Crossing the Borders of Time (66 page)

It was too late for us to be included on that year’s list of official invitees whose travel expenses the city would reimburse. But Mom wondered if it might be possible for us to go there on our own and meet the other visitors, conceivably including former friends of hers. She broached the subject when I was in New Jersey with Dan and our two children—Zach then four, and Ariel two—and my husband encouraged me to go along with Gary and my parents for what was bound to prove a meaningful experience as we traveled to the scenes of long-familiar stories.

Enticing as the prospect was, it seemed poignantly ironic that the most ambitious family adventure we had ever undertaken was one that now required my father to travel with a wheelchair. Except for visits to the zoo with his two adored grandchildren—whom he encouraged to call him “Grumps” in keeping with his flinty personality—he rarely submitted to what he viewed as a public admission of disability and hence refused to invest in a better model than the flimsy castoff he obtained from the local ambulance department. Still, how ill suited it would prove for days spent rolling over knobby European cobblestones was an aspect of trip planning none of us considered. Also not discussed, but ultimately touching, was his unselfish generosity in agreeing to a difficult expedition solely to please Mom, who would not have gone without him.

Better foresight was involved in my arranging to write about our journey for

The New York Times

. The paper assigned photographers in Germany and France to join us on the way, and later, when the article appeared, it surprised me by provoking the largest reader response of my career. Calls and letters poured in from strangers across the country telling of similar experiences, either in the war or on subsequent visits back to places they’d escaped. Of even greater interest, other former refugees who recognized Janine as someone they had known in Europe or in Cuba now reached out to get in touch with her again. Yet most significant for all of us, the newspaper assignment helped to turn the trip into a purposeful mission of fact-finding and rediscovery. It became my impetus for initiating meetings and explorations we might otherwise have missed, had I not been wearing the persona of a reporter bent upon historical research, albeit personal in focus.

So it was in Freiburg that Mom and I were invited to the sixteenth-century Rathaus or city hall for an interview with Mayor Dr. Rolf Böhme and sat in his office with the ghost of my grandfather. Sigmar would have been amazed and overcome with German pride to see us welcomed with honor in the very town that had placed his name on an official boycott list, forced him to relinquish all his assets, and driven him to flee with nothing. A liberal-minded Social Democrat, Mayor Böhme had been instrumental in organizing the visits of Jewish former citizens as part of a broad campaign of reconciliation that included a student exchange program with Israel and the construction of a synagogue on land donated by the city near its glorious cathedral.

The groundbreaking in 1985 coincided with the first reunion, and the new synagogue, replacing the nineteenth-century original destroyed on

Kristallnacht

, opened in 1987. The mayor pointed out that it incorporates a Freiburg

Bächle

in its design, with one of the city’s small canals running across the sidewalk to the temple, where Germany’s waters bubble up at the open core of a large steel Star of David. In what remained a mystery, he noted, in 1938 the old synagogue’s elaborately carved wooden doors were thankfully removed, saved from the fires of

Kristallnacht

and hidden—along with the Torah’s silver breastplate—in the basement of a city museum. When the modern synagogue was erected, the original doors were brought back into use for a new Jewish population then numbering about one hundred, the vast majority not German, but people who had moved to Freiburg since the war from Russia or Eastern Europe.

Only five members of Freiburg’s original Jewish community returned from the concentration camps after they were liberated, he said. Rare, too, were those who managed somehow to escape the Nazis and then came back to live in Freiburg when the horror ended. Mayor Böhme told us he was well aware that older citizens now felt shame in facing former Jewish neighbors who visited the city in its organized reunions. He was nonetheless committed to what he called a civic responsibility of confronting and atoning for the past. From his desk, he picked up a nondescript black rock that he had taken from Auschwitz a decade earlier, and he slammed it against his blotter with a thud so resolute it had the impact of a vow. “This stone is from the spot where Jews were selected for life and death,” he said, as heavily as if the stone encapsulated the weight of Nazi guilt. “It is always here … to be conscious … never again.”

