-faced pony that was carrying a full-grown Indian chief whose war bonnet was long enough to drag feathers across the ground.

The medicine wagon creaked on past, gathering up the lame and achy and pockmarked as it went, but the Indian princess stopped directly in front of the

Rose Melinda.

Leaving the pony, she worked her way down to the shoreline in front of me. She couldn't have been much beyond fifteen feet distant and had the brownest, swimmingest eyes I'd ever run across. They beat horse eyes and cow eyes all flat. In fact, most every other pair of eyes I've seen before or since weren't nothing but washable buttons compared to 'em.

And then she blinked!

I flinched.

That made her smile a flicker, if that long, before turning and warbling something in Indian lingo to the chief.

Up to then the chief had been staring straight ahead, but now he turned toward the

Rose Melinda

and gazed at me. You could tell in a flash he was blind, as both his eyes were snowier than a blizzard, not that it mattered. I sure enough felt as though he was seeing parts of me never before seen under the sun, parts I didn't even know I had.

After a bit, he raised his right hand, kind of stern-like, to show me his palm. I'd heard that's how Indian folks say hello, so I raised my hand back.

The instant I done it, the chief smiled possum-wide and dropped his arm! Now how'd he know to do that? The princess sure had never said a word to tip him off. What's wilder, my hand flopped down in the same breath, without any marching orders from me. Why, I didn't feel much different from some puppet on a string, which spooked me considerable. To get a good deep breath in me, I had to step back from the railing.

"Looks like old Chief Standing Tenbears has cards on his mind," Chilly said, satisfied-like.

"Y-you know him?" I stuttered.

"More than I care to admit," Chilly mumbled.

"He lives here?" St. Louis appeared to have everything.

"So long as I still got his medicine bundle, he does. I don't imagine he can go home without it. That thing means more to him than life itself."

"How'd you get ahold of such a thing as that?"

"The chief likes to imagine himself a poker player. Matter of fact, he's got a solid gold crown you're going to help me win."

"I am?" I edged back to the railing for a peek, but the princess had already returned to the chief and moved on.

"Oh yes," Chilly predicted. "You and that telegraph I told you of."

We stood there quite some while longer as Chilly explained that a little ways back the chief had wagered the most valuable thing he owned against a sizable pot of cash. Chilly took the bet, assuming that the chief's prize possession was a gold crown he was supposed to tote around.

"Wasn't the case though," Chilly muttered. "When that scamp lost, he trotted out a moth-eaten old medicine bundle, claiming it was what he owed me. There was tears pouring down his cheeks—that's how shook up he was 'bout parting with it."

Seeing how much that ratty bundle meant to the old man, Chilly had offered to take the chief's gold crown instead, but that wouldn't do. The princess declared that above everything else her father was a man of his word. He'd wagered his most valuable possession and that meant his medicine bundle, which was worth a half-dozen gold crowns so far as he was concerned.

"Couldn't budge him on it either," Chilly complained. "But it ain't no matter. I'm still going to get that gold crown or my name's not Charles Ambrosius Larpenteur—the Third."

Hearing his whole name roll off his tongue like quicksilver gave me goose flesh. I, for one, wouldn't have bet against him. The freight wagons and Conestogas rolling by on the levee didn't stop to call him on it either. Even a policeman strolling past bit his tongue, though he did seem to keep a wary eye on us.

Not till the policeman was good and gone did Chilly give the sky one last peek and decide that the coast looked about as clear as it was likely to get. We headed ashore, jumping aboard a coach that was leaving the corner of Locust and Second streets for the south part of St. Louis. That suited me about perfect, since my Uncle Seth's tanning yard lay to the north end of town.

For a few blocks the coach clacked over cobblestones, which took some getting used to after the muddy, rutted lanes back home. The storefronts along the way were mostly stone or brick and right smart looking. Off to one side I saw a hotel so fancy, it flew its own flags up top. Down another street rose up a domed courthouse, though I didn't know what a dome was till I asked. Chilly explained that to me as if I was some kind of chucklehead, which didn't rub me too wrong, not busy as I was taking in the sights. There were tobacco warehouses and stove works and a church with a spire so tall that its clapboards must have got their white from rubbing against the moon. I saw a game of ten pin and noticed that most everyone who could afford the luxury was puffing cigars. The smoke must have scared off some of the odors ranging around.

Any kind of critter capable of pulling something was on duty. I even saw a dog harnessed to a toy wagon full of coal chunks. The ragamuff guiding that dog was a lippy little thing, sticking his tongue out at me as we rolled by. The brat's ma caught him at it and right there in public took a broom to his bottom. He commenced to weeping and wailing, but I didn't feel too sorry for him. Unlike some of us, didn't he still have a ma standing beside him?

The boy's coal must have tumbled off one of the full-sized wagons hauling it up and down the street. And the drivers of those bigger outfits certainly had a la-di-da way of cracking their whips. Then too, there were gents and ladies riding in fancy rigs and riffraff just woke up from their beds of straw. Most every block had one or more grog shops or beer houses or saloons or coffeehouses that appeared to sell drinks strong enough to rattle your teeth, if you had any.

Pretty soon the pavement piddled out and dirt took over. There were holes and ruts that must have seemed as deep as small canyons to the coach's horses, easy as they spooked. The streets narrowed up and went all crooked as everything got older, and storefronts gave way to houses that appeared thrown together out of wood and spit. Old ladies on caved front steps sang out, "

Bonjour.

" Chilly told me that was French for "Mind your own business." I figured maybe he was funning me, friendly as those ladies seemed.

