Crete: The Battle and the Resistance (15 page)

Read Crete: The Battle and the Resistance Online

Authors: Antony Beevor

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #War, #History

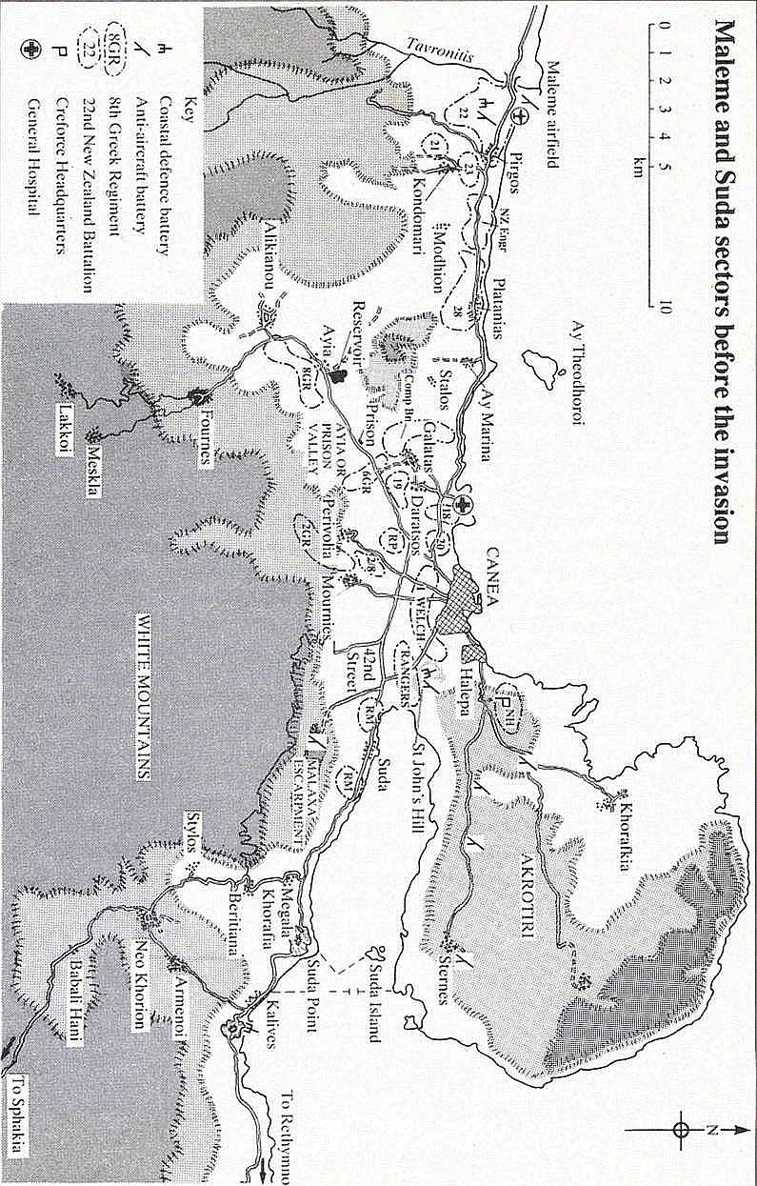

At Rethymno there were two Australian battalions and two Greek battalions guarding the airfield, and in the town a very effective force of Cretan gendarmes who were properly armed. Two main groups of reserves were organized: another two Australian battalions with most of the motor transport at Georgioupolis, between Suda and Rethymno, and the 4th New Zealand Brigade as well as the 1st Battalion of the Welch Regiment close to Canea and Creforce Headquarters.*

* From west to east by road, the distance from Maleme to Canea was 18 kilometres, Canea to Suda 6 kilometres, Suda to Georgioupolis 31 kilometres, Georgioupolis to Rethymno 36 kilometres and Rethymno to Heraklion 75 kilometres.

Along the crucial sector between Canea and Maleme, the New Zealand Division was deployed to defend the coast as well as the airfield and the valley. This allowed little depth to their defences. And the divisional reserve, 20th Battalion, was held close to Canea and the main force reserve rather than near Maleme.

Freyberg had jumped to the conclusion that he faced 'a seaborne landing bringing tanks', yet he ordered no study of likely beaches. A rapid examination of naval charts would have shown that in the Suda, Akrotiri, Canea and Maleme sectors, only the beach from Maleme to Platanias could have been considered possible for a landing in any strength, and then only if the Germans had assault ships and landing craft, which they did not.**

** I am most grateful to Lieutenant Colonel J. Pumphrey (late Northumberland Hussars) who walked the length of the coast just before the invasion, and to Captain R.G. Evans RN in Athens for obtaining and analysing the relevant charts

A number of regimental officers noticed this flaw in their orders.

The Welch Regiment, which had been based on that stretch of coast since February, considered an

'invasion by sea' a 'somewhat unlikely possibility'. But the only senior officer in the New Zealand Division to spot it was Colonel Howard Kippenberger, commanding the improvised 10th Brigade to the west of Canea, and he did not raise the question at the time: he just reduced his troops watching seawards.