Awed by the unanticipated beauty of Mother’s birthplace and its backdrop of deep green mountains, we marveled at the picturesque medieval buildings in the historic core of town that were flattened by British bombers in 1944 and then meticulously restored—an accomplishment of the Marshall Plan and the economic miracle that saw West Germany rise again from the ashes of its ruin. A few blocks from city hall, we went to see Mom’s first home at Poststrasse 6, and Dad and Gary waited in our rented van while Mom and I went closer to inspect it. She pointed out her bedroom window, the garden where she had played with Trudi, the Hotel Minerva at the corner (which now looked vacant, out of business), and Sigmar’s former office across the street. An

EISEN GLATT

sign outside a glistening showroom of whirlpool tubs encased in marble provided our first evidence that the Glatts continued to run the construction and plumbing supply company that they had taken over from Sigmar and his brother when it was “Aryanized” in 1938.

“Oh, how I wish I could see the inside of my old home one more time!” Mom murmured wistfully, which propelled me to the wide oak door and a directory of residents. The imposing house where she was born, converted in the war to expand the Hotel Minerva, had evidently since been turned into apartments, and over her protestations that it would be improper to intrude on strangers, I rang a random bell. A buzzer answered, granting access, and Mom came trailing behind me, virtually on tiptoes, peering past my shoulder as I began to climb the winding stairs. On the second floor, the resident who’d admitted us directed us to the landlord. But when we reached that door, the frail blond woman who opened it a crack assumed that I had come to see her son and pointed up another flight. Rosemarie Stock, formerly Schöpperle, failed to notice Mom, nor did Mother recognize her childhood playmate from the hotel next door. On the top floor, a tall young man with sandy hair responded to my knock, an animated smile lighting up his handsome, open features. I expected Mom to explain to him in German the reason for our coming to his doorstep, but she stood shy and mute behind me.

“We’re visiting from the United States,” I tried in halting German to cover for her silence. “My mother’s family owned this house before the war, and she is very eager to have a look inside, if you don’t mind. It’s her first time back, and it would mean a lot to her.”

“

Natürlich!

” Of course! he cried, greeting Mom with the cheery enthusiasm of someone who had spent a good part of his life eagerly awaiting her arrival. Oddly, it seemed that we were keeping to a long-arranged appointment. “Frau Günzburger!” he suddenly burst out, surprising us by using her maiden name, which I knew I hadn’t mentioned. He grasped Mom by the arm and drew her into his apartment. “I’ve waited so long to meet you. I can’t believe you’re really here!” he said. “I’ve always wanted to know the truth about what happened. I questioned how we got this house, if your family was treated fairly.…”

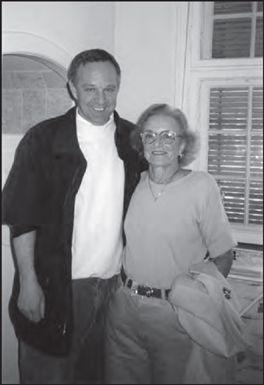

Michael Stock warmly welcomes Janine to her girlhood home at Poststrasse 6

.

(photo credit 23.1)

Michael Stock, thirty-six years old, exuding warmth and curiosity, insisted we sit down as he rushed to a cabinet for a brandy bottle and three glasses. “A special occasion requires a toast!” he exclaimed, relieving Mom’s discomfort with such jovial hospitality that, freely pouring brandy into her glass, he let it overflow the rim. Brandy ran across the table in a wasted puddle, and he broke out laughing. The accidental spill appeared to dramatize that the fullness of his welcome surpassed the limits of the possible.

