Courtiers: The Secret History of the Georgian Court (27 page)

Read Courtiers: The Secret History of the Georgian Court Online

Authors: Lucy Worsley

Tags: #England, #History, #Royalty

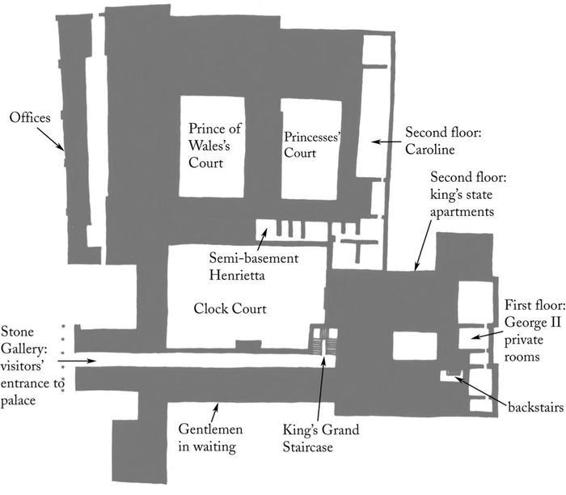

Then Mrs Keen moved on through the state and private apartments of the king and queen. Henrietta’s large, if damp, apartment (five chimneys) was in Clock Court, and it was separated from the King’s Privy Lodgings (twenty chimneys) only by the wardrobe, a storage room for unused furniture.

George II’s private apartments lay on the first floor, with a lovely outlook east over the gardens. Caroline, on the other hand,

was lodged in a rather poky suite with no views. The ladies in ‘close waiting’ at any given time spent their night right outside Caroline’s bedchamber, upon a bedstead with a feather mattress and ‘five fine blankets’.

86

When the king wanted to sleep with his wife, he always came to her rooms rather than vice versa.

The scene of the action: the king’s, the queen’s and the mistress’s apartments at Kensington Palace

When the family was in residence and all 246 fireplaces were lit, the building was toasty warm: ‘in all ye rooms great coal fires instead of wood’.

87

Fortunately the palace was by now well protected from fire, a constant concern both at Kensington and elsewhere in the wooden world of eighteenth-century London. The palace had been terribly damaged in 1692, when a blaze caused by ‘the carelessness of a candle’ destroyed part of the south-west range. On that occasion the fire engines were so slow to arrive from Whitehall that the flames were eventually extinguished by soldiers

bringing up and breaking open bottles of beer from the cellars.

88

By 1734, Kensington Palace had its own fire engines.

89

These devices were tanks of water on wheels, and their crews pumped huge levers to create a flame-quenching jet. John Rowley, formerly master of mechanics to George I, had designed the fire engines at Kensington, Hampton Court and the House of Commons. His masterpiece was the ‘great water engine’ at Windsor Castle, which remained in working order for forty years.

90

*

The accounts for the month of August 1734 show the prodigious quantity and variety of food that Henrietta and her fellow courtiers consumed. It was prepared in specialised departments round the Kitchen Court ranging from the ‘Jelly Office’ to the ‘Herb Office’, while outside on the green were the ‘Feeding Houses for Fowls’.

91

Many of the employees of these various ‘offices’ lived in garrets immediately above their place of work.

A cook, sketched by William Kent

The chosen suppliers of goods to the kitchens would provide produce on credit at agreed rates, and everything was carefully recorded by the clerks. Volume after volume of their work remains in the National Archives today: the ‘credit accounts’ listing all the food entering the Georgian kitchens, and the ‘diet books’ registering every single dish cooked and served to the royal family. The more exotic provisions to appear include olives, gherkins and

mangoes; Bologna sausages and giblet pies; and udders, trotters and pig’s heads.

92

The courtiers were entitled to various allowances of food depending upon their rank. The more senior, like Molly Hervey, had ‘three pats of Richmond butter and a quarter-pint of cream’ every day by right.

93

Even the lowly sempstress, Mrs Purcell, enjoyed a daily bottle of claret.

94

Despite the emphasis placed upon meat as food fit for kings, there was no shortage of vegetables available too. In two years, for example, the royal gardens provided

1684 salads. Above 6000 cabbage lettuces. 3541 cucumbers. 1088 artichokes. 4668 celery and endive. 1351 bundles of asparagus with radishes, peas, beans, French beans, carrots, savoys, cauliflowers, onions, sweet herbs, borecole [broccoli?] and great parcels of flowers.

This was as well as ‘4368 baskets of fruit of all sorts’.

95

Caroline was fond of fruit with sour cream in the mornings, and enjoyed ‘a fine breakfast with the addition of cherries & strawberry’.

96

Drinking was another important part of life at Henrietta’s court. Hot chocolate was taken each morning. Later in the day tea soothed many a courtier’s cares: a lover lost, a gambling debt gained. It was promoted by matrons as a cure for a broken heart: ‘now leave complaining, and begin your

Tea

’.

97

But John Hervey’s father thought it was ‘detestable, fatal liquor’, which had brought many people ‘near to death’s door’.

98

Although tea was considered rather decadent, meals were always accompanied by something even stronger. Each day after dinner, we hear, the ‘men remain at the table; upon which, the cloth being taken off, the footmen place a bottle of wine’. The servants present the drinkers ‘with glasses well rinsed’ and they ‘always drink too much, because they sit too long at it’.