Most astonishing of all, Freyberg's extended line of defence came to a halt on the far edge of Maleme airfield, which General Wavell and intelligence reports had identified from the beginning as one of the enemy's principal objectives. Brigadier Tidbury had pointed out over five months before, on 25

November, that the site of this airfield had been badly chosen because it was acutely vulnerable to attack. Brigadier Puttick, who had taken Freyberg's place as divisional commander, soon became conscious of the threat to his flank. He asked for reinforcements to cover the river-bed of the Tavronitis on the west side of the airfield, since it offered an ideal assembly area for enemy paratroops.

Creforce Headquarters apparently applied for permission from the Greek authorities to move the 1st Greek Regiment from Kastelli Kissamou, but only received agreement on 13 May. (This seems strange since Freyberg had already been given full command of all Greek forces.) Freyberg then said that the airborne attack was imminent, so there would not be time for them to march to the Tavronitis and dig trenches. In fact he most probably thwarted this move in the belief that it might betray 'most secret sources', a perhaps exaggerated fear since he already had one battalion round the airfield and two on the eastern side.

Freyberg spent little time studying the ground at Maleme. Colonel Jasper Blunt urged him to move more troops there, but Freyberg refused, either to safeguard the secret source of their intelligence, or because he did not want to diminish his coastal defences. In any case, he considered Heraklion a more important objective for the enemy, and he lacked confidence in the abilities of the commander there, Brigadier Chappel of the 14th Infantry Brigade. His reconnaissances were also limited 'owing to policy matters holding me at HQ'.

One distraction was the question of whether the King should remain on Crete or leave before the German invasion began. Wavell, the Foreign Office and the War Cabinet in London believed he should stay as an example to neutral countries. General Heywood, on the other hand, argued that the indignity and danger of having to run away the moment the enemy landed should be avoided by his immediate withdrawal to Egypt. The King seems to have had little say in his own fate.

Freyberg was understandably dubious at the idea of the King remaining on the island, since defending a group of civilians against parachutists was the most uncertain calculation of all. He felt that they were far too exposed out at Platanias, where they were staying in an old Venetian country house called Bella Kapina (a corruption of Bella Campagna), and invited them to move within the perimeter of Creforce Headquarters. But during their visit on 17 May to the building earmarked for them, a heavy air raid forced the King and his companions to take cover in slit trenches. King George decided to refuse the accommodation offered. Two days later, on the eve of the invasion, he moved instead with his entourage to another house near Perivolia, closer to the foothills of the White Mountains over which they would have to escape.

Freyberg's responsibility for all the Greek forces on the island included feeding and arming them.

Weapons were handed out in a random manner from the Greek army headquarters in Canea —

Steyers, Mausers, Mannlichers, Lee Enfields and a few antiquated St Etienne machine guns; a handful of cartridges, often of the wrong calibre, was pushed across at the same time. Few men received more than three rounds apiece.

Freyberg did not share the prejudices of some of his officers who deprecated the worth of these Greek units, mostly withdrawn from the mainland and supplemented by ill-trained recruits. Kippenberger described those attached to his brigade as 'malaria-ridden little chaps from Macedonia with four weeks' service'. Freyberg appointed Colonel Guy Salisbury-Jones from the Military Mission in Greece to take over the task of organization and liaison. Eight Greek regiments were formed from 9,000 men. Some of their battalions collapsed at the shock of battle, either due to poor leadership, or because their training and armament were inadequate to face determined attacks by German paratroop forces. But others astonished their detractors by their staunchness. In a fierce defence towards the end of the battle the 8th Greek Regiment, strengthened with Cretan guerrillas, saved the Commonwealth forces from envelopment at the most critical stage of their retreat.

It is greatly to Freyberg's credit that he quickly recognized how 'the entire population of Crete desired to fight'. Some British officers clung to the presumption that their regular troops would still perform better in an irregular battle than Cretans fighting in defence of their native land with an unbeatable knowledge of the ground and generations of guerrilla warfare behind them. Their least forgivable disservice to the Cretans was their failure to give volunteers some form of uniform and thus afford them an official status to protect them from being shot on capture as

francs-tireurs.

Even if they thought there were no weapons to hand out — in Canea, 400 Lee Enfield rifles remained locked up in the ancient Venetian galley sheds beside the harbour — the idea of handing over captured enemy weapons does not seem to have occurred to many officers until they saw what the Cretans could achieve with the crudest of weapons and virtually suicidal bravery.

Freyberg's lack of confidence in Brigadier Chappel at Heraklion has never been satisfactorily explained. Chappel, a regular officer from the Welch Regiment of great experience, may not have been a very charismatic figure but he was by no means inferior to most of his New Zealand counterparts.

Distance, shortage of transport and the bad condition of the coast road between Heraklion and Canea made Chappel's command there virtually independent. Installed in a quarry, like Creforce itself, 14th Infantry Brigade's headquarters personnel were drawn mostly from the Black Watch which provided the defence platoon, the brigade major, Richard Fleming, and Lieutenant Gordon Hope-Morley, one of the two intelligence officers.