Then, and in greater detail later on that evening when we invited Michael and his girlfriend, Karla, out to dinner, Mom listened in amazement as he related what had happened on the Poststrasse since her escape. He explained that in 1938, his grandfather, August Schöpperle, had promptly launched the renovation of Sigmar’s home as an extension of the hotel, but found himself overwhelmed by debt before the work was finished. Within a year, riddled by anxiety that the war would cut off local tourism—never imagining that it would actually boost business as the government rented rooms for families whose homes were bombed—his grandfather hanged himself. August’s widow succumbed to alcohol, and management of the Minerva fell to their daughter Rosemarie, then nineteen and unprepared for so much responsibility. No surprise, perhaps, that four days after her father’s funeral she met the man she shortly married—Friedrich Alois Stock, an athlete in the 1936 Berlin Olympics who had the strapping good looks of Johnny Weissmuller and was twenty years her senior. By profession a chemist with Schering, in 1941 he was off to war, assigned to duty until the end at a chemical lab, presumably in Poland. Michael said Friedrich would not discuss it, but he suspected that his father had helped produce deadly chemicals of war, including components of the Zyklon B used in Nazi killing chambers. After his return, the family continued operating the hotel until the mid-1970s, and in 1986, eight years after Friedrich’s death, Rosemarie sold it—or at least the building at Poststrasse 8 that had housed it from the start. It was then, Michael added, that they moved next door to the Günzburgers’ former home at Poststrasse 6, which they had kept, and had it reconfigured into five apartments.

Michael proceeded to show us all around the building, from his newly renovated home in the peaked-roof attic (where Mom remembered the birdlike Fräulein Ellenbogen living), to his bright, contemporary office in the once-dark basement (where Mom recalled their cook storing bins of vegetables), to tenants’ flats on other floors. At last, Michael led us to his mother’s place.

“I’m glad to see that you survived,” Frau Stock told Mom. She invited us to sit and talk, but her tone was emotionless and clipped, her eyes alert and darting nervously. Despite a cough so deep and hacking it disrupted conversation, she smoked incessantly. Her words lined up like pointed pickets on a verbal fence around the property, in case it should turn out that Mom’s impromptu reappearance on the Poststrasse after more than fifty years was sparked by some financial motive. She seemingly suspected that we had come to Freiburg expressly to reclaim the house that Sigmar had been forced to sell her father at a price far below its worth. Michael put its value in 1989 at over $3 million.

“You must have lived very well in the United States on the money my father paid for the house,” Frau Stock proposed, dragging on a cigarette that induced another fit of coughing spasms.

But Mom herself was drifting in memories that overlaid this unforeseen experience in her childhood home like a film of dust, and Frau Stock’s probing caught her unawares. “What money?” she retorted, sitting up sharply, stiff with concentrated effort to remain as polite in this uneasy interchange as Alice would have hoped of her. “What do you mean?” Mom asked, knowing Sigmar had relinquished every bit of it to the coffers of the Reich. “Live

well

on the money we got for the house? We were forced to leave with nothing.”

“If that is so, then why did

we

have to pay anything?” Frau Stock persisted, querulous and deaf to the resentment infiltrating Mother’s voice. “It was hard on my father. Why didn’t your father just

give

him the house before you left if you couldn’t take the money anyway?”

“Why don’t you go and ask the Führer?” Mom snapped, jumping from her chair to end the inquisition. “Whatever sum your father paid to mine, the Nazis grabbed it all.”

The following year, meeting with Frau Stock again when I returned to Freiburg for a follow-up research trip, we would sit together side by side in what had been my grandparents’ salon over coffee and a sumptuous array of pastry. In 1952, she would tell me, after Norbert had come to see them and cordially discussed the matter, she and her husband agreed to pay 15,000 Deutsche Mark (then worth less than $4,000) in restitution. She wanted us to know that. She added that in 1980, to satisfy a lien on the property in the name of Edmond Cahen that dated back to 1938, she had also sent

him

the equivalent of $5,000. At the point when the Reich was confiscating Jewish assets, I realized, Sigmar’s nephew had probably purchased an interest in the building, holding safe his payment for Sigmar in expectation of the family’s penniless arrival in Mulhouse a few months later.