99

Lord Lifford on one occasion drank so much that he fell off his chair, and the next morning Caroline ‘railed at him before all the Court upon getting drunk in her company’.

100

Peter Wentworth found that this post-prandial ritual between

three and five every day placed a sore strain upon his resolution to avoid taking even a single ‘drop of wine too much’. His seventeen-year-old daughter Catherina’s sudden and tragic death from consumption, the ‘folly & extravagance’ of his son George and anger at a villainous son-in-law who’d contracted syphilis still gave him the odd ‘occasion to drown and stupifie [his] thoughts’.

101

The year 1734 was one of panic about a new drinking craze among London’s poor. Caroline, among others, was stridently in favour of Parliament’s legislating against ‘Mother Gin’, or ‘Madam Geneva’ as it was also known. This strong and novel spirit was drunk by the pint, like beer, with devastating consequences, and was causing chaos in London. The streets were lined with the insensible bodies of the inebriated, while those still conscious showed the ‘utmost rage of resentment, violence of rudeness, and scurrility of tongue’.

102

The lists of fatalities recorded in the newspapers began to include ‘excessive drinking of Geneva’ alongside the more familiar ‘drowned accidentally in the river of Thames’.

103

Just two years later the draconian Gin Act was introduced, which sought – with limited success – to have gin sold only through recognised and licensed outlets.

While the rich condemned the poor for the miserable manner of their escape from the urban grind, Lord Chesterfield nevertheless considered drinking deeply to be ‘a necessary qualification for a fine gentleman’.

104

The Maids of Honour likewise refused to stint themselves. They could order as many bottles of wine as they liked to drink with their dinner (although the under-butlers always inflated the total in the official record and drank the difference themselves).

105

But Lord Chesterfield also warned his son to avoid becoming ‘flustered and heated with wine: it might engage you in scrapes and frolics, which the King (who is a very sober man himself) detests’.

106

*

Princesses like Caroline, sent to spend their married lives in foreign countries, inevitably missed their native food. The German-born Duchess of Orléans longed for German sausages in Paris.

She proudly claimed to have made smoked ham fashionable in France, along with ‘sweet-and-sour cabbage, salad with

Speck

, red cabbage and venison’.

107

George II likewise loved his German dishes. One Mr Weston, he announced, must have the job of ‘first cook, for he makes most excellent Rhenish soup’.

108

But their Germanic fondness for Rhineland soup and sausages caused the Hanoverians much trouble and unpleasantness. Propaganda released by the Pretender, the so-called James III, claimed that he ate only English dishes such as roast beef and Devonshire pie, and drank only English beer.

109

Unlike the king, some other foreigners were surprisingly enthusiastic about English cooking. Baron Pöllnitz, a Pole visiting London, wrote that ‘there is excellent beef here; and I am in love with their puddings’.

110

‘Ah, what an excellent thing is an

English pudding

!’ sighed a French visitor.

‘To come in pudding-time

’ means ‘to come in the most lucky moment in the world’.

111

The royal family’s food reached their mouths via a lengthy chain of servants in which Henrietta was intimately involved. Unlike his reclusive father, George II was regularly willing to dine before spectators. This curious spectacle was almost like feeding time at a royal zoo, and left the watching crowds ‘mightily pleas’d’ with the show.

112

Public dining for George II, Caroline and their children took place every Sunday, when their table was ‘plac’d in the midst of a hall, surrounded with benches to the very ceiling, which are fill’d with an infinite number’ of viewers.

113

Usually ‘the room was so throng’d with spectators there was no stirring’.

114

The audience were mere members of the public who’d queued for admission. At one dinner attended by Sir John Evelyn, he found them rather coarse: ‘very dirty and noisy’.

115

George II and Caroline’s personal servants found the pressure of the performance and of keeping the food flowing in a suitably respectful manner to be quite considerable. It was ‘a very terrible fatigue’ to the Lady of the Bedchamber whose duties included taking the covers off the dishes, carving the meat, kneeling down

to taste the food for poison and, besides all that, ‘giving the Queen drink’.

116

Such a summer dinner served to Caroline in June 1735 consisted of a lengthy procession of beef, chicken and mushrooms, mutton hashed in a loaf, veal and sweetbreads fried, pullets and cream, a haunch of venison, cold chicken and pickles, peas and cucumber, a lobster, gooseberry and apricot tart, smoked salmon and prawns.

117

Henrietta’s role, as Bedchamber Woman, was to form a link in the human chain that kept the Lady of the Bedchamber supplied with utensils. When Caroline wanted a drink, a page handed a glass to Henrietta, who gave it to the Lady, who finally presented it to the queen.

118

All this etiquette meant that any grand dinner was fraught with potential insult. It was the host who determined whether his guests would be served on bended knee or not, and guests felt slighted if ceremonies were omitted. Caroline’s daughters the three elder princesses once refused to stir from the antechamber before a dinner until ‘the stools were taken away’ and proper chairs carried in, and after the meal they ‘were forced to go without their coffee’ for fear that ‘they might have met with some disgrace … in the manner of giving it’.