The other intelligence officer was Patrick Leigh Fermor, who spoke Greek as well as German. After his semi-piratical adventures on the island of Antikithera, Leigh Fermor had reached Kastelli Kissamou. Soon afterwards, he met up with Prince Peter of Greece and Michael Forrester, his fellow member of the British Military Mission. The three of them spent several days based at Prince Peter's house on the coast north of Galatas. Then, when Leigh Fermor continued eastwards to Heraklion, Forrester acted as Colonel Salisbury-Jones's liaison officer, checking on the needs of the Greek regiments. The two men met up for dinner in Heraklion on the night of 18 May when Forrester visited the two Greek regiments grouped within and without the town's huge stone ramparts.

Another brief visitor to the British headquarters at Heraklion was John Pendlebury, still in search of spare weapons for the guerrilla kapitans. Leigh Fermor described how his 'handsome face, his single sparkling eye, his slung guerrilla's rifle and bandolier and his famous swordstick brought a stimulating flash of romance and fun into that khaki gloom'.

Even the sceptics among the regular officers of the 14th Infantry Brigade soon came to realize the fighting potential of 'Pendlebury's thugs'. There were three principal guerrilla kapitans with whom he worked in the region of Heraklion — Manoli Bandouvas, a rich patriarchal peasant of great influence who had moustaches like the horns of a water buffalo; Petrakageorgis, the owner of an olive-oil pressing business, lean-faced with deep-set eyes and a fearsome beak of a nose; and the white-haired Grigorias Antonakis, better known as Satanas, the greatest kapitan of them all.

'Satanas', wrote Monty Woodhouse, 'owed his name to the general belief that nobody but the devil himself could have survived the number of bullets he had in him.' But according to another version, this name dated from the day of his christening. The priest apparently was just saying 'I baptize thee', when the baby seized his beard, causing him to exclaim: 'You little devil!' Another of Satanas's distinguishing features was a mutilated hand. Furious with himself at losing heavily at dice, having promised to play no more, he had shot off his rolling finger. In the heat of the moment he forgot that the offending object was also his trigger finger.

The subject of Pendlebury's last days still attracts enormous interest. Many plans were discussed and he seems to have been in constant movement, although always coming back to Heraklion. He sent Jack Hamson with a hundred Cretan volunteers up to the Plain of Nida on the eastern flank of Mount Ida in case German paratroops dropped there, and with Herculean efforts they shifted boulders down on to its smooth areas to prevent aircraft landing.

Mike Cumberlege was asked to take his armed caique HMS

Dolphin

round to Hierapetra to see if a cargo of weapons and ammunition could be salvaged from a ship sunk in the harbour there. He found a sponge-diver from the east coast of the island, and arranged his temporary release from the Greek army. On the eve of their departure, Pendlebury gave a dinner at the officers' club overlooking the harbour of Heraklion. Ignoring the club's protocol of rank, he insisted that their crewman, Able Seaman Saunders, should also come. Over the meal, which consisted of fish concussed by German bombs that morning, they discussed a raid against the Italian-occupied island of Kasos for the night of 20 May, after the

Dolphin

returned. Cumberlege and his crew would ferry Pendlebury and his Cretans over to seize a few prisoners for interrogation. These guerrillas, known in Greece as

andartes,

were a fearsome bunch. Hammond recalled how they 'breathed blood and slaughter and garlic in the best Cretan style'.

If the Germans overran Crete, Pendlebury was determined to stay behind to organize guerrilla warfare.

He regarded himself as virtually a Cretan. Life for him at this time consisted of secret arms dumps, guerrilla groups, sites for ambushes and demolition targets. His pet project — a far-sighted one as events proved — was to convince the 14th Infantry Brigade of the need for snipers to cover springs and wells. Water was the first vital commodity the paratroopers would need to replenish. But it does not seem that the British followed his advice. For Cumberlege and Hammond, that evening at the officers' club was their last sight of Pendlebury. They left on the

Dolphin

for Hierapetra the next morning.

In the last few days before the German invasion, Freyberg proved a perfect figurehead: his tours of inspection shortly before the battle were really an exercise in morale-boosting. He exuded a burly confidence, and his reputation for bravery gave him presence in the eyes of his soldiers, who referred to him with affectionate admiration as 'Tiny'. With his rasping voice, he told them, 'Just fix bayonets and go at them as hard as you can.'

But some officers suspected that his stirring words were not borne out in the Creforce operation order.

Several inconsistencies made them uneasy. Freyberg himself had also advised troops 'not to rush out when the paratroops come down', and he had placed much emphasis on barbed wire as a defence. As most junior commanders and soldiers instinctively recognized, the only way to deal with an airborne assault was to counter-attack immediately. Much had also been made of the force reserves in the operational order, yet their deployment at the right time depended on several elements: accurate information; good communications; proximity to the objective; motor transport, of which there was very little; and the ability to move to the threatened sector without unnecessary exposure to air attack.