Finally the coach creaked to a halt and the driver called out, "End of the line," which meant we had to hoof it from there, with me lugging Chilly's carpetbag along with my poke and boots. There wasn't even any discussion about my being a pack mule. Chilly just dropped his bag on my toes and headed off without checking to see how I was keeping up. Not that I minded. Eager as I was to see where we were headed, I'd have tried to carry Chilly too, if he'd asked me. We kept moving away from the river till we nearly ran out of town, picking our way from one patch of shade to the next as if hiding from something, though surprising us would have been a task, what with the way Chilly kept a weather eye on everything, including the sky. The only man I ever saw watch the heavens any closer was my pa, who foretold rain, sleet, and hail regular as clockwork.

At last we pulled up to a rambling, old two-story house that was knocked out of dark timbers. There was a sign hanging over its front door that had a red, spouting whale painted on it. I wished I could have shown off that sign to my littlest brother, Lester, who was all the time wild about whales. Being but three, he couldn't hold chalk proper yet so was forever pestering me to copy the whale picture from Ma's dictionary for him. Thinking of that gave me a pang. Anyway, somebody had peppered the whale on that sign pretty lively with shot, but it kept right on swimming along, which I figured I better do too.

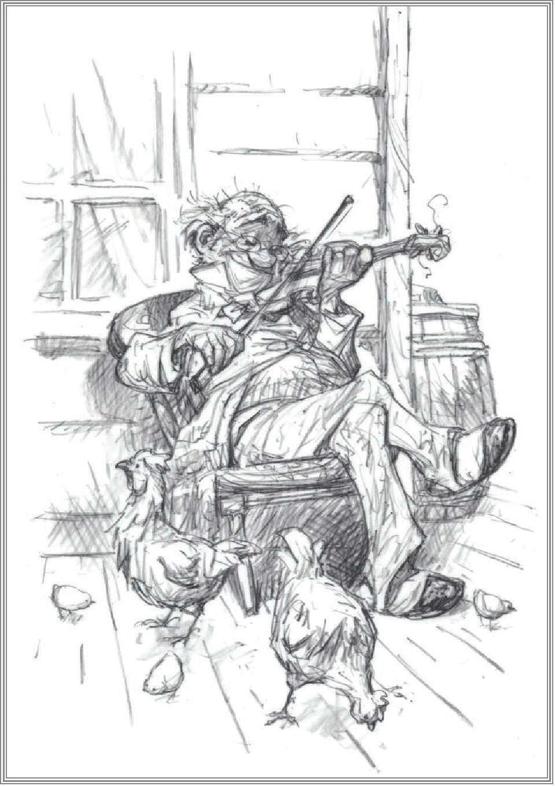

To one side of the house was a tipsy balcony where a man sat on a split-bottom chair playing something weepy and mournful on a violin. He didn't hold it like some country fiddler but had it tucked under his clean-shaven chin. Dignified as he sat there, you didn't hardly notice the pair of Shanghai chickens pecking around his boots. More what caught your eye was the way he pursed his lips, as if tasting the music, and how what few wisps of hair he had left fell across his smudged eyeglasses whenever he leaned forward to tease out a high note.

"That fool's the Professor," Chilly informed me. "Don't get any notions about those hens of his. They follow him everywhere, worse than family."

Without any further to-do, Chilly pushed on up the front steps and into the house, which had itself quite a stock of glass in its windows and real fetching calico stretched over the panes that had gone missing. There were several dogs howling out back who seemed to be objecting to the piano playing going on inside the place. I couldn't see how the Professor's violin would have set 'em off, but that piano playing was another breed of music entirely. Whoever was pounding on those keys knew no mercy.

"This here's Goose Nedeau's place," Chilly said, "or at least half of it is. The other half come into my hands a while back over a matter of some deuces. It's where we'll be holing up. There's only but two things you got to remember if you're going to get along with Goose."

"What's those, sir?" I had to speak up loud to be heard above the dogs and piano and violin.

"Don't talk harsh of his piano playing and keep your hands off that whale sign. It was handed down from Goose's father, all the way from the isle of Nantucket."

I vowed I'd do my best.

CHAPTER NINE

T

HE NEXT FEW DAYS FLASHED BY

quicker than a jenny wren. Chilly and me shared a room on the second floor of the house, which turned out was really an inn. He got the bed, leaving me any spot I wanted on the floor. I didn't get so much as a corn-shuck tick to curl up on, just an old patched-up throw like the one the hounds bedded down on back home. At night, when I rolled up in that ripped old blanket, the back of my ears went all lonesome on me, 'cause of course that's where Pa used to scratch his dogs if they nuzzled his leg.

One corner of the room had a wardrobe, where Chilly piled all his truck, including everything from vests with handpainted tigers on 'em to an alligator hide. Winnings, he called 'em. Over in another corner stood a wood stump with a fancy silver box resting atop it. When late afternoon sun hit that hammered silver, it hurt just to glance that way. And that was only the beginning of what I could tell you about that little treasure chest. It was where he stashed good-luck pieces won off other gamblers. That thing was jam-packed with the most unlikely collection of stuff imaginable: a blue-jay feather, a brass ring, a tear-soaked letter. One misguided fella had contributed a walrus tusk, or at least that's what Chilly called it. He let me heft it in my hand while advising, "Let that be a lesson to you. There wasn't a thing under the sun going to help that fool fill an inside straight. Not while I was dealing."

I'd have to say that nothing pleased Chilly more than dropping some poor gambler's last hope inside that box and closing the lid.

The room also had a washbasin, and it fell to me to keep fresh water in it. Hanging above the basin was a gold-framed mirror that Chilly used for shaving. If you glanced in the mirror just right, from the side, you could see that atop the wardrobe sat a deerskin wrapped around something bulgy. That was the Indian chief's medicine bundle, I guessed. I kept at least as far away from it as I did from the gator